Wine and Art is an ongoing GFR series on the relationship between the two creative endeavours by working artist and author Lorette C. Luzajic.  For the first few days of my annual New Year’s Resolution diet, I could think of nothing but food and wine. My life was flashing before my eyes, a lifetime of gorgeous concoctions and libations. Visions of sugar plums danced in my head, and rivers of spicy shiraz. As I subsisted on hardboiled eggs, paprika, chopped celery, and the like, my mind devised strategies to survive the temporary deprivation. Maybe I could just look at food! It was a greedy buffet, my long table set with stacks of art books. From Renoir’s irritating outdoor lunchtime gaiety to uncouth 16th century peasantry, I watched people eat. I looked at dozens of those lobster claw and lemon still lifes, and contemporary ultra realist candy wrappers and fried eggs. There were the requisite ancient carcass paintings of rabbits and pheasants, and the ones of contemplative and sexy women with wine. And bowl after bowl of apples. Food, glorious food! Food has played a long and important role in art history. It has served as a profound symbolic language that can be read at museums around the world, illuminating our past and our imagination. The things that make food important – nourishment, family time, festivities, funerary goodbyes, occasions of sacrament and celebration, courting and seduction, sustenance and work- are precisely what has made it an important subject for artists. I’m intrigued by the exquisite, detail-obsessed still lifes that are four or five centuries old. They seem so dusty and stodgy these days, merely quaint relics among more hip exhibits about Bowie or microaggressions. Myself being partial to sardonic, frenetic gestures of colour or collage, I’m guilty of thinking “you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all.” But now I was lured in by oysters and chalices of tepid amber and half-peeled lemons.

For the first few days of my annual New Year’s Resolution diet, I could think of nothing but food and wine. My life was flashing before my eyes, a lifetime of gorgeous concoctions and libations. Visions of sugar plums danced in my head, and rivers of spicy shiraz. As I subsisted on hardboiled eggs, paprika, chopped celery, and the like, my mind devised strategies to survive the temporary deprivation. Maybe I could just look at food! It was a greedy buffet, my long table set with stacks of art books. From Renoir’s irritating outdoor lunchtime gaiety to uncouth 16th century peasantry, I watched people eat. I looked at dozens of those lobster claw and lemon still lifes, and contemporary ultra realist candy wrappers and fried eggs. There were the requisite ancient carcass paintings of rabbits and pheasants, and the ones of contemplative and sexy women with wine. And bowl after bowl of apples. Food, glorious food! Food has played a long and important role in art history. It has served as a profound symbolic language that can be read at museums around the world, illuminating our past and our imagination. The things that make food important – nourishment, family time, festivities, funerary goodbyes, occasions of sacrament and celebration, courting and seduction, sustenance and work- are precisely what has made it an important subject for artists. I’m intrigued by the exquisite, detail-obsessed still lifes that are four or five centuries old. They seem so dusty and stodgy these days, merely quaint relics among more hip exhibits about Bowie or microaggressions. Myself being partial to sardonic, frenetic gestures of colour or collage, I’m guilty of thinking “you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all.” But now I was lured in by oysters and chalices of tepid amber and half-peeled lemons.  As it turns out, upon careful contemplation, there is considerable variety in the European post-Reformation still life genre. Flowers became an enormously popular subject matter, for example, but food spawned a host of subgenres, including the “ostentatious still life” genre, the “vanitas” genre, and “breakfast paintings” like Claesz Van Dijck’s “Still Life With Cheese.” The proliferation of food and flower art was a natural outcome of the Reformation, when art depicting religious figures was declared idolatry. Subject matter turned from the divine toward the everyday. At the same time, the patronage of art was shifting from the Catholic Church to ordinary citizens of means. Painting began to reflect the world of actual people rather than Biblical or mythological narratives. Part of the purpose of food portraits was, of course, a declaration of status. More people could afford to eat more kinds of food more often; and if you couldn’t always afford sumptuous banquets, you pretended you did by showing foodstuffs off on your walls. The paintings reflected the ever-opening markets of the region, with exotic fruits and spices that were new to the table. Being blessed with these new luxuries wasn’t something you kept secret. But in the dour days of Dutch reform, the depiction of beauty for its own sake was frowned upon. As with the paintings of gamblers and tavern dwellers, art purported to act as moral instruction. The upper crust underhandedly flaunted their upwardly mobile position in society, but the paintings were technically warnings about excess, greed, sloth, and gluttony.

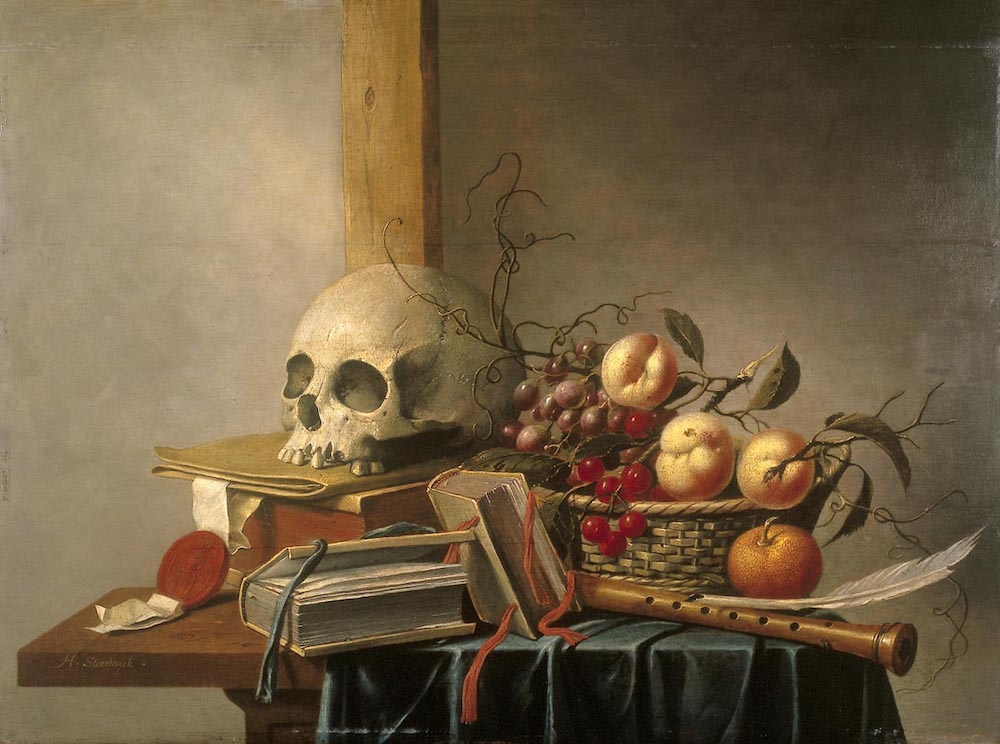

As it turns out, upon careful contemplation, there is considerable variety in the European post-Reformation still life genre. Flowers became an enormously popular subject matter, for example, but food spawned a host of subgenres, including the “ostentatious still life” genre, the “vanitas” genre, and “breakfast paintings” like Claesz Van Dijck’s “Still Life With Cheese.” The proliferation of food and flower art was a natural outcome of the Reformation, when art depicting religious figures was declared idolatry. Subject matter turned from the divine toward the everyday. At the same time, the patronage of art was shifting from the Catholic Church to ordinary citizens of means. Painting began to reflect the world of actual people rather than Biblical or mythological narratives. Part of the purpose of food portraits was, of course, a declaration of status. More people could afford to eat more kinds of food more often; and if you couldn’t always afford sumptuous banquets, you pretended you did by showing foodstuffs off on your walls. The paintings reflected the ever-opening markets of the region, with exotic fruits and spices that were new to the table. Being blessed with these new luxuries wasn’t something you kept secret. But in the dour days of Dutch reform, the depiction of beauty for its own sake was frowned upon. As with the paintings of gamblers and tavern dwellers, art purported to act as moral instruction. The upper crust underhandedly flaunted their upwardly mobile position in society, but the paintings were technically warnings about excess, greed, sloth, and gluttony.  The food and flowers all represented the temporary world, fleeting sources of sustenance that would decay or disappear in time. If you’ve ever wondered why this era produced so many pictures of fruit or crustaceans surrounded by skulls, timepieces, candles, tobacco, violins, etc, now you know. These were lessons in impermanence, gratitude, and moderation: reminders that the pleasures of life would pass away. (Many vanitas still lifes used object arrangements without food, and all those paintings that show dreamy looking people sitting around with a skull and candle were portraying the same theme.)

The food and flowers all represented the temporary world, fleeting sources of sustenance that would decay or disappear in time. If you’ve ever wondered why this era produced so many pictures of fruit or crustaceans surrounded by skulls, timepieces, candles, tobacco, violins, etc, now you know. These were lessons in impermanence, gratitude, and moderation: reminders that the pleasures of life would pass away. (Many vanitas still lifes used object arrangements without food, and all those paintings that show dreamy looking people sitting around with a skull and candle were portraying the same theme.)  Perhaps the very popularity of the still life is what drove it into inconsequence. By the time modern art rolled around, it was the lowliest genre. The ubiquitous fruit bowl was emptied of all its rich symbolism (temptation, innocence, scarcity, the Eucharist, etc.) Paul Cezanne’s interest in the subject was not in hidden meanings, but about the usefulness of shapes. Foreshadowing cubism and abstraction, he reduced all of his content to its geometric essential: cones, cubes, and spheres. Cezanne’s outrageous flouting of the rules would later be recognized as deconstructing how we see. But at the time, the fruit bowl had long become a decorative cliché.

Perhaps the very popularity of the still life is what drove it into inconsequence. By the time modern art rolled around, it was the lowliest genre. The ubiquitous fruit bowl was emptied of all its rich symbolism (temptation, innocence, scarcity, the Eucharist, etc.) Paul Cezanne’s interest in the subject was not in hidden meanings, but about the usefulness of shapes. Foreshadowing cubism and abstraction, he reduced all of his content to its geometric essential: cones, cubes, and spheres. Cezanne’s outrageous flouting of the rules would later be recognized as deconstructing how we see. But at the time, the fruit bowl had long become a decorative cliché.  Still, food in art remained popular among the unwashed masses, even if the elite tastemakers found it déclassé. Now, it has become one of the most important themes among hyperrealist painters. With today’s fine art world saturated by installation, digital production, and performance art, not to mention excrement in tin cans and diced up taxidermy, there is an ongoing resistance of painters who insist on, well, paint, as well as on the development of technical skills in draftsmanship and mastery of their medium. One mainstay of hyperrealists is food. And in today’s global marketplace, there is no limit to the cornucopia of colours, shapes, and textures available for them to portray.

Still, food in art remained popular among the unwashed masses, even if the elite tastemakers found it déclassé. Now, it has become one of the most important themes among hyperrealist painters. With today’s fine art world saturated by installation, digital production, and performance art, not to mention excrement in tin cans and diced up taxidermy, there is an ongoing resistance of painters who insist on, well, paint, as well as on the development of technical skills in draftsmanship and mastery of their medium. One mainstay of hyperrealists is food. And in today’s global marketplace, there is no limit to the cornucopia of colours, shapes, and textures available for them to portray.  From bags of oranges that are serious studies of light, to the playful paeans to soda or ketchup, these magicians create work that somehow appears more real than photography. The succulent grease that drips from the edge of a hamburger just might stain your sofa. Jason Walker’s famous donut paintings are even better than the real thing, a perfectly satisfying substitute for the sweet-tooth I’m not feeding right now. The subject of food in art is, if you’ll indulge me, a feast for the eyes. And I’ve only offered a taste- discover its delicious history for yourself.

From bags of oranges that are serious studies of light, to the playful paeans to soda or ketchup, these magicians create work that somehow appears more real than photography. The succulent grease that drips from the edge of a hamburger just might stain your sofa. Jason Walker’s famous donut paintings are even better than the real thing, a perfectly satisfying substitute for the sweet-tooth I’m not feeding right now. The subject of food in art is, if you’ll indulge me, a feast for the eyes. And I’ve only offered a taste- discover its delicious history for yourself.  Lorette C. Luzajic is an artist and writer with roots in southern Ontario’s wine country soil. Native to Niagara, at home in Toronto, her work is inspired by wine, cheese, and bleak post-apocalyptic literature. Visit her at mixedupmedia.ca. Photo: Ralph Martin.

Lorette C. Luzajic is an artist and writer with roots in southern Ontario’s wine country soil. Native to Niagara, at home in Toronto, her work is inspired by wine, cheese, and bleak post-apocalyptic literature. Visit her at mixedupmedia.ca. Photo: Ralph Martin.

Feast For The Eyes – Food in Art