This month I sat down for lunch with the Consejo Regulador of Rioja and a handful of wine writers at TOCA. The lunch was held to promote 2016 as the inaugural year of DOCa Rioja’s campaign for the national Canadian market. TOCA’s Executive Chef Jitin Gaba and Head Sommelier Lorie O’Sullivan were on hand to describe the wines and dishes to us.

Present were Mr. Jose Luis La Puente, Managing Director; Mr. Ricardo Aguiriano, Global Marketing Director; Ms. Ana Fabiano, Trade Director North America; and Ms. Dhane Chesson, Director National Accounts North America.

At almost 3% of total exports, Canada is becoming an important market for Rioja. That number may seem small and we may not drink as much of the stuff as the Brits, Germans, or Americans, but more and more Canadians are drinking Rioja, up 23% from 2014, while growth in the US and more traditional Rioja markets is slowing. In 2011, we were 11th in terms of export; now, Canada is 7th.

What is driving this surge and how do Canadian wine drinkers see Rioja?

The first question is trickier and I’ll give my thoughts later. As for the latter, I contend that for the average Canadian drinker Rioja has three identifying features: Tempranillo, American oak, and Aging Requirements.

Tempranillo is the grape of Spain and is grown under 14 different names across the country, but is associated with no other region as strongly as La Rioja. “Tempranillo is important to us”, says Ana Fabiano, the Consejo Trade Director and author of the book The Wine Region of Rioja. She remarks that her favourite part of her own book is the section where different winemakers attempt to characterize Tempranillo’s importance. For herself, Ms. Fabiano finds the descriptor of ‘violets’ most evocative but also finds herself characterizing the grape by where it’s grown and believes that it finds its finest expression in Rioja. If Tinta de Toro can be described as higher in alcohol and Tinto Fino can be described as rustic, then it follows that where it’s grown in Rioja also matters.

There is a brief consideration over lunch of the habit of some writers to identify wines as masculine or feminine, and our hosts are quick to point out that while Tempranillo is often referred to with the female pronoun, the local Riojan nickname for Tempranillo is ‘signorito’ – which roughly indicates the man that every woman wants and the man that every man wants to be. Needless to say, it is central to Rioja’s identity.

Chef Jitin Gaba and Sommelier Lorrie O’Sullivan of TOCA

Yet, there are other grapes in Rioja, too. While red Rioja is strongly identified with Tempranillo, it is also traditionally known as a blend including Garnacha, Mazuelo (Carignane), Graciano, and Maturana Tinta (unique to Rioja). One of the distinctions that can be made between modernist and traditionalist Rioja is the increasing presence of 100% Tempranillo wine.

Garnacha has largely given way to more Tempranillo plantings and in Rioja Baja, Garnacha’s traditional stronghold, it has led to some of the youngest vineyards in the region. This is largely due to climate change; as Rioja Alta and Alavesa get riper fruit each year, they do not depend so much on the alcohol, ripe fruit, and lower acidity of Baja for their pan-regional blends, which in turn has pushed Baja to re-focus on their own quality. And quality in Rioja usually means planting Tempranillo.

Perhaps the most interesting minor player in the red Riojan blend, however, is Graciano. As Ms. Fabiano notes, it “seduces winemakers” with its fragrant and spicy notes, often in the white pepper range. At 1.76% of total plantings in Rioja, it is indeed a bit player. Graciano is a difficult grape to grow, which perhaps accounts for its low plantings, but with a naturally low pH it can offset the one principal weakness of fast-ripening Tempranillo, which is low acidity. Graciano is reportedly sensitive to American root-stock (which would explain its low yields) as well as being strongly terroir-specific. Graciano is also an indicator of longevity for Rioja reds for some, understandable given its contribution of acidity and tannin to the blend. There are a few mono-varietal examples made in Rioja and one in particular has made it Ontario (reviewed below). As Jancis Robinson’s book Wine Grapes notes, “[w]ord of the variety’s qualities is clearly spreading.”

While most Canadian drinkers hear the name Rioja and think Tempranillo and thus red wine, white Rioja does exist and it can offer various pleasures for those who know to seek it out. Indeed, the Chateau Ygay Gran Reserva Blanco 1986 was recently the top wine from Rioja for Parker critic Luis Gutiérrez, making waves with its 100-pt score. This very traditionally made white Rioja spent six years in cement and then a mind-boggling 21 years in barrel before being bottled in 2014. White Rioja generally relies principally upon Viura (Macabeo) and secondarily on Malvasia (as well as the recently discovered mutation Tempranillo Blanco), but really gains its remarkable character not varietally, but through extended oak aging. Viura is the Vidal of Spain; flat and unremarkable, producing some truly insipid wine, but under the right conditions it can attain greatness. White Rioja is now a growing category and not just among wine geeks.

The second principal feature of red Rioja is the use of American oak. For many, it is this traditional use of American oak which can either comfort the habitual drinker of Rioja or keep others away with its sweet coconut and dill notes. While there’s an increasing focus on French oak for top bottlings, it is this American oak profile which enabled the top Rioja of yesteryear to achieve the complexity and longevity it would become famous for. Combined with ripe fruit, this extended aging in used American oak produced many memorable wines as demonstrated by Chateau Ygay and many other centenary bodegas still to this day.

When the late Spanish expert John Radford’s book The New Spain came out at the end of the millennium, it described a Riojan wine industry on the cusp of change. Spain was split between modernists and traditionalists and like so many other regions throughout Europe one of those differences was the use of new French oak. For many of the old guard amongst Rioja observers, like Gerry Dawes, “too many of the modern wines seem to be imitating wines from such places as Napa Valley or even nearby Ribera del Duero, making a style of wines that they think the market is asking for.” Quoted on Tom Perry’s excellent InsideRioja blog, Dawes acknowledges that there are good modern wines but warns that fashion is the enemy of honest wine.

Wines with a true sense of place–it can be terroir or it can be a style of wine like Sherry or Champagne or like La Rioja wines used to be–are unique, not copies. And when unique wines find a successful place in markets outside their regions, their long-term success is dependent on that uniqueness that sets them apart, not a sameness which makes them as generic as Brand X and thus much more sensitive to price competition.

These modern Riojan wines are popular with North American palates for their ripe fruit, high alcohol, and intense oak regimes, often through the use of new French oak. To elaborate Dawes’ point, is Rioja’s identity fused with the aroma of American oak and hence a part of it’s sense of place as a style of wine? I do not think so. When we come to talk about oak and styles of wine, the truth of that lies with each bodega, not the region.

Which brings us to our third identifying feature of Rioja, the aging requirements. It is this system of quality which lies at the heart of the split between modernists and traditionalists. The younger generation wants to make wines which are terroir-specific and driven by quality viticulture and winemaking, like much of the rest of the quality wine world. Wines, which saliently, are ready to be sold within a year or two, not a decade or two.

Traditionally, one of the distinct features of Rioja is the fact that some of the wine is aged for longer periods before being released to the public, particularly in the case of Reserva and Gran Reserva wines. These minimum aging requirements in Rioja are nominally tied to quality, with the best wines in the best vintages being allocated to Gran Reserva, for instance. This, however, is not necessarily so. Quality-conscious producers who want to distinguish their wines from others who are not so quality-driven, find it difficult to do so when the level of quality relies simply upon length in barrel and bottle.

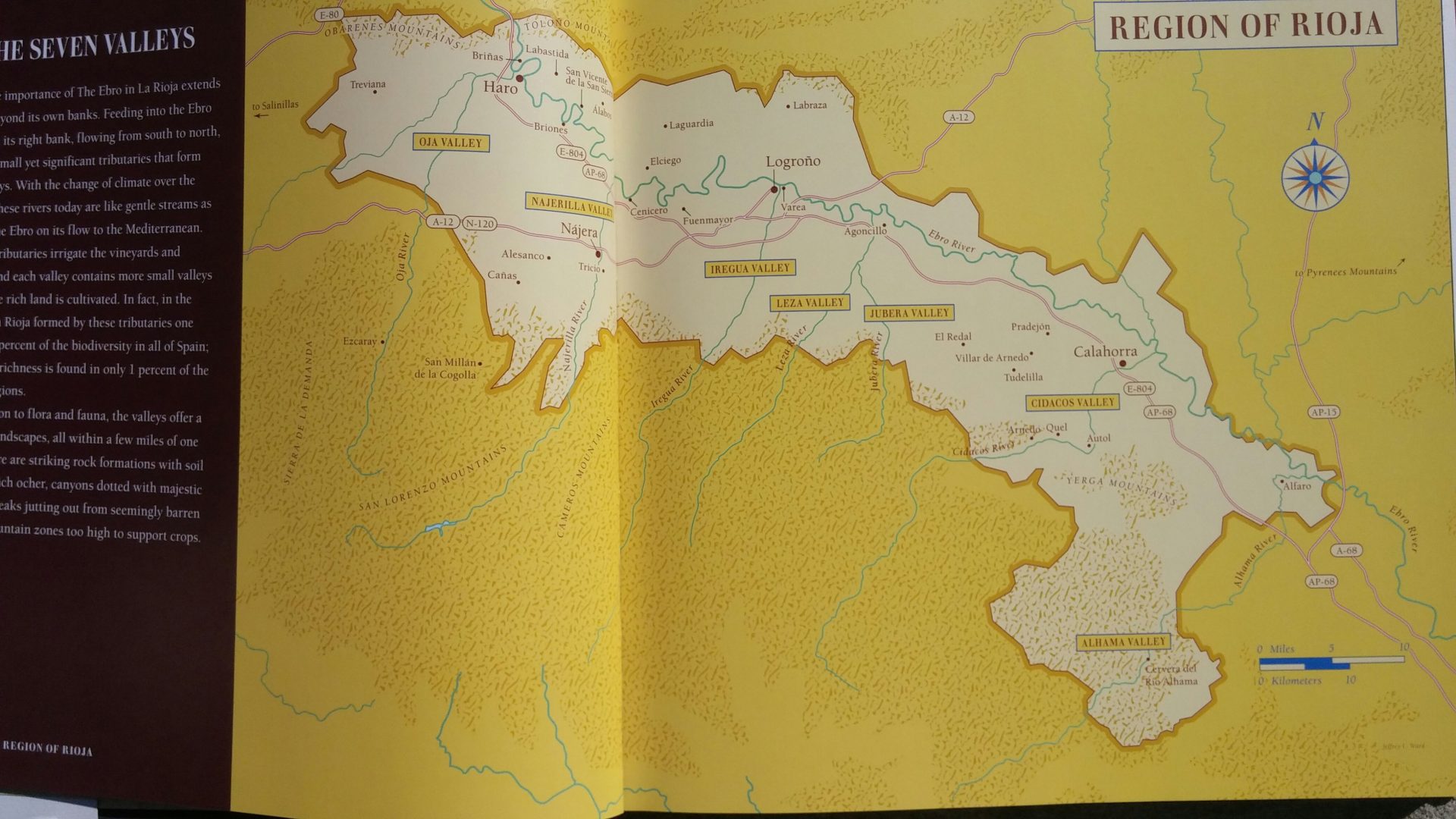

The Seven Valleys of Rioja from Ms. Fabiano’s book “The Wine Region of Rioja”

There is a new push within Rioja for terroir-specific wines, in line with most other wine regions, based broadly on the Burgundian village classification. Telmo Rodriguez, one of Spain’s leading winemakers, has long called for such a village classification. The fairly recent (1998) regional designation of the 3 sub-zones of Rioja – Alta, Alavesa, and Baja – is now giving way to a more detailed look at the terroir and specific geography of the region. Ms. Fabiano’s book, for instance, details the seven valleys which influence viticulture in Rioja and she adds that the mountains are the most important geographical feature in the area, something which is not spoken about enough in regards to Rioja.

Single-vineyard designations are now cropping up as “viñedos singulares” or ‘singular vineyards’, an epithet meant to indicate not merely single estate but also a cru, or vineyard of quality. Larger producers who rely upon pan-regional blends will predictably resist this change, but as Tim Atkin MW noted on Twitter on a recent trip to Rioja, “the horse has bolted”.

An intriguing alternative to the village-designation proposal comes from Pepe Hidalgo, former winemaker at Bodegas Bilbainas. He suggests dividing the region into 9 sub-zones, based on climate, elevation, and soil as an easier next step. Hidalgo believes that with 146 municipalities, a village-designation would be needlessly confusing for consumers, especially if you include the extra complication of vineyard designations.

Very broadly, for the typical Canadian drinker, Rioja is identified through the characteristics of grape, oak, and age. As we’ve seen, these defining markers are themselves being challenged. What then does the educator, writer, or sommelier tell the customer about Rioja? Arguably, we still have a lot to teach drinkers about these three things, though that hasn’t stopped anyone from drinking more. What is driving this surge?

I would argue that a lot of this growth has to do with the kind of Rioja available at the LCBO. Overwhelmingly, as far as most people know, wine from Rioja is red. There are 148 red Rioja wines available on the shelves, ranging from $11 to $265 compared with only 8 whites and 5 rosados. Many of these wines are big brands and are made to appeal to the North American palate, but you can still find more traditionally-made Rioja wines on the shelves. The rich, sweet, alcoholic, and new French oak 100% Tempranillos are themselves like a stepping stone to the more classically-styled and restrained bodegas. For every Bodegas LAN there is a López de Haro.

The LCBO also knows its customer base, and Spain is particularly well-positioned to reap the benefits of consumers who are continually buying up. The average retail price for a bottle of Spanish wine is $15.61, higher than most, exceeded only by California and New Zealand. The average price of a European bottle purchased at the Board is $14.76 ($27 in Vintages) and the biggest growth by price category is between $15 and $20. Spanish wine, and in particular, Rioja, is another ready-made stepping stone for drinkers who are beginning to explore quality wine. For many drinkers, age is a sign of quality, and where else can you get 6-year old wine for under $15? It would be foolish for the Consejo to dispense with the one characteristic which may be driving growth. However, sooner or later, people realize that age does not simply equate to quality. The Consejo needs to figure out their quality proposition sooner rather than later.

Politically and geographically, the Consejo has faced some challenges, particularly from the revolt of Alavesa producers who are politically Basque, but also from independently-minded producers like Artadi leaving the Consejo. These are growing pains and change will only happen incrementally. “Rioja is like an ocean liner. It needs time to change course,” notes Ángel de Jaime, past president of the Consejo (quoted on Tom Perry’s InsideRioja blog). With 16,000+ bylaws on the books of the Consejo and 600 plus wineries to administer, it is indeed a massive ship to turn.

With terroir-specific and single vineyard Riojas now a fait accompli, I believe there is still space for DOCa Rioja to be defined by its past. In truth, the way forward for Rioja lies in combining these two approaches: in retaining its unique selling point of aging requirements; and in not being satisfied with relying on being a “wine of style” like Champagne or Sherry for its sole sense of place, but embracing its own terroir and to focus on viticulture and not just vinification. After all, they’re even starting to do it in Champagne.

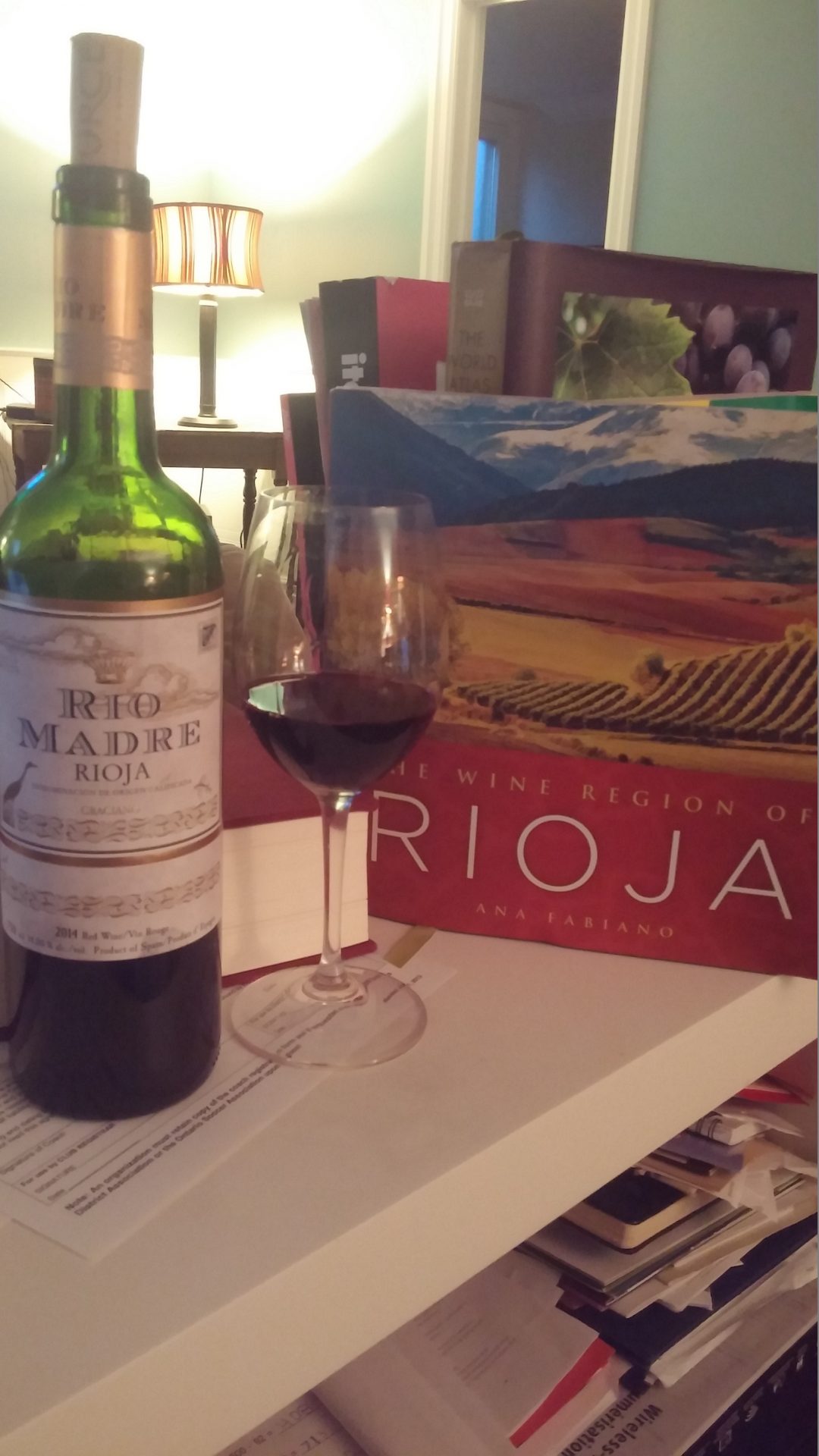

2014 Bodegas y Vinedos Ilurce Rio Madre Graciano – Widely available. Vintages #354753 $14.95

100% Graciano. From the slopes of Monte Yerga in the Rioja Baja, this wine is technically a Joven spending only a few months in used American and Romanian oak. Deeply coloured, with a distinct purplish hue, the wine is very charming on the nose, floral, dried violets, crushed black raspberry with a hint of rosemary. On the palate it shows dry, sapid, low tannin, showing its structure through taut acidity. The fruit is intense with fresh wild blueberries backed by a slight earthiness. It wears its 14% abv well, finishing spicy with medium length and remaining fresh and intriguing with each sip.

![]()

Rio Madre Graciano

Wines presented at lunch:

2014 Finca La Emperatriz Viura – Wine Wire $17.95 (2015)

Fresh, light Viura, saved by medium plus acidity and 2 months lees contact. This is the new face of Viura, floral and citric. It remains to be seen if it can distinguish itself from a thousand similar wines. Sommelier O’Sullivan found this complemented the octopus better than the rosado.

Poplo – grilled octopus, potato, green bean, basil pesto

2015 Ostatu Rosado – Vintages #451211 $13.95 but virtually gone.

Blend of Tempranillo and Garnacha with a bit of Viura. Pale salmon pink, floral and slightly herbal, this Rosado is bone dry with fresh strawberry and ruby red grapefruit. Quite pleasing with refreshing acidity and a backbone of salinity. Short finish but like a kiss keeps you coming back.

![]()

2010 Tobía Seleccíon Crianza – $21.95 a dozen bottles left on the shelves.

85% tempranillo, 10% graciano, 5% garnacha. Aged for 20 months in French & American oak barriques. The modern face of Rioja, full, concentrated, and ripe. Sweet vanilla from the wood pairs with medium tannin. Depth but a little four-square. Could be mistaken for Ribera del Duero. Vintages #364828

![]()

The Coto de Imaz and the CUNE were presented together and proved as intriguing a comparison of two different vintages as it was of two different producers and their style. 2010 was, in Mr. La Puente’s words, a “beautiful vintage, abundant in both quantity and quality” while the hot 2011 produced lower acid wines of good depth. El Coto is a modernist estate, at the forefront of Riojan innovation while Cune (COO-nay) or CVNE, the Compania Vinícola del Norte de España, is one of the leading traditional Rioja producers. When pressed, Mr. La Puente admitted that the difference between producers trumped the difference between vintages.

2010 Coto de Imaz ReservaVintages #23762 $22.95

100% Tempranillo from Cenicero in the Rioja Alta. 17 months in new and used American barrique. A surprisingly traditionally-made Rioja. It is pale ruby, bricking at the edges, with moderate alcohol and a strong oak presence. Coto de Imaz is famous for its use of American oak, extracting intense dill and coconut aromas and this is only a slight exception because the oak seems tamped down to show the pure fruit of the vintage at the core of the wine.

![]()

2011 Cune ReservaVintages #417659 $24.95

85% Tempranillo with the rest made up of Garnacha, Graciano and Mazuelo in the classic style. 18 months used French and American oak. Surprisingly deep in colour, a hallmark of the atypical vintage, the wine shows warm and deep with ripe fruit. An intense and penetrating note of crushed violets and spice, the finish is long and balanced.

![]()

2007 Conde de Valdemar Gran Reserva – $29.95 widely available.

85% Tempranillo, 10% Mazuelo and 5% Graciano. 30 months French oak. A wine which manages to present as both modern and traditional. Good introduction to aged Rioja. Lifted nose, leather, cherry, oak. Deep, complex, and excellently paired by Sommelier O’Sullivan with local wild flower honey and the Cape Vessey from Fifth Town. Vintages #114504

![]()

Cape Vessey cheese board

(All wines are scored out of a possible five apples)

Christopher Wilton lives in Peterborough and is a wine sales representative for the Small Winemakers Collection, a wine educator at Durham College, a server, and the regional liaison on the CAPS board of directors. He is certified with CMS, is almost finished his WSET Diploma, and has his CSW.

Christopher Wilton lives in Peterborough and is a wine sales representative for the Small Winemakers Collection, a wine educator at Durham College, a server, and the regional liaison on the CAPS board of directors. He is certified with CMS, is almost finished his WSET Diploma, and has his CSW.