Wine and Art is an ongoing GFR series on the relationship between the two creative endeavours by working artist and author Lorette C. Luzajic.

Apparently, the wines I love most must all be paired with giant slabs of fiery red meat. Forget light broth or airy greens. The little blurbs all concur that the kind of complicated, sense-assaulting, spicy, chalk dry wines I like best need a spit and a hog and a keg full of chilli peppers to go with them.

I love meat- red, raw, yes. But one can only eat so much at a time, a constraint not paralleled by the joys that are in the bottle.

I love meat- red, raw, yes. But one can only eat so much at a time, a constraint not paralleled by the joys that are in the bottle.

Since I still have most of a bottle of Beronia’s Tempranillo Elaboracion Especial, my mind turns from food to where it always finds itself. Art. It dawns on me that meat is a staple subject in the history of painting. And since this stunning, waxy –in-a-good-way Rioja goes so well with the subject, it’s fitting that I haul out a few art books to pore over. Another favourite holds up just as well with mountains of meat- Australia’s Jacob’s Creek Reserve Barossa Shiraz is a fierce wallop of a wine that can hold its own beside the saltiest charcuterie.

Right now there is a very interesting option from Jacob’s Creek: the Double Barrel Shiraz. It’s an experiment: it was aged in barrels used to age whisky. This imparted a delicious and unexpected flavour to a staple. The only flaw is the 15% alcohol content, which you can taste over all those toasty blackberries.

Back to the table…

Compared to the portrait, the landscape, the Biblical, the nude, and the abstract, meat is a minor actor in art history. But it is a recurring theme nonetheless, and an ancient one.

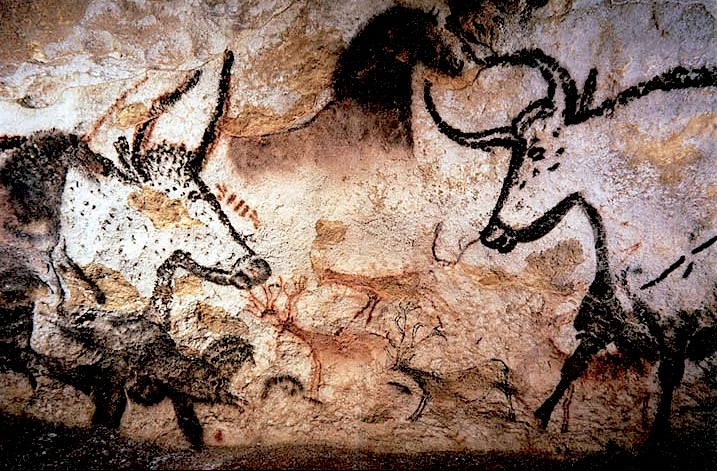

It was, actually, possibly the first subject in painting. Hundreds of caves in Lascaux, France, as well as Spain, Namibia, and Indonesia have yielded contact with forebears distant by 15 to 40,000 years, varying in age from region to region of the finds. And more recently, even older ones have been discovered. Most of them show bison, horses, aurochs, deer, boar, and fowl. They are, of course, practical or ritual invocations of the hunt.

Meat.

When one considers the power of art to convey the human story, the cave paintings become crucial rather than quaint. We came to understand ingenuity, how our early selves resolved to create pigment by mixing earth and stones and plants with animal fat to make crude colours. More, Humans were telling us about the most vital necessity in their lives. The new-old Paleo movement wrestles with the vegetarian one over what humans ate first or should eat, and I’ve been on both of those teams. Through cave art, the ancients are able to tell us themselves.

Now catapult forward 20 thousand years or more, and land in a peculiar world where the magnificent recent achievements of painting, cataclysmic allegories of faith and mythology, give way to a lot of dim and dusty fruit bowls with clocks and bones and lemons.

There were many reasons for the sudden appearance of so much meat in the paintings of post-reformation Europe. For all its dreary and dull reputation, and centuries since of critical condescension, still life painting is an intriguing tangle of lore. You could even say it is a kind of visual code or language to decipher.

On one level, the dead pheasant or skinned rabbit heaped on a table is there for the same reason as the lemon- status and rarity. We can’t imagine it now, but in those days, a pinch of spice and a few lemons came only by ship and cost dearly in human lives during trade. Most people didn’t own a timepiece, either. So these objects were interesting subjects in their own right.

It was also new that ordinary, albeit rich, people began to own art. This had been solely the realm of churches and kings. People wanted art depicting subjects relevant to their own lives, not just grand stories. This included food, objects, and landscapes, which also began to blossom as a subject around this time.

Peasants were usually more deprived of fresh vegetables than of meat, because they could keep chickens or a pig over the winter. But still lifes show a variety of dead animals, which reflected the leisure of hunting as a hobby. The variety of animals that turn up in still lifes is another clue: access to so many sorts of meat displayed hunting- leisure- and also wealth, since the poor couldn’t keep a zoo. Game pie was a popular food, and the more kinds of prey that went in it, the better. Note how many types of birds show up in this Adriaen van Utrecht.

That said, it wasn’t just about flaunting one’s excess. Still life paintings were stories of morals, reminding the good Calvinists to be thankful for what they had, and to remember to avoid gluttony and excess and to be charitable. That is why so many show a clock or candle or a skull as well- these, and the lifeless bodies of animals were all symbols that existence was temporary. There is a whole genre of still life devoted to this specific message, the Vanitas paintings.

Take a look at some work by artists Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, Giuseppe Recco, Elias Vonck, Alexandre-Francois Desportes. You’ll be able to stomach them better with a side of Ramirez del la Piscina. This 2011 Crianza has a real kick. On one level it is silky and elegant and tidy. On another, it is tricky, full of wood and granite. It’s almost perfect.

I consider for a moment dipping the dripping gob of beef speared in my right hand into the elixir in my left.

Such an urge is rooted in gourmet good taste as much as in primitive barbarism. Red wine is a formidable ingredient in a good many beef recipes. But in this case the impulse was triggered by Goya. Goya is famous for his gruesome paintings of mythological monsters gruesomely tearing into innocent flesh. But I’m looking at an exquisite and disturbing work that depicts a bloody heap of salmon.

When not painting assassinations or political corruption or asylums or the plague, Goya created quite a number of meat and fish paintings. He was fascinated with the darker side of things, and explored with blunt ferocity images that disturbed rather than evoking beauty.

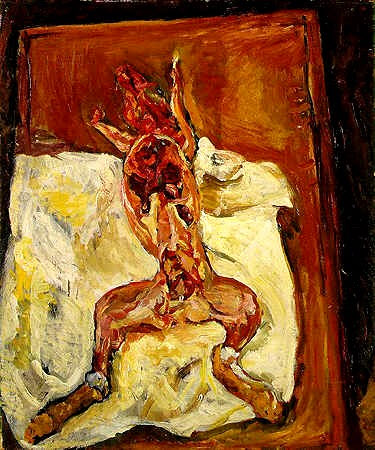

Another artist who routinely depicted meat was Chaim Soutine. His “carcass paintings” are raw, bloody, and splayed in such a way as to appear grossly pornographic. They should come with trigger warnings.

Soutine’s relationship with his subject matter was complex. The revulsion response is not a mistake. Soutine said himself that his infamous beef carcass was a kind of exorcism. In his words, he wanted to liberate a cry inside himself after witnessing a butcher kill a bird.

Because of the visceral emotion of the piece, it is often used by evangelical vegetarians, but Soutine wasn’t saying it is immoral to eat meat. He was, rather, confronting the theme of life and death. He was working out issues of personal religious symbolism and exposing the vulnerability we all share in the face of the inevitable. He was exposing our naked selves, our insides, our essential reality.

Soutine painted from actual props. He hung this cow in his studio and dowsed it in fresh blood to renew its colour. The putrefaction and stench of rot was part of the ritual he was enacting in his work- a real confrontation with the temporariness of flesh.

As we take our final steps across the killing floor to the present, I recommend a robust and sweet Gewurztraminer. Forget that matchy matchy white for light and red for dead adage. A bracing, syrupy jolt of ice cold white goes perfectly with the conclusion. Many Gewurztraminers are as strong as perfume, and can take on the cheeses of the foot variety as well as the gamiest of meats.

In contemporary times, the theme of meat often surfaces in art or pop culture. The subject is renewably edgy and transgressive – we have not and will not completely make our peace with consuming death. It is not something other animals think about. We are analytical and spiritual, and this conundrum of need and greed and evolution and nature churns in our minds. The symbolic parallels of meat are many: suffering, satisfaction, unity with nature, sexuality, nourishment, and identifying as both predator and prey.

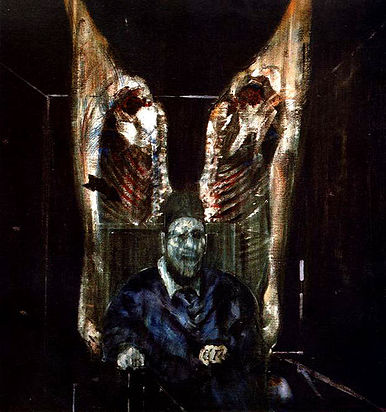

The suitably named Francis Bacon added meat to some of his ugly, topical portraits. And Lady Gaga’s meat dress was a triumph of a statement in an age where there’s nothing left to shock with. The sliced up horses and sharks that made the Damien Hirst famous will also make art history books. Alongside, and perhaps, trumping, the Duchamp urinal. And pictures of women’s body parts hanging from meat hooks appear throughout feminist art.

I confess I don’t really care for these more modern statements. There is a pervasive nihilism and if solutions to the dichotomy are presented, they are simplistic. It’s not as easy as the “meat is murder” faction of protest art believes. Our heritage diet is sacred and nourishing, and we are no more guilty for it than all the other animals who need meat. On the other hand, wantonly killing animals for the purpose of shocking art is depraved.

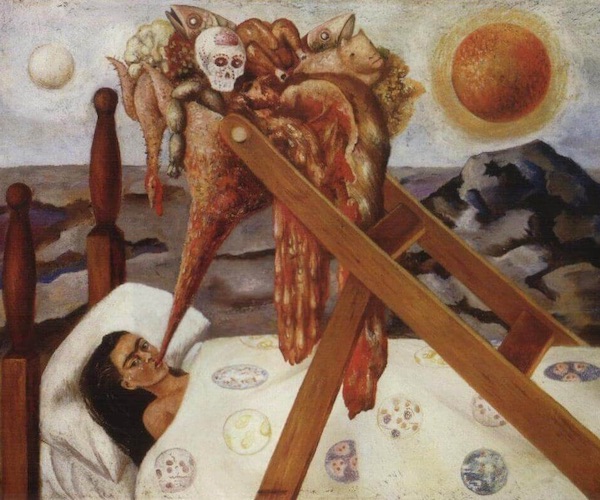

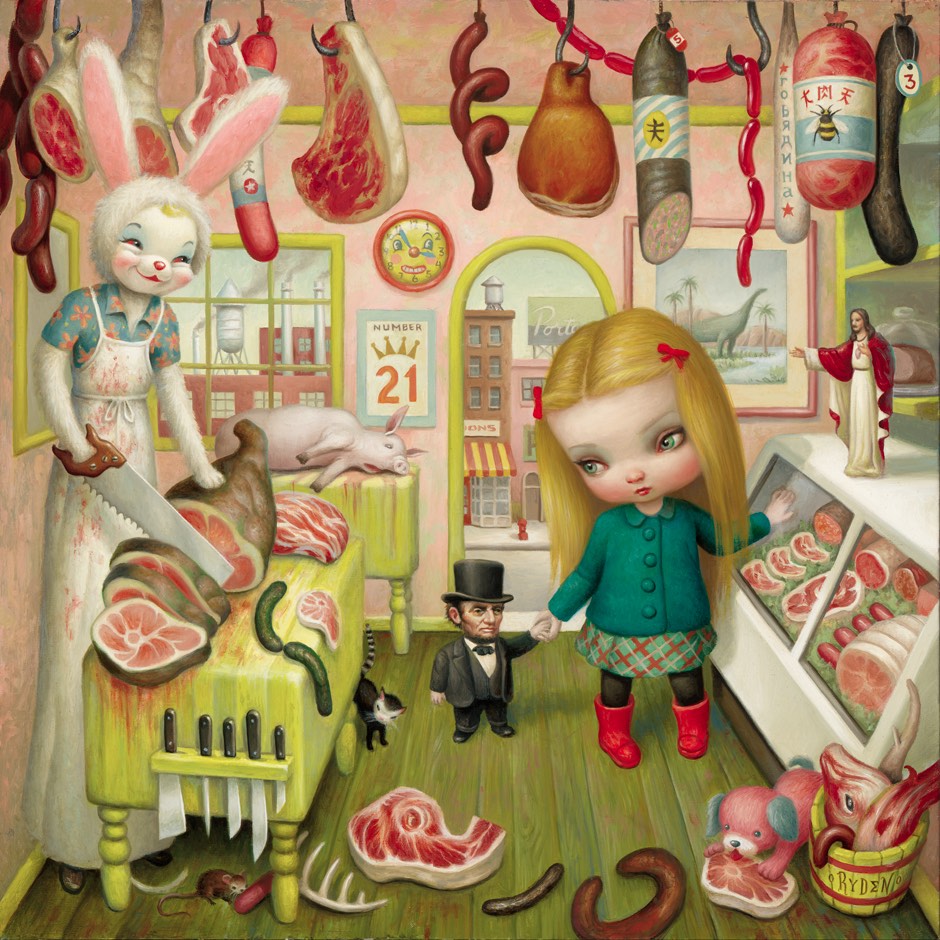

Perhaps my favourite depiction of meat in contemporary times is Mark Ryden. Ryden’s spectacular debut series, The Meat Show. The surreal paintings are from their own imagined Wonderland, with peculiar details and strange critters buoyantly flitting through a meat-stuffed curiousity cabinet of wonders.

Ryden says he is an avid meat eater but doesn’t want us to lose sight of the origins of what we put on our table. He is also toying with the religious ideas inherent in sacrifice. Indeed, a bit of etymology connects a few dots when he titles a character wearing a meat dress- months prior to Lady Gaga’s- “Incarnation.” The word contains the same root as “carnivore.” It’s meaning is “in the meat” or “in the flesh.”

Ryden’s paintings gorgeous, with as much jarring charm as the last of this perfume in my glass. He is brilliant for coming at the issue from a different angle. It’s not so much coming to terms with being made of flesh and facing death. Rather, he’s reminding us, in his own words, that “meat is about life.”

Lorette C. Luzajic is a Toronto writer and artist. Her collage-centred paintings use mixed media to explore ideas from art, literature, history and culture, always fascinated by the intersection of human creativities. Exhibition of her work is ongoing throughout Toronto, including such venues as the Spoke Club, the Royal Ontario Museum, the Flying Pony Gallery, Toronto Outdoor Art Exhibition, and the Artist Project, and it has been shown in Belfast, Brisbane, Los Angeles, Edinburgh, and beyond. In addition to occasionally writing about her other passions, food and wine, she is the author of more than ten books of poetry, short fiction, and essays, including Funny Stories About Depression, Fascinating Artists, and Kilodney Does Shakespeare. She is the editor of the new online journal, Ekphrastic. Visit her at mixedupmedia.ca. Photo by Ralph Martin.

Lorette C. Luzajic is a Toronto writer and artist. Her collage-centred paintings use mixed media to explore ideas from art, literature, history and culture, always fascinated by the intersection of human creativities. Exhibition of her work is ongoing throughout Toronto, including such venues as the Spoke Club, the Royal Ontario Museum, the Flying Pony Gallery, Toronto Outdoor Art Exhibition, and the Artist Project, and it has been shown in Belfast, Brisbane, Los Angeles, Edinburgh, and beyond. In addition to occasionally writing about her other passions, food and wine, she is the author of more than ten books of poetry, short fiction, and essays, including Funny Stories About Depression, Fascinating Artists, and Kilodney Does Shakespeare. She is the editor of the new online journal, Ekphrastic. Visit her at mixedupmedia.ca. Photo by Ralph Martin.