“But we don’t always have fresh meat in the country,” Bevvy says. “Only right after we butcher. We have to cure it to keep it. Some we make into sausage, some we pack into solid jars and steam it; we smoke beef and ham. What we like best is the summer sausage: it is beef and pork ground real fine with seasoning and saltpeter, then stuffed tight into cotton bags the size of a lady’s stocking and smoked for a week in maple smoke.”

“We eat that every day; we never get sick of it, ” David says.

“We couldn’t live without summer sausage,” little Amsey says as he slaps a slice on a piece of bread and butter.

“Ach, we could live without only we would rather wouldn’t,” Bevvy says.

Edna Staebler, Food That Really Schmecks (1968)

Canada’s late great culinary author and participatory journalist Edna Staebler is always on trend, or maybe beyond it. To write her masterpiece, Food That Really Schmecks, Staebler embedded herself into the Martin family, quoted above. As Old Order Mennonites, they taught Staebler much, including a love and respect for nose-to-tail eating and charcuterie that sounds very contemporary indeed.

Summer Sausage, the great dry-cured meat of Southwestern Ontario, is a fermented food. That’s what gives it its trademark twang. In a dry cure, room temperature meat is mixed with salt and sodium nitrate (instead of the more volatile potasium nitrate, ‘saltpeter’), which guard against harmful bacteria and encourage good microflora to transform raw flesh into a dense, chewy treat. For this to happen it has to be humid, which seems counter-intuitive when the process is described as “dry”. Michael Ruhlman and Brian Polcyn in their definitive modern manual, Charcuterie* (2005), explain:

Humidity is necessary for proper drying. If the air is too dry, the surface of the meat can dry out, harden, and then prevent the interior moisture from escaping, resulting in a rotten sausage.

So, for pioneering Mennonites, and old order ones who keep to old fashioned ways, Summer Sausage was made in the humid seasons, hence the name. That it will keep without refrigeration, cemented the moniker, and makes properly made Summer Sausage very seasonally appropriate.

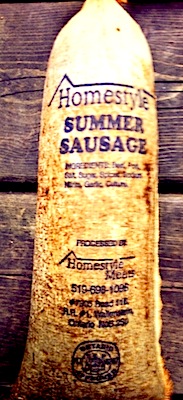

Bought at a roadside shop near Kitchener-Waterloo, and transported to my home by a kind relative recently, a Homestyle Meats summer sausage is emanating a smoky umami aroma throughout my kitchen. Made in Wallenstein, its ingredients list is perfectly simple: ‘Beef, Pork, Sugar, Sodium Nitrate, Garlic, Culture’. I spy what looks like chilli flakes, a few pepper corns and maybe a coriander seed or two embedded in the meat, too. It’s wonderfully tangy, with just a hint of spice burn – but not enough to dissuade my kids to gobble it up as quickly as me. Like Amsey Martin, we like it plainly served, right off the knife.

*If you’ve had a plate of house-made charcuterie at a restaurant anywhere in the English speaking world in the last eight years, there is an extremely high possibility that a copy of Charcuterie: The Craft of Salting, Smoking and Curing is sitting on a shelf in the kitchen or the chef’s office.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him at twitter.com/malcolmjolley

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him at twitter.com/malcolmjolley

I sure would like a recipe on this great summer sausage. Zurich, ON

I am from Kitchener, and now live in Coastal Maine. I miss the meats and sausages from the Farmers Market (the Old Market) in particular. I grew up on summer sausage, and my first full time job was at JM Schneiders, back in 1961. Ahh I miss my summer sausage. A small group of Mennonites from the Elmira area have been moving onto farms not that far from here. I will have to see if they are making summer sausage and old style pork sausage.

Is there any way to by Waterloo county style summer sausage in the States. Anyone importing it?