Finally, and perhaps with a tinge of sadness, we reach the end of my intensive 10 part series of pieces on my beloved region of Beaujolais. I guess that with the third Thursday in November’s Beaujolais Nouveau release sneaking up upon us, the timing could not be more apropos. So after completing such an in depth study of these vineyards situated in the very south of Burgundy, what did I actually learn?

- White Beaujolais?

- Carbonic Maceration

- Assigning Genders to the Beaujolais Crus

- The New School of Beaujolais Part One

- Can Beaujolais Age?

- The Role Of The Negociant

- Making “Natural” Beaujolais

- The New School of Beaujolais Part Two

- Does Vintage Matter in Beaujolais?

- What Makes Gamay Great?

Beaujolais is Gamay, of this there is no doubt (well, apart from some of that delicious Chardonnay in Beaujolais Blanc), and in speaking with innumerable Beaujolais Winemakers there are all extremely proud to be working with the region’s signature varietal. Saying that, I do feel that there is a considerable amount of Pinot Envy going on in many of the wineries between Macon and L’Arbresle. There is a large contingent of producers who choose to adhere to the “Burgundian method” of vinification, and by that they really mean treating the Gamay grape as if it were Pinot Noir, so basically a combination of destemming, délestage (rack and return), pigeage (open top punchdowns), and ageing in barrels. Sometimes I wonder if they do this as they would like their Beaujolais to taste more like Burgundy? Yes, technically Beaujolais is in Burgundy, but you know what I am getting at here. Granted, the bottlings of producers such as Jean-Paul Brun are undoubtedly fine wines, but does this particular treatment of the fruit and then the wine make for a truly authentique Beaujolais?

Well, yes… and no.

In my mind, controversially, the complicated mosaic of terroirs and climats throughout the 10 Beaujolais Cru, through Beaujolais Villages, to the vast garden that is Beaujolais, are perhaps capable of producing wines with the myriad complexities and nuances that one can sometimes find in the Côte-d’Or to the north. Perhaps the “Burgundian method” is the best way of transferring the character of the vineyard into the glass, as it has arguably worked well for centuries for the Burgundians.

And then there is the rather convincing argument that this “Burgundian method” was actually the the traditional method of vinification in Beaujolais 100 – 150 years ago. I mean, the chances of Winemakers back then having anything close to the means that would allow them to ferment in completely closed wooden vessels is a bit of a stretch of the imagination is it not? Think about it…

Which brings us rather neatly to the subject of Carbonic Maceration…

When I was studying wine some 20 years or so ago the term was always bandied about accompanied by a grimace, and so we were taught that the act of Carbonic Maceration was a nasty thing… a terribly bad thing that made a wine smell like pear drops or bananas (Isaoamyl Acetate and/or Amyl Acetate).

I have since come to believe that these disgusting olfactory misgivings come through the use of the notorious 71B yeast in the absence of oxygen, something that, at the height of the Beaujolais Nouveau boom, most of Beaujolais was guilty of inducing.

Although a tiny bit of intracellullar fermentation would have happened naturally, true partial or full carbonic maceration was not introduced until the late 1950’s when French Scientist and Negociant Jules Chavet declared it as the future of the Beaujolais region as a whole. Interestingly enough Chavet is also seen as the Father of the French Natural Wine movement…

Throughout my voyage of discovery in Beaujolais I came across a sizeable number of Winemakers who choose utilise this much maligned process, whether that be in its partial or full incarnation. The amazing thing was, so few of the wines exhibited the aromatics that I had come to believe carbonic maceration brought to a wine. I was truly astonished.

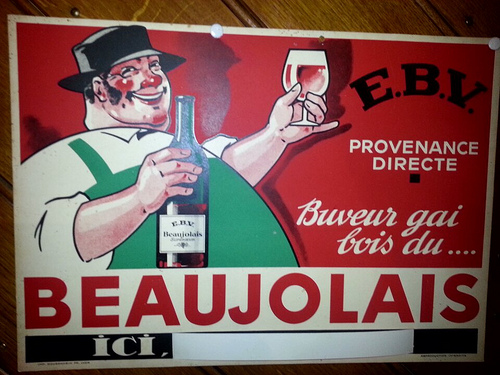

Finally, let’s touch upon the tricky subject of Beaujolais Nouveau…

Referred to by esteemed French wine critic François Mauss’ as “vin de merde” (shite wine), there was a day when Beaujolais Nouveau was sought after by much of Europe and North America. Back at Wine School in Scotland we were informed that Beaujolais Nouveau was the French Winemakers’ way of getting rid of all the wine the French themselves wouldn’t drink, i.e. “Let’s fob it off on all those clueless Anglophones”

Now there may have been a grain of truth in this, but although export sales of Nouveau have dropped dramatically over the past decade, there is a still a thirsty audience for the stuff back home in France, where it is consumed with gusto and by the gallon in the gastronomic centres of Lyon and Paris. There it is seen as a celebration of the vintage, to be slugged back with friends without too much thought, without too much dissection. I can actually see myself getting quite into it if I were there. It’s seen as being fun, and nothing more, with seasoned wine drinkers understanding that they have to wait until the March releases of the Beaujolais and Beaujolais Villages before they begin to find anything more than simple fruity aromatics in the glass. I fear that perhaps many of us have become much to snobby/snotty to truly appreciate the fête of Beaujolais Nouveau, and that is probably a sad thing.

In speaking with my peers I am aware that Gamay is the word on everyone’s lips these days… Sommeliers in Canada find it increasingly hard to keep Beaujolais on their lists as it sells out so quickly, what with it being so damn food-friendly. I believe that there are very few varietals that are capable of as many facets as the Gamay. In speaking with so many passionate and committed Winegrowers throughout Beaujolais I believe that we are looking at a full-on renaissance in this region. There is a very, very bright future ahead for Beaujolais.

My thanks go to SOPEXA and InterBeaujolais for making my trip to Beaujolais possible.

…

Edinburgh-born/Toronto-based Sommelier, consultant, writer, judge, and educator Jamie Drummond is the Director of Programs/Editor of Good Food Revolution… And hopefully this series will have convinced a few of you to return to Beaujolais.

Edinburgh-born/Toronto-based Sommelier, consultant, writer, judge, and educator Jamie Drummond is the Director of Programs/Editor of Good Food Revolution… And hopefully this series will have convinced a few of you to return to Beaujolais.