Why is Atlantic Cod from Newfoundland being sold as “MSC certified sustainable” while under consideration for endangered species protection?

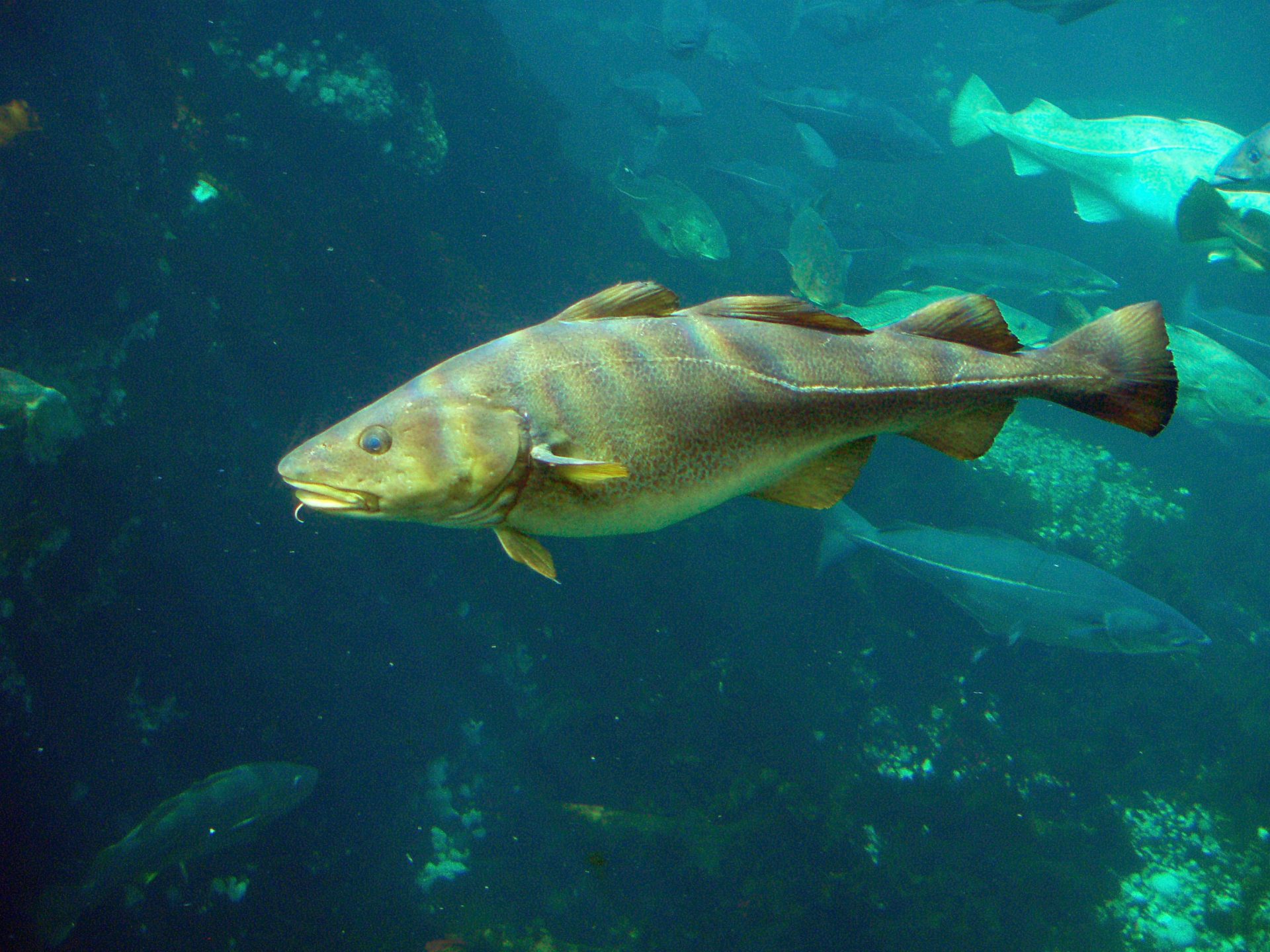

In 1992, Atlantic Canada’s lifeline collapsed. The waters surrounding Newfoundland, once teeming with millions of tonnes of Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua), saw their numbers tumble to nothing. It was commercial fisheries that had depleted cod populations after decades of overfishing. Seemingly overnight, Newfoundland’s myriad coastal communities watched their economic, cultural, and culinary mainstay disappear. Fearing the outright extinction of Atlantic Cod, a fishing moratorium was imposed on the enormous Northern Cod fishery in July of 1992 – a protection that has remained in place ever since. While crucial for the recovery of the species, the moratorium put nearly 30,000 Newfoundlanders – almost 12% of the province’s population – out of work. Most of the unemployed fishery harvesters and workers were forced to access government aid, and in the decades following the moratorium, tens of thousands abandoned the province. The collapse of the Canadian cod fisheries is still regarded as one of the most egregious examples of natural resource exploitation and mismanagement in history, and its devastating environmental and economic impacts remain today.

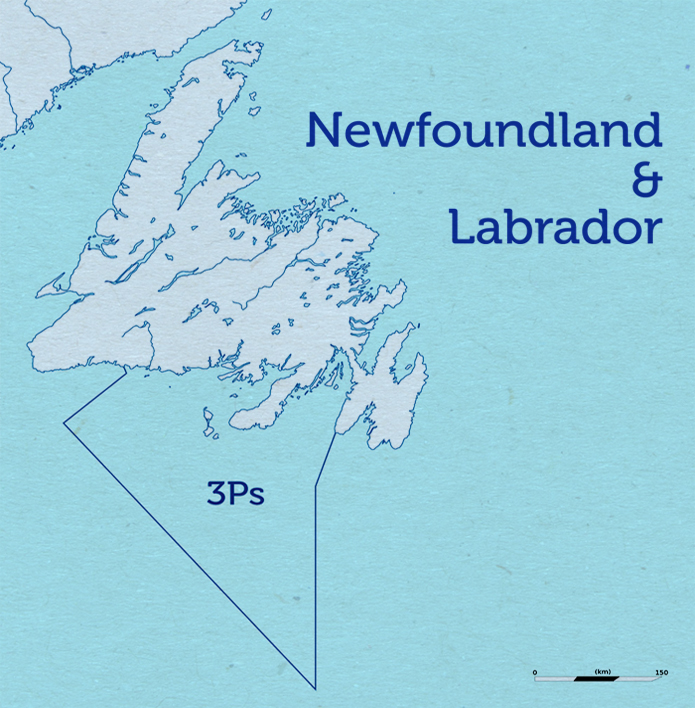

Given this tumultuous history, it may seem surprising that one of the associated fishing zones, 3Ps, was recently able to earn certification as a sustainably-managed fishery and seafood source. The 3Ps zone, located along the Saint Pierre Bank south of Newfoundland, was severely impacted by the sharp decline in Laurentian cod in the 1990s. However, recent years have seen a tentative rebound in the fish populations, and some, including the Marine Stewardship Council, or MSC, have pointed to this as an indication of reprieve for Newfoundland’s beleaguered cod industry.

3Ps is a fishery designated by the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO). NAFO is an intergovernmental fisheries science and management organization whose mandate is to ensure the long-term conservation and sustainable use of the fishery resources in the Northwest Atlantic.

On March 22, 2016, the MSC affirmed the health, vitality, and commercial viability of 3Ps by granting it a seal of approval as a “certified sustainable” cod fishery. This means that Newfoundland’s Icewater Seafoods, the initiator and chief beneficiary of the certification, will now be able to supply the once-failing cod as a certified sustainable product to its customers, including UK giant Marks & Spencer. Ocean Choice International, the other fish harvester, will likewise benefit from the certification process. The heroic narrative seems clear: an overfished species on the brink of extinction makes a comeback, becomes an environmentally sustainable product through good management and with the MSC’s blessings. It’s an ecological and economic win-win, particularly for Newfoundland’s long-suffering fisheries. Yet, the certification is not without controversy. Although the story seems to signal their recovery, the 3Ps cod are not out of danger yet – not by a long shot, according to Susanna Fuller, the Marine Conservation Coordinator at Nova Scotia’s Ecology Action Centre (EAC).

Fuller and the EAC, with support from the David Suzuki Foundation, have taken the lead on questioning the validity of the MSC’s approval of the 3Ps cod fishery. Last February, Fuller travelled to London, UK to formally object to the certification process. Pointing out that the MSC’s standards for determining sustainability ignore Canadian law and conservation expertise, she stated, “they undermine government policy and scientists.” Fuller cites a 2015 assessment report by marine researchers associated with the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans, or DFO. The report judged the 3Ps cod stock to be in a ‘Cautious Zone’ – not in urgent danger of extinction, but nowhere near the health that might be associated with a sustainable population. Supporting statistics show a two-year decline in the 3Ps stocks, as well as an unusually high-mortality rate for the fish, with close to half of the mature population dying between 2012 and 2014. “Basically, the fish aren’t living to be old enough to spawn,” notes Fuller. The combined factors of declining stock, high mortality rates, and lower spawning potential could have severe impacts on future generations of 3Ps cod.

Even more alarming, the Laurentian North Atlantic Cod, of which 3Ps is a subset, was assessed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Species in Canada (COSEWIC) as endangered in 2010, and have remained under consideration for endangered species protection through Canada’s Species At Risk Act (SARA) since 2013. The MSC has ignored this important scientific designation. Given the near endangered status of northern Atlantic Cod, the EAC has raised serious questions as to why the assessment process was permitted to go ahead in the first place, beginning in 2014. The David Suzuki Foundation has argued that 3Ps should have never even been entered into pre-assessment through a 2011 Fishery Improvement Project, which was monitored by the World Wildlife Fund. Alan Sinclair, the co-chair of COSEWIC’s Marine Fish Committee and a retired DFO scientist, stated, “the 3Ps certification never should have happened.” Beyond the pre-assessment and assessment phases, how is 3Ps – a fishery associated with a species at moderate to explicit risk of endangerment – allowed to achieve “certified sustainable” status as a commercial seafood source? Moreover, how can a certifying body like the MSC effectively ignore government and scientific expertise?

To begin to answer these questions, one needs to examine what the Marine Stewardship Council is, and how it operates. The MSC is a private, international organization dedicated to the certification and eco-labeling of wild-caught, sustainable seafood products. Established in 1997 through an agreement between the World Wildlife Fund and multinational Unilever, the MSC was launched as a response to the collapse of the Canadian cod fisheries and feared impacts on both the environment and global economy. While its mission is rooted in the former, its methodology privileges the latter; that is, the MSC works through the seafood industry to incite ecological change.

By being applicable to each facet of the seafood supply chain, the MSC’s certification program ensure that their standards of sustainability and traceability are applicable to all of the products that feature their blue consumer eco-label. MSC partners with a third-party evaluator to examine the practices of commercial fisheries, brands, retailers, and restaurants to match its independent MSC Fishery Standard. The MSC prides itself on the scientific rigour of its assessment standard, through which the 3Ps fishery has been certified, along with McDonald’s Filet-o-Fish, created from MSC-certified sustainable wild Alaskan Pollock, and seafood products available through global retailers like Wal-Mart.

What is important to note is that the MSC works through the industrial food system, and specifically with large fisheries and multinational corporations. Ostensibly, this targeting of major global buyers to provide a model for sustainable seafood consumption will create market incentives for independent and smaller-scale seafood businesses to change their practices. Furthermore, by initiating this trickle-down influence from large business to smaller business, the MSC’s theory of change is that greater stewardship and conservation of seafood resources will result. Yet, this logic is based on the same types of commercial enterprise largely responsible for the dangers facing marine-based wildlife. While it could make sense to target the most prominent entities in the seafood supply chain, it seems paradoxical to present McDonald’s and Wal-Mart – usually the icons of unsustainable and exploitative practices – as the faces of marine stewardship.

By extension of their partnerships with large multinationals, the MSC’s ethos also upholds high levels of consumption. According to Jay Lugar, the Program Director for the MSC’s Canadian office, “[the MSC] believes offsetting or curbing demand for certified sustainable seafood would do more harm than good until at least we get to the point where mankind is fully managing our ocean resources.” For the MSC, the very mechanism that ensures the sustained livelihood of marine wildlife is the public’s demand to consume it – a position that could easily be construed as contradictory.

The seeming inconsistencies of MSC’s approach become less puzzling in light of the Council’s primary income sources. This includes charitable grants from funders such as the Walton Family Foundation (of Wal-Mart fame), which contributed $2.5 million USD to the MSC in 2014 – more than half of the $4.6 million USD that the MSC earned in charitable grant income that year. The MSC also generated 75% of its annual income from licensing its consumer eco-label in 2014 – a practice buoyed by the organization’s corporate partnerships with powerhouses like Wal-Mart, Ikea, and Canada’s Loblaws. While the MSC is a non-profit environmental organization, its mission is severely compromised by its mutual support of the global seafood industry and its reliance on the royalties generated by its eco-label.

MSC “certified sustainable” offerings created by and available at Canadian retailer Loblaw’s. According to their 2014-2015 Annual Report, MSC has certified 10% of the world’s wild caught seafood. Image source: Intrafish.org

As Fuller has pointed out, the MSC is independent of government authority and uses its own evaluative criteria by which the health of marine species is assessed. However, there is one with one key exception: MSC policy states that it will not allow any species to enter into assessment that is actively protected under binding national or international conservation law. The problem remains, however, that any species assessed as endangered but lacking in explicit legal protections can still be entered into the certification process. In the case of Atlantic Cod, since the species has not been listed under SARA, it is fair game for certification under MSC rules. Sinclair points out that Canada has a poor track record of listing marine species under SARA, an issue he attributes to the DFO. “There are not enough people calling the DFO to task on how it protects endangered species. Marine fish species are consistently not listed under SARA. There are Atlantic Cod species that are not even sustaining themselves independent of fishing, yet these species are not given protection,” said Sinclair.

So what does this mean in the context of Newfoundland’s 3Ps cod fishery?

MSC’s privileging of large multinational entities, such as Icewater Seafoods and Ocean Choice International, leaves smaller, integral stakeholders out. Icewater and Ocean Choice were the only two fish harvesters monitored in the 3Ps certification process. This included a three-year Fishery Improvement Project as a precursor for certification, as well as the development of a conservation strategy for the fishing zone. No other fish harvesters were actively involved.

According to Fuller, “this is a huge problem – what we [the EAC] pointed out is that the client group [Icewater and Ocean Choice] only fish offshore, and this accounts for just 15% of the Total Annual Catch.” In other words, 85% of the cod actually caught in the 3Ps fishery zone was not a part of the MSC’s certification process. This directly impacts 3Ps’ small-scale, inshore fish harvesters, represented by the Fish, Food, and Allied Workers Union (FFAW). Keith Sullivan, President of FFAW-Unifor, indicated FFAW’s desire to be full partners in the 3Ps certification. According to Sullivan, “harvesters are most affected by conditions related to sustainability labels such as the MSC and should be part of the process. It is logical that harvesters be members of client groups in such a process where they have an ability to proactively work to improve sustainability.” It remains that this was not the case, which is especially concerning given that FFAW harvesters constitute a major component of Icewater and Ocean Choice’s business. Just three years ago, 420 of the area’s inshore harvesters sold their inshore catch directly to Icewater and Ocean Choice for processing. As a key stakeholder in the 3Ps fishery, FFAW members’ omission from the certification process represents an alarming gap in the data.

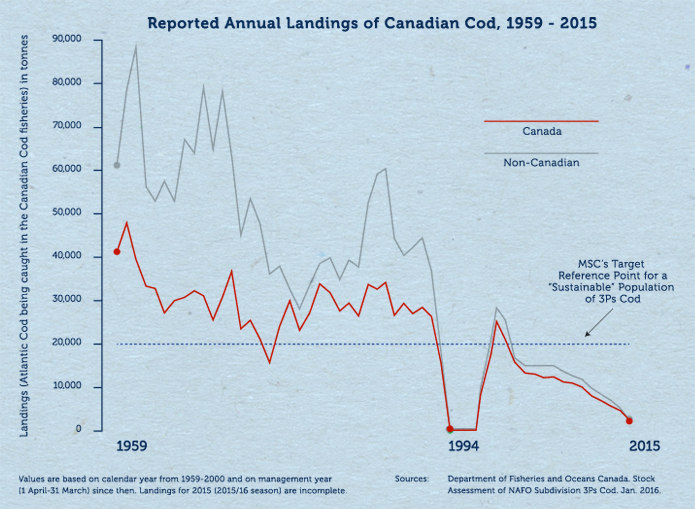

If the MSC’s oversight isn’t problematic enough, Sinclair, the EAC, and FFAW have also questioned the three-year target for the 3Ps cod’s spawning stock biomass (SSB), or fish mature enough to spawn. The certification’s third-party evaluator, Acoura, has set the target reference point for the spawning stock biomass at 20,000 tonnes – an amount that the cod has only surpassed twice in the past 32 years, specifically in 2003 and 2004. Currently, DFO researchers assert that the spawning stock biomass is closer to just 16,000 tonnes. At the same time, a condition of the certification report states that by the end of the third year, it has to be demonstrated that the stock is at or fluctuating around its target reference point. Fuller and the EAC have pointed out that it is unlikely that this target will be met, given the recent declines in stock and the high mortality rate of the fish. Both Fuller and Sinclair also emphasize that a 20,000 tonne target is an exceedingly low measure of sustainability for a fish species that numbered close to a quarter million tonnes just decades ago. From an on-the-ground harvester’s perspective, FFAW believes that the DFO’s assessment of the spawning stock biomass is too optimistic. According to Sullivan, “inshore harvesters are concerned that the stock is in a much poorer state than the models suggest.”

Over the past 32 years, the cod of the 3Ps zone has only surpassed the target twice. Currently, the number of mature fish is approximately 4,000 tonnes below the target of 20,000 tonnes. As well, the 2015 quota for cod in the 3Ps zone is 13,490 tonnes. This is 76% of the target for sustainability, and 89% of the actual number of mature fish. Either way, catching the quota could devastate the cod population in 3Ps.

The likelihood of the cod reaching the 20,000 tonne target seems even more problematic given that the certification process has not decreased the quota in the 3Ps fishery. Specifically, the quota has not dropped from its current amount of 13,490 tonnes – roughly 76% – 89% of the spawning stock biomass, and triple the amount of cod actually being caught in the fishery, which averages around 4,000 – 5,000 tonnes per year. If this quota were actually met by fish harvesters – which it could be, even with the fishery’s “certified sustainable” status – the cod population in the 3Ps fishery could be completely decimated.

Over a 50 year period between 1960 and 1990, the reported landings in the Canadian Cod fisheries (fish actually caught) averaged 50,000 tonnes per year, pointing to a much higher fish population in the past – nearly a quarter million tonnes. During the early 1990s, reported landings tumbled as the Atlantic Cod population collapsed. The target for the 3Ps zone represents a low measure of sustainability, given the health of the overall Atlantic Cod population in past decades.

In spite of these issues, the MSC’s Lugar insists that based on Acoura’s assessment, “the 3Ps cod has so far replenished enough to be managed sustainably, and that the rebuilding plan in place will ensure the replenishment continues.” If this is true, how can the majority of the 3Ps catch be ignored in the assessment process? Why are the targets so unrealistic? Moreover, how can the quota remain at levels that could effectively extinguish the population of an already at-risk fish species?

These are key questions that have underscored the Ecology Action Centre’s objections, which were invoked under the MSC’s formal objection procedures. “It makes no sense,” said Fuller. “The certification and the quota should reflect what is actually being caught, and who is catching it.”

An independent adjudicator in the EAC’s objection hearing, which cost the organization $15,000 CDN to enact, dismissed their complaints last February.

Even though the accreditation process has passed, the question remains: Is the certification of 3Ps a potential trigger for a repeat of the Canadian cod fisheries collapse? Or perhaps something worse?

All of the 3Ps assessment documents, including objections filed by the Ecology Action Centre and David Suzuki Foundation, can be found here.