Malcolm Jolley begins a three part look at Châteauneuf-du-Pape after a recent visit.

Véronique Maret on one of her family’s Domaine de la Charbonnière Châteauneuf-du-Pape vineyards.

[This post is really about the famous red wines of Châteuaneuf-du-Papes. Click here for my previous post about the white wines of the region.]

I had not thought very much about Châteauneuf-du-Pape before I was invited by the Fédérations des Syndicates des Producteurs from the region to spend a few days there last month as part of a delegation of Canadian wine journalists. In my 25 odd years of tasting (ok, drinking) wine, Châteauneuf would have established itself quickly as a desirable category, but would have also been priced out of my own budgets outside of special occasions.

Today, the base line for a conscientiously made Châteunef-du-Pape red in this country is about $60. That could easily be budgeted towards two bottles from C-d-P’s neighbours in the Southern Rhône, Gigondas or Vacqueras, or three or four good bottles of Cairanne. So, domestically, while I consume a fair amount of wine from the South of France, not a lot of it comes from bottles emblazoned with St. Peter’s keys. I figured a chance to go to Châteauneuf would be more than a chance to enjoy some expensive wine, though. I would go to see the land, taste the wines and meet the people and learn what I could about all three. This post is about the terroir, and the next two will be about the wines and people.

Georges Truc and Kelly McAuliffe are surrounded by Canadians taking pictures of galets roulés near Ch. Mont-Redon

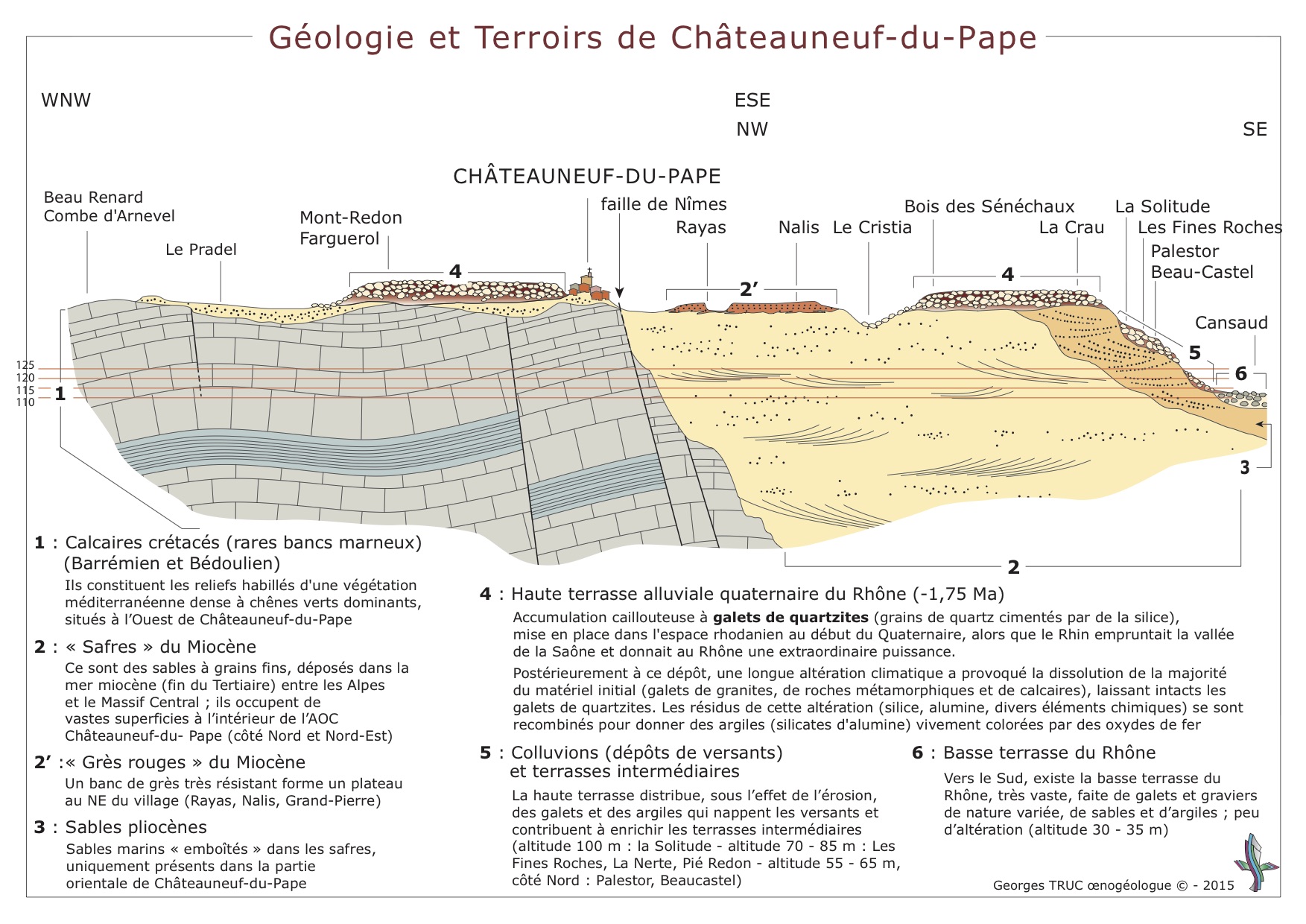

I don’t know if Georges Truc is the world’s only œnogélogue, but he coined the term which is a portmanteau of the French words for winemaker and geologist. Formally trained as the former his area of expertise is the soil composition and geological history of the wine making areas of France. Professor Truc took me and my fellow Canadian wine journalists on a tour of the three main Châteauneuf soil types. In reverse order, with American expat sommelier and Rhône ambassador Kelly McAuliffe acting as translator, we visited vineyards planted in “safres” or sandy soil, vineyards planted in limestone soils with large white rocks protruding, and the most famous (although the least prevalent) Châteauneuf-du-Pape soil, the galets roulés, which could be tongue and cheek translated as the rolling stones.

The galets roulés are an amazing site: fields of sandy coloured river stones the size of a grapefruit or so, with gnarly old bush vines creeping out of them. Comparing all three, there is a general agreement that the sandy soils produce wines with softer tannins, while the stony ones produce more acidity or, that controversial term, minerality. From what I could tell at barrel tastings, this more or less bears out as one would expect it to. But most of the wines I tasted would have been blends between at least two of the three soils, I’m not sure the differences are that important outside of the cellar. Also, I am much more interested in the cultural and human side of wine than its technical characteristics. And what the soils told me was that there was no way anything other than grape vines were going grow in them. No wonder there is a history of wine making in Châteauneuf that stretches hundreds if not thousands of years. That’s what it’s good for.

The galets roulés are an amazing site: fields of sandy coloured river stones the size of a grapefruit or so, with gnarly old bush vines creeping out of them. Comparing all three, there is a general agreement that the sandy soils produce wines with softer tannins, while the stony ones produce more acidity or, that controversial term, minerality. From what I could tell at barrel tastings, this more or less bears out as one would expect it to. But most of the wines I tasted would have been blends between at least two of the three soils, I’m not sure the differences are that important outside of the cellar. Also, I am much more interested in the cultural and human side of wine than its technical characteristics. And what the soils told me was that there was no way anything other than grape vines were going grow in them. No wonder there is a history of wine making in Châteauneuf that stretches hundreds if not thousands of years. That’s what it’s good for.

Sandy soil in the vineyards at Château Nalys with the tower and town of Châteauneuf-du-Pape in the distance.

Châteauneuf-du-Pape was actually the first, appellation d’origine contrôlée, established in 1923. To be redundant the AOC was established geographically, but also geologically and the father of the appellation Baron Le Roy of Château Fortia, decreed that it could only include land that was so infertile that only lavender or thyme would grow on. Le Roy would have, of course, understood that the vine stress endured by the grape plants on such arid soil would only add to the concentration of the wines. Next week I’ll post on what those wines taste like today, at the lab and at the table.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.