A few weeks ago the chalkboard outside my butcher shop, Olliffe in Summerhill, advertized “Hokkaido Lamb”, advising Yonge Street pedestrians to reserve their cuts quickly, as supplies would be limited. What on Earth could be happening, I wondered? Had the Gundy brothers completely abandonned their locavorist activism and begun importing meat from Japan? Google maps puts the distance between Sapporo, Hokkaido Prefecture’s capital, and Toronto at 9,500 kms and change. My curiosity was piqued.

On a later visit I ran into Sam Gundy who explained what was up and what the sign meant. The lamb wasn’t coming from Japan, but from Stirling, Ontario. (Google maps puts the distance between Toronto and Belleville, Hastings County prefecture’s capital at close to 160kms.) But the lamb in question was definitely Hokkaido-style.

Sam explained that among the legacies that Genghis Khan’s invading armies left to Japan are sheep. But, to the Mongol hordes’ chagrin, the only area suitable for lamb in the archipelago was, and is, Hokkaido. When one of Olliffe’s suppliers, Kupecz Family Farm, heard about the Japanese sheep, they contacted Ontario Sake to procure kasu, the rice-based ‘lees’ which is leftover in the tank following sake fermentation. Starchy rice, compared to watery grapes, makes for pretty glutinous kasu, which makes for delicious lamb feed. (Kasu is also used as an ingredient for people, see more on that here.) The Kupecz’s sheep loved the stuff and pretty soon they wanted more kasu than Ontario Sake could send. Now, Sam told me, the Kupecz farm is importing kasu from craft producers across the United States, and had kasu defined as an animal feed to facilitate the border crossing.

The appeal of the Hokkaido lamb for butchers and their greedy customers like me, is a happy animal. There are complicated chemical reasons for the calming effects of kasu on livestock, including the infamous turkey soporific tryptophan. It certainly likely helps that kasu is mildly alcoholic and tasty to the ovine palate. In theory the Hokkaido lamb is less stressed lamb, which should make for a more tender and flavourful lamb.

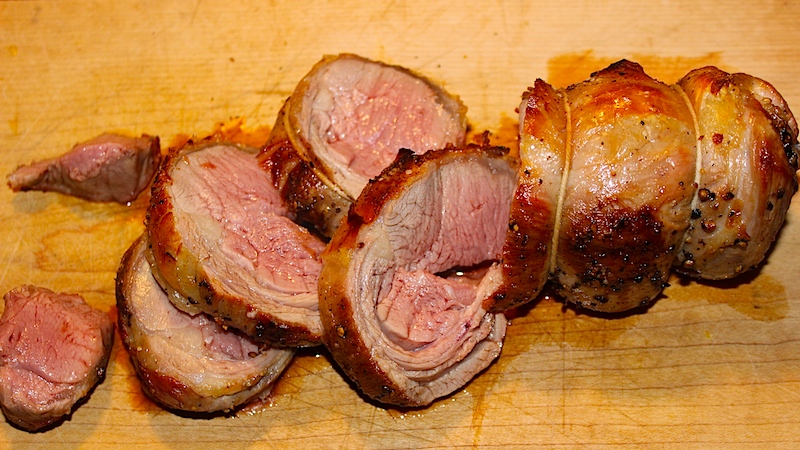

When the first shipment of the Kupecz’s Hokkaido lamb came in last Saturday, I snagged a one pound loin roast. That night, I cooked it quickly to medium in a very hot oven, adding only Rosedale spice (a.k.a. salt and pepper) in order to savour and detect what might make this lamb different from others.

When the first shipment of the Kupecz’s Hokkaido lamb came in last Saturday, I snagged a one pound loin roast. That night, I cooked it quickly to medium in a very hot oven, adding only Rosedale spice (a.k.a. salt and pepper) in order to savour and detect what might make this lamb different from others.

The Hokkaido lamb is different from other lamb, and in an interesting and novel way. I’ll say first off, that it was absolutely delicious and my wife and I devoured the whole roast in a flourish meaty enjoyment. I’ll say secondly that it was also the least lamby lamb I think I have eaten. In this way, the Hokkaido lamb is against the trend of the past decade or so towards grass fed, twangy and gamey meats. The Hokkaido lamb is tender and mild. A decent analogy might be that the Hokkaido lamb is to regular lamb what suckling pig is to pork, or milk-fed white veal to beef. The flavours are rich and subtle, and lack herbal or metallic notes. I paired the roast with a big Rhône red, but I think I’ll try a lighter and more floral wine the next time. Interestingly, the loin was not particularly more fatty or marbled than regular lamb, but it was appreciatively tender.

It’s a rare to find a “new” meat, and I think the Hokkaido lamb qualifies as much, at least in this part of the world. Curious carnivores would do well to contact Olliffe to try it for themselves

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him at twitter.com/malcolmjolley

Malcolm Jolley is a founding editor of Good Food Revolution and Executive Director of Good Food Media, the company that publishes it. Follow him at twitter.com/malcolmjolley

I have used Icewine lees in various preparations for a dozen years to good effect from time to time. They are part of my kitchen larder.

The main use culinary use for kasu seems to be as a pickling agent, according to my very superficial internet research. I guess lees have a relatively high acidity?

I think that the Japanese use them to flavour picked things. Sake seems like a particularly low acid beverage in fact. The fermentation in pickling takes care of the PH.