Wine and Art is an ongoing GFR series on the relationship between the two creative endeavours by working artist and author Lorette C. Luzajic.

The wine list in Mexico is, apparently, simple and memorable: vino rojo and vino blanco.

This was in Cholula, Puebla, after leaving six restaurants that had none.

I was just about to point to the red option when I decided to step out of my comfort zone. So I picked up the lengthy mezcal menu and perused it. Like many wine enthusiasts, I seldom opt for anything else. I know a wide world of spirits exists out there, each with its own unique personality profile and history, but the way I see it, I can’t give another even a sliver of the liver I’ve dedicated to the delectable fruits of the vine.

There in the Zocalo, in a rare ambient quietude in these bustling cities, I sat in the twilight shadows of a handful of luminous yellow cathedrals and a majestic volcano. It seemed fitting, even necessary, to sip wine on this patio as I contemplated all the incredible art and history I had taken that day. But I didn’t want something subpar for such an occasion, and opting for either rojo or blanco meant rejecting the best that Mexico had to offer, which was mezcal.

After last year’s trip to the Rio Cuale in Puerto Vallarta, I touched on the burgeoning winemaking scene (here) and how Mexico boasted the first vineyards in the “new world.” The Spanish wasted no time planting as soon as they could. But production never became the art or commerce that it did in Chile and Argentina, and Mexico remains among the nations that drink the least wine in the whole world.

The locals tell me that’s because they have something no one else does. The agave. Their national drink is, of course, tequila, and why would they want anything else? The blue agave plant is native to Mexico and production for the whole world takes place here.

Way up in Canada, we tend to think of tequila as something nasty to be chugged down, and brought back up later, in vile memories of wayward college days. But Mexicans view tequila as an art, with magicians coaxing a complex array of flavours out of a plant that casts a spell of mirth over anyone it touches.

Mezcal is less familiar outside of Mexico, but the locals know the best spirits come out of the maguey plant, a cousin agave to the blue tequila one. The word “mezcal” is from the Nahuatl, and means “oven roasted agave.” Mezcal is, if you will, tequila chipotle. You’ve probably heard of “fire water” in reference to moonshine or extremely harsh liquors. Legend might trace this nickname elsewhere as well, but when the Spanish ran out of alcohol, they took the pulque- a fermented mash of maguey sap- and sought to distil it for more expedient intoxication. The resulting brew tasted like roasted chiles. Fire water, indeed.

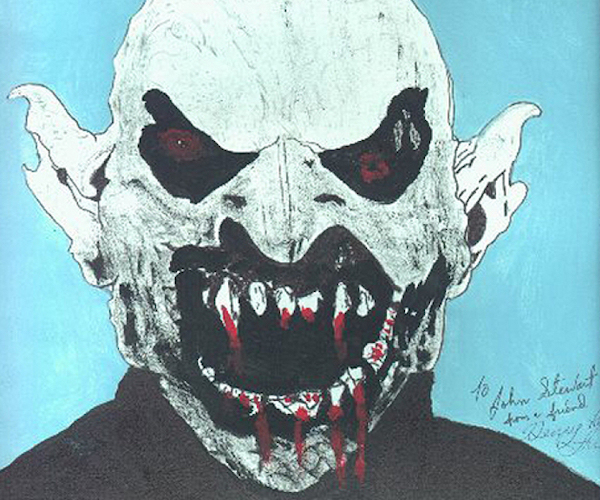

Sipping mezcal tastes initially like inhaling burning embers. It has considerable depth and layers of complexity, and feels like a portal to an ancient world. If you close your eyes and drink enough, you can be transported to another time. Some Cholula natives tell me this perception is not just the fact that I’ve had three already. It’s because the maguey is a sacred plant. Its magic was deeply woven into the spirituality of the pre-Columbian people, who relied on its practical and economical gifts as well as for communion with the gods.

The Mexicas, the peoples who together became the Aztecs, relied heavily on the maguey, as did the people they conquered and sometimes drove extinct. Sometimes reaching an astonishing 40 feet tall, the plant’s fibrous stalks provided tough, durable material that could be used for rope, baskets, in saddles, or to make a shelter. It was used to make paper, like papyrus, only stronger.

The maguey was also used as medicine. As a poultice, it has antibacterial properties that were put to good use by resourceful and smart ancestors. The plant’s sweet nectar, too, was also an important resource, one whose popularity is soaring today all over the globe: agave syrup. In modern Mexico, the agave plants continue to provide employment to countless farmers, distillers, merchants.

The heart of the plant resembles giant pineapples, and that’s where even greater secrets lie. The magic potion, if you will. Legend holds that the gods showed the people how to find them by striking the maguey with lightning. The plant was smashed opening, but also cooked by its brush with fire, and the result was the smoky booze with the bold buzz, the elixir of the gods.

This communion was taken seriously, for it was believed that the gods really entered the imbiber, and it was a dangerous offense to become too drunk. The happiness that resulted from taking in the gods via the mezcal had to be respected. They could not be mocked for their kindness. Recipients were to be duly grateful. To this day, mezcal is sipped slowly.

My friend, who is native to Mexico City, explained that mezcal consumption is still a spiritual act. It is considered a gift to a table of friends. He demonstrated how to sip the stuff and relish its strange, smoky flavours. Mezcal should never be added to other liquids to make a cocktail, he said. Lime is considered by some “training wheels”; conversely, since anything and everything is served with lime, this is too. You sip it slowly. In this way, it is good for everything and every occasion. “Para todo mal, mezcal, y para todo bien, también.” For all that ails you, and for everything good as well, mezcal.

The mezcal does come accompanied by some kind of spice, however. The waiter called it sal de gusano, and I found it quite tasty. Then my friend explained that it was a popular mixture of roasted chili peppers with fried larvae-worm salt.

In many Aztec codices, we see the depiction of Mayahuel, goddess of the maguey plant and mezcal. These codices are themselves often made out of the amazing maguey agave’s fibres.

They say the gods are never far away in Mexico, and just that afternoon I had been to visit the incredible shrine to an unknown goddess, Tonantzil, who could have been Mother Maguey. Today she is Mother Mary. There were many mothers in native mythology, and historians suggest this church was not for maguey, but for the goddess of corn. Regardless, the title Tonantzintla means “our mother” and does not reference a particular deity, but is rather an honorific like “our lady.” Today the mother is Mary. The sign outside the church unabashedly declares that this was the sacred ground of the goddess, and now she is called Maria.

The whole of Mexico is resplendent with beautiful cathedrals, but the Church of Santa María Tonantzintla in Cholula is an unparalleled work of syncretic art in a style we call Indigenous Baroque. It is a veritable explosion of carving and painting.

Every inch of the interior is a mind-boggling panorama of three dimensional patterns and angels. There are only a few churches where the style is manifest, and this one is the most outrageous and spectacular. Indeed, the main purpose of my returning to Mexico was to visit this shrine of human creativity.

It seems only fitting to mark the occasion with the great mother’s milk.

That these sacred grounds may actually harken back to Lady Mezcal is pure speculation on my part, but she was an important deity, so it’s not a totally random stab in the dark either. The collection of pamphlets and websites that I’ve amassed are in Spanish and there are surprisingly few specifics that I have found so far. Maybe I’ll learn the language, or maybe I’ll move on to other art obsessions instead.

It doesn’t matter. The heritage of mezcal and art that I’m so briefly a part of is shrouded in the mists of time anyways. I’m participating in a mystery. This dish of scrambled worms and this peculiar beverage are a kind of magic carpet, taking me a thousand years back in time as I sit silently and relish the Nahuatl and Spanish voices murmuring around me. I also know that I’m romanticizing to some extent, and that the country’s tourists and natives alike idealize the past and its lore. Not all indigenous rites of the past, particularly Aztec ones, were this gentle.

But this one is, and I welcome the warm sensation spreading up my spine. I feel a kind of connectivity to the strangers around me and my surroundings. I’ve entered a mild, dreamy state that I don’t soon want to leave. So I order another, and remember to give thanks.

Lorette C. Luzajic is a Toronto writer and artist. Her collage-centred paintings use mixed media to explore ideas from art, literature, history and culture, always fascinated by the intersection of human creativities. Exhibition of her work is ongoing throughout Toronto, including such venues as the Spoke Club, the Royal Ontario Museum, the Flying Pony Gallery, Toronto Outdoor Art Exhibition, and the Artist Project, and it has been shown in Belfast, Brisbane, Los Angeles, Edinburgh, and beyond. In addition to occasionally writing about her other passions, food and wine, she is the author of more than ten books of poetry, short fiction, and essays, including Funny Stories About Depression, Fascinating Artists, and Kilodney Does Shakespeare. She is the editor of the new online journal, Ekphrastic. Visit her at mixedupmedia.ca. Photo by Ralph Martin.

Lorette C. Luzajic is a Toronto writer and artist. Her collage-centred paintings use mixed media to explore ideas from art, literature, history and culture, always fascinated by the intersection of human creativities. Exhibition of her work is ongoing throughout Toronto, including such venues as the Spoke Club, the Royal Ontario Museum, the Flying Pony Gallery, Toronto Outdoor Art Exhibition, and the Artist Project, and it has been shown in Belfast, Brisbane, Los Angeles, Edinburgh, and beyond. In addition to occasionally writing about her other passions, food and wine, she is the author of more than ten books of poetry, short fiction, and essays, including Funny Stories About Depression, Fascinating Artists, and Kilodney Does Shakespeare. She is the editor of the new online journal, Ekphrastic. Visit her at mixedupmedia.ca. Photo by Ralph Martin.

Wonderful article, very informative, well written, enjoyable, great pix, had a ball reading it and marveled at how close the Mexican ‘stories’ resemble the Pre-Colombian history, shamans, and culture of the Andean nations.