All photos and reproductions used with permission, courtesy of Kim Dorland.

Recently I saw the Kim Dorland exhibition at the McMichael Gallery. After an amazing afternoon with Dorland and the Group of Seven, I’m in the mood for some Canadian wine. The poetry of the occasion calls for something familiar and a little masculine. I choose an Inniskillin Pinot Noir from Niagara, recalling an earthy reliability, a wine that is smooth and just as good in a travel tumbler. The faint notes of tobacco and cherry hit the spot and I begin reading about the show.

I’m taken aback to learn that the exhibition was widely considered a “risk.”

Apparently, cultured, art-loving society is all a-murmur about whether it’s audacious or even profane to exhibit You Are Here: Kim Dorland and the Return to Painting in the ivory halls of high art, corridors sanctified by the likes of Tom Thomson and Emily Carr. Dorland’s art is juxtaposed with the museum’s resident masterpieces. The estate’s majestic pines cradle the very graves of six of the Group of Seven.

For Canadians, this is holy ground indeed.

But the proclamation remains dubious. After all, barely a century ago, a young rogue painter, Dorland’s muse and icon and McMichael darling Tom Thomson, shirked every politesse of well-heeled society. His artwork defied all notions of painting, he was self-taught, and he practiced “en plein air” in the middle of the Algonquin nowhere. I have a hard time believing that these passionate preservers of Thomson’s legacy are under sanitized illusions. Are they really all that shocked by fluorescent splatters, or by “Eminem” carved into a birch tree? I consider Leonard Cohen, Norval Morrisseau, Glen Gould, and conclude that patrons of culture in Canada prefer a little rough and tumble in their genius.

It’s also clear to me that such a show is no risk. It’s a natural, necessary rite of passage for Canadian art. McMichael’s chief curator, Katerina Atanassova, will look back with great relief that she got to it first. After the show, I turned to my date and said, “My mind was just blown. I am always seeking this effect from art but seldom find it.”

In my studio I sit down with a pen and paper. I hope the Pinot Noir will relax me enough to find words to describe why what I saw was so important. In my reading, I notice Dorland dutifully acquiesces about the big shoes to fill. We chat by email later, and he tells me, “I wanted to do something that paid homage to my heroes, especially Tom Thomson, but I also wanted to show the differences in my practice. I made it clear that I didn’t want to be ‘Tom Jr.’ or carry the nationalist torch from the group.”

Dorland’s affinity and all those trees probably do mean being stuck with the ghost of his muse for life. But this will only draw positive attention to his very original work. I jot down other impressions that come to mind, too: Gordon Lightfoot, hockey, the Sasquatch, rock n roll. The ancient wisdom, in vino veritas, seems a distant stranger- I’m seldom at a loss for words, but there’s something more here than, “wow, great paintings!” that I can’t quite get at. An old Neil Young CD is a perfect soundtrack – but for what?

Perhaps what struck me most was Dorland’s love affair with paint. At first I didn’t understand the exhibition tagline, “the return to painting.” I thought Dorland had decided to put his taxidermy away. But the ink is still wet on Canadian Art’s winter issue announcing, “painting has returned to the centre.” I hope the days of piled up concrete bricks or straw bales at the AGO are officially over.

Painting is integral to Dorland’s practice, despite his comfort working with dead deer. It was in 2005 with a painting called The Loner, “when many of my disparate ideas came together… style, material, color and narrative/psychological charge after many years of experimentation. There wasn’t a ‘eureka’ moment, just years of work. I think when I realized that I wanted to tell stories about my life and really push the medium to extremes everything aesthetic came together.”

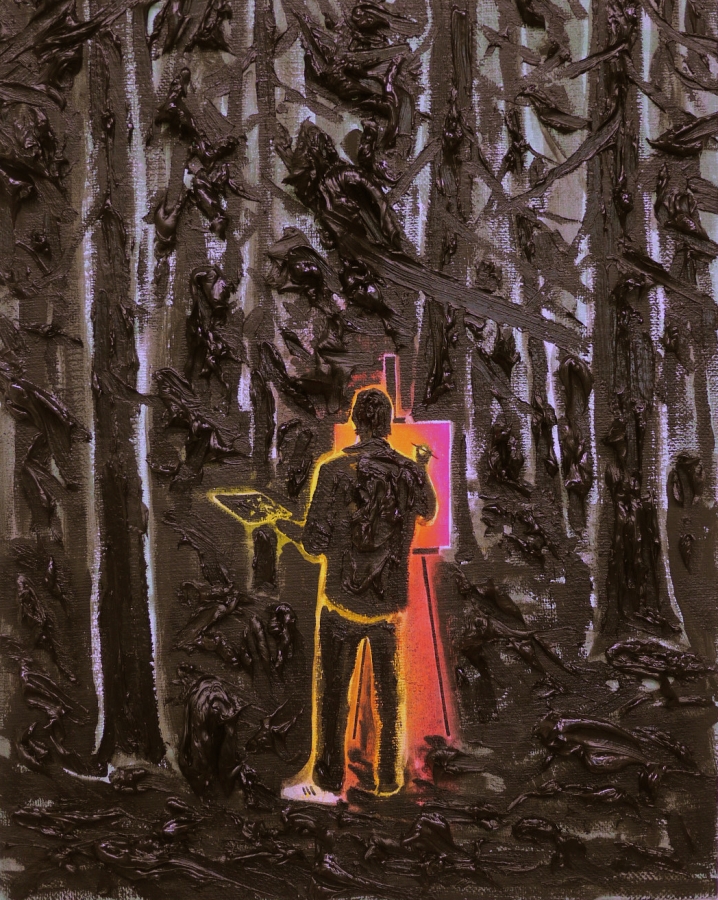

Dorland’s “extreme painting” is gestural- almost aerobic – and involves using massive amounts of paints, creating crazy sculptural effects. The paint is so thick it takes forever to dry and needs to be secured imaginatively.

The artist also wavers between spare, linear, duo-toned pieces and busy, colourful, three dimensional panoramas. He spikes his work with shots of neon. Sometimes he uses colours so horribly wrong they are right. He often works on a dark background and the effects of saturation and exposure are intense.

When I refill my glass, I’m briefly distracted to ponder the joy of Canadian wine on a day of Canadian art. I grew up on Line 6 in Niagara-on-the-Lake, in between rows and rows of grapes, and I’m proud to celebrate a brand new world wine culture. I recall Inniskillin being mentioned in the DK Eyewitness Companion Wines of the World Essential Handbook. It was hailed for leading Canadians away from sweet and fizzy rec room wines toward quality in 1974. The book lists Canada under “other” and aside from mentioning ice wine, out of 663 pages, that was it for Canada.

When I refill my glass, I’m briefly distracted to ponder the joy of Canadian wine on a day of Canadian art. I grew up on Line 6 in Niagara-on-the-Lake, in between rows and rows of grapes, and I’m proud to celebrate a brand new world wine culture. I recall Inniskillin being mentioned in the DK Eyewitness Companion Wines of the World Essential Handbook. It was hailed for leading Canadians away from sweet and fizzy rec room wines toward quality in 1974. The book lists Canada under “other” and aside from mentioning ice wine, out of 663 pages, that was it for Canada.

It is this distraction that lets me connect the dots. Canada’s wine culture is, more or less, just a generation old. We are a young country. A long chronicle of traditions is simply impossible, whether in art or music or gastronomie. Canadian viticulture is new and brash and inventive; its history is kind of rugged and soulful – kind of like Neil Young, kind of like Tom Thomson. There’s a sturdy quality of endurance to the story but it lacks gentility and nuance. A Viking once named us Vineland because he saw some grapes, and then nothing for another 800 years; Burgundy on the other hand has over 1300 years of terroir nurture, beginning with the gentle hands of monks and continuing with royal patrons through today. The grapes of Rioja, Spain, were pressed by foot 2000 years ago, evolving from peasant tipple to today’s prize flagship wine of Spain.

Of course our wines still rely on centuries of the expertise of immigrants’ ancestry from Old World wine cultures; but with them came, too, a pioneering spirit for risk taking and adventure. The terrain here needed to be cleared; and the soil and the vines were brand new.

Perhaps most notable is that the audience itself had to be created. The Francophones of course brought a wine-loving lineage with them, but most Canadians weren’t born with stemware on the table. Canadian culture is still young- the creative, the family, and the social rituals are just being made.

The best young wineries have a new vitality and fearlessness. They were born while still looking for an audience- people who didn’t know about or care about wine had to be captivated. The result? A wine industry with amazing growth, even as consumption per capita in Italy, for example, goes down. New wineries are unencumbered by old shoulds or new obstacles – all they want to do is make wine.

The parallel in the arts is exciting. Italy and France can boast a sophisticated and complex array of cultural contributions from renaissance art to glorious sculptures. But until recent times, we were, most of us, too busy with frontier survival and the taming of the shrubs to cultivate young Mozarts. Now we are burgeoning into a vital and eclectic culture with streams of taste and tradition from all over the world. We are still getting to know our mythologies, merging European concepts of art with the themes and incredible creativity of our native and diverse peoples. While we are in the process of building our cultural identities, we share a beautiful land that gives us greenery and grapes.

This is why Dorland’s work is so important. He has instinctively tapped into beloved markers of Canadiana – the northern lights, the Group of Seven, the moose. But without the technical rigor and the nuances that centuries of Academy training could have instilled, there is a rough-hewn edginess. This is where the energy and originality of style comes from. Unrestrained by tradition, Dorland has invented and pioneered a place for himself. His audience is not alienated from that space. Being affected by his painting is as easy as walking into the woods.

This love of Canada is central to both artist and audience. Still, “There are elements from this show I want to further explore,” Dorland tells me. “But there are also other things I’ve been waiting to turn my attention to. While I definitely have an affinity for Canadiana it’s just one of many ideas that I’m working with in my practice. I don’t like to stay tied down to one idea for too long. I’m lucky in that I have more ideas than time.”

Dorland’s well-known redemption story is worth repeating. A typical Canuck kid, aimless, alienated, going nowhere. Red Deer, Alberta. Killing time was all there was. Kicked out at sixteen. Couch-surfing in a girlfriend’s basement, he opened a coffee table book of Tom Thomson. Now it’s all he wants to do. Art saved him.

In a way, it’s a survival in the wilderness story.

In another way, it’s a finding an identity story.

In another way, it’s our story.

“It is hard now to believe that years ago we who were members of it were regarded as radicals. We were revolutionaries only in that we expected an art movement to develop in our country at a time when most Canadians were indifferent to any form of art…”

A.Y. Jackson

Lorette C. Luzajic is an artist and writer with roots in southern Ontario’s wine country soil. Native to Niagara, at home in Toronto, her work is inspired by wine, cheese, and bleak post-apocalyptic literature. If you missed her at the ROM or the Ritz, visit her at mixedupmedia.ca. Photo: Ralph Martin.

Lorette C. Luzajic is an artist and writer with roots in southern Ontario’s wine country soil. Native to Niagara, at home in Toronto, her work is inspired by wine, cheese, and bleak post-apocalyptic literature. If you missed her at the ROM or the Ritz, visit her at mixedupmedia.ca. Photo: Ralph Martin.

Lorette, I’m blown away!!! I love your writing as well as your art. You are amazing, Love you, Betty xo

Many thanks, Betty. I’m glad you enjoyed the story.