Ever since I first began purchasing wine for a restaurant in Edinburgh way back in the early 1990s, I have had a continual fascination with the wines of Chablis ; from the ever-modest Petit Chablis to wines from the hallowed Grand Cru sites, Chablis is a wine that has certainly kept my palate’s attention throughout the decades. Now I’m not saying that I adore ALL Chablis, as there are some absolute howlers out there, and as the New York Times’ Eric Asimov stated “Sometimes a Chablis can seem too tense, thin and nervous, like an over-caffeinated Woody Allen in a bottle”… quite. I shudder to picture that, as the aforementioned Allen is one of my least favourite characters…

Admittedly I should probably purchase a little more of the stuff for home consumption, but if the truth be told, I’m still not sure that Chablis is for everyone, as many are not as smitten by its inherent charms as I have become. I’ve brought out the odd bottle at dinner parties here and there, and often my Chablis is passed over as many palates gravitate towards the richer and more generous styles of white wine. I’ve eventually come to the conclusion that that to truly “get” Chablis one has to have a basic understanding of what makes the region’s wines so unique, and those thoughts were the genesis of this piece.

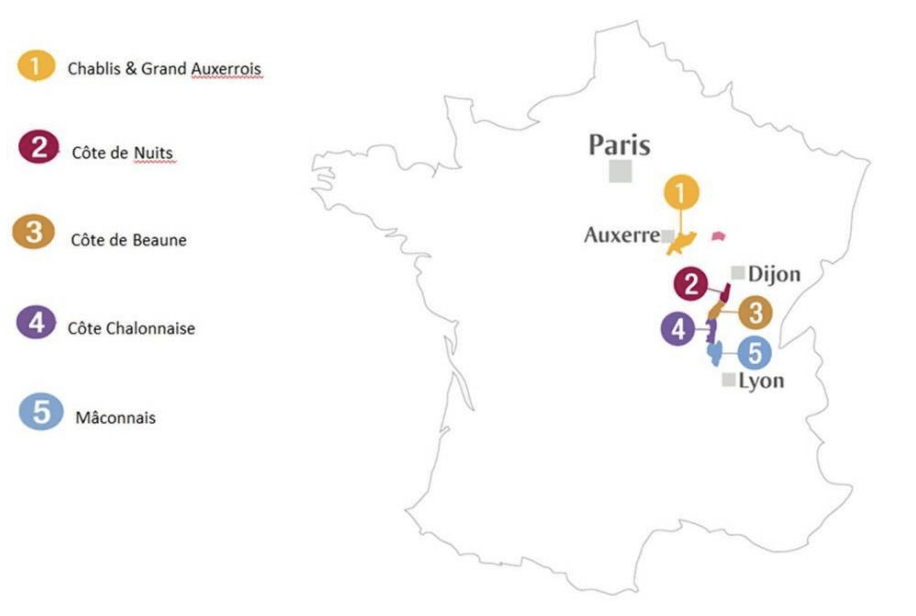

Firstly, I think it’s important to understand the Chablis region’s geographical location in relation to the other four vineyard regions of Burgundy, as well as Champagne just to the north (not pictured on the map above). Chablis is by far the northernmost of the five Burgundian regions, and it can be argued that it is here, and some would say only here, that Chardonnay exhibits its most minerally expressive examples. Although Chardonnay is grown all over the world, I believe that it is in Chablis that the grape finds its true calling.

Although the connection between rock and what’s in your glass is a hell of a mysterious one, it can be said that soils are the veritable birthplace of the complex process that transforms fruit into a vinous image of its substratum AKA the soil beneath the surface.

If one were ever to undertake an exhaustive study of the enigmatic link between stones, soils, and wine, one could find no better location that Chablis, as the region is a microcosm of the entire concept of terroir.

Chablis’ two very distinctive soil types also play a huge part here, with the region being made up of older, chalky, much-more-friable Kimmeridgian soils from the Jurassic era (150 million years ago) with their marine fossils and mineral rich clay, the source of “true” Chablis, and the younger (well, by 2 million years!) and harder Portlandian soils, that are now, for reasons at present unknown to me, going under the Tithonien moniker, where you’ll find all the lesser Petit Chablis, mainly on the hilltop plateaus.

And when we start talking about Chablis appellations it is nigh-on essential to mention the vineyard’s various aspects, as with this being such a marginal growing region, it’s only natural that the most hallowed of sites see the most sun exposure. With this in mind, one can think of the all the 17 Premier Cru vineyards as seeing the most sun, with the rest getting mere Chablis status; the sunniest sites, the superlative sites, being the seven Grand Cru situated on the hillsides just to the north of the village of Chablis and the Serein River that runs diagonally through the region.

It’s probably worth noting here, just in case you were getting confused, that there were some 40 of these Premier Cru sites previously that have now been judiciously amalgamated into the current 17. A pretty smart marketing move if you ask me, as 40 1er Cru just confused everyone, especially as so many of them were so geographically, geologically, and topographically similar, and in some cases named similarly, the end result being that their wines tended to taste pretty similar.

The following gives you a breakdown as to how these 40 climats were slimmed down and absorbed into 17 classified ones (Courtesy of Wikipedia)

- Mont de Milieu – Vallée de Chigot

- Montée de Tonnerre – Chapelot, Les Chapelots, Pied d’Aloup, Sous Pied d’Aloup, Côte de Bréchain

- Fourchaume – Vaupulent, Vau Pulan, Les Vaupulans, La Fourchaume, Côte de Fontenay, Dine-Chien, L’Homme Mort, La Grande Côte, Bois Seguin, L’Ardillier, Vaulorent, Les Quatre Chemins, La Ferme Couverte, Les Couvertes

- Vaillons – Sur les Vaillons, Chatains, Les Grands Chaumes, Les Chatains, Sécher, Beugnons, Les Beugnons, Les Lys, Champlain, Mélinots, Les Minos, Roncières, Les Epinottes

- Montmains – Les Monts Mains, Forêts, Les Forêts, Butteaux, Les Bouts des Butteaux, Vaux Miolot, Le Milieu des Butteaux, Les Ecueillis, Vaugerlains

- Côte de Léchet – Le Château

- Beauroy – Sous Boroy, Vallée des Vaux, Benfer, Troësmes, Côte de Troësmes, Adroit de Vau Renard, Côte de Savant, Le Cotat-Château, Frouquelin, Le Verger

- Vauligneau – Vau de Longue, Vau Girault, La Forêt, Sur la Forêt

- Vaudevey – La Grande Chaume, Vaux Ragons, Vignes des Vaux Ragons

- Vaucoupin – Adroit de Vaucopins

- Vosgros – Adroit de Vosgros, Vaugiraut

- Les Fourneaux – Morein, Côte des Près Girots, La Côte, Sur la Côte

- Côte de Vaubarousse

- Berdiot

- Chaume de Talvat

- Côte de Jouan

- Les Beauregards – Hauts des Chambres du Roi, Côte de Cuissy, Les Corvées, Bec d’Oiseau, Vallée de Cuissy

Whilst the Grand Crus can be really quite remarkable when you get a great one, they are quite expensive, and I tend to find the better values in 1er Cru territory.

It should come as no surprise that vintage means so much in such a marginal region, with cooler and warmer years impacting the resultant wines to such a degree that it can make or break a Chablis wine’s ratings by critics and also its acceptance in the market. As with most established regions, the very best producers are capable of making pretty damn good wines in less than stellar vintages.

Typically fermented in stainless steel to retain all that inherent freshness and acidity, any kind of oak treatment tends to be minimal, with only some 1er and Grand Cru seeing a little cooperage in larger oak barrels, ostensibly to add complexity as opposed to adding any distinctive oak flavours… although I’m sure that we have all heard that old chestnut before… there are some Chablis where the oak is actually pretty apparent when the wine is in its youth, and the winemakers always tell me that this will integrate over time.

One last thought : I do wish that we saw screw caps in Chablis, as I have had more corked Chablis than perhaps any other wine. Don’t let that put you off though, I’m sure that most think that it’s just the terroir… I admit that I did for years and years!

I recently tasted a small selection of Chablis provided by Wines Of Chablis to give you a breakdown of some of what was available:

2015 La Chablisienne “Les Vénérables Vieilles Vignes”, Chablis, France (Alcohol 12.6%, Residual Sugar 2 g/L) LCBO Vintages $26.95 (750ml bottle)

Who says Cooperatives cannot make good wine these days? This occasionally so-so perennial LCBO release sees a noticeable uptick in quality with this warmer 2015 vintage. There’s some lovely ripe Chablis fruit here, but it’s all kept in check by some good mineral acidity, with a superbly persistent finish. All in all this is a very balanced end product. I wouldn’t cellar this one for too much longer though, often the case in those hotter Chablis vintages.

2015 Jean-Marc Brocard “Vau de Vay Chablis 1er Cru”, Chablis, France (Alcohol 12.5%, 2 g/L) LCBO Vintages $39.95 (750ml bottle)

Although I greatly enjoyed this wine, I wasn’t quite prepared for the wine’s more tropical-leaning (not to mention rich) fruit profile, as I tend to prefer a more classic and austere style. Not a bad wine to trick your New World-loving friends with, you know, the ones who would usually find a traditional Chablis a bit too much for their palates. It was still fun to taste though.. and also to pair with… but certainly not one for the purists.

2018 Domaine Laroche “Cuvée Saint Martin”, Chablis, France (Alcohol 12.5%, Residual Sugar 4 g/L) LCBO Vintages $26.05 (750ml bottle)

A very decent introduction to Chablis at a reasonable price, although personally I found the 2017 a little more satisfying than the 2018. Ripe pear, apple, and lemon fill the glass, accompanied by a solid mineral profile on the palate. Although this has all the trappings of a classic Chablis, it’s certainly not going to scare off any newbies to the style.

2014 Maison Olivier Tricon “Montmains 1er Cru”, Chablis, France (Alcohol 13%, Residual Sugar 2 g/L) LCBO Vintages $40.95 (750ml bottle)

I really loved the extra age on this, as the wine had evolved very gracefully with the additional year. Firm acid aligns with broader-than-expected palate, to great effect, as there some real depth here. Really fantastic stuff, and my definite favourite of the four.

Edinburgh-born/Toronto-based Sommelier, consultant, writer, judge, and educator Jamie Drummond is the Director of Programs/Editor of Good Food Revolution… And he thought all of these bottles were showing remarkably well.