Emily Pearce-Bibona takes a look at the two sides of Barolo.

Few wine regions in the world can inspire such heated debate between traditional versus modern innovation as seen in Barolo, Piedmont. Staunch traditionalists see the issue through a narrow lens, while modern, and innovative techniques, as well their resulting styles, have been unfairly lumped and simplified into the modern camp. The divisive, flaming arrow remains the use of French Oak with the Nebbiolo grape. Oenophiles of these beautiful wines have chosen their respective sides in this black and white debate. However, this binary outlook on wines from Piedmont is a far cry from the reality that exists, and what wine drinkers should truly be considering.

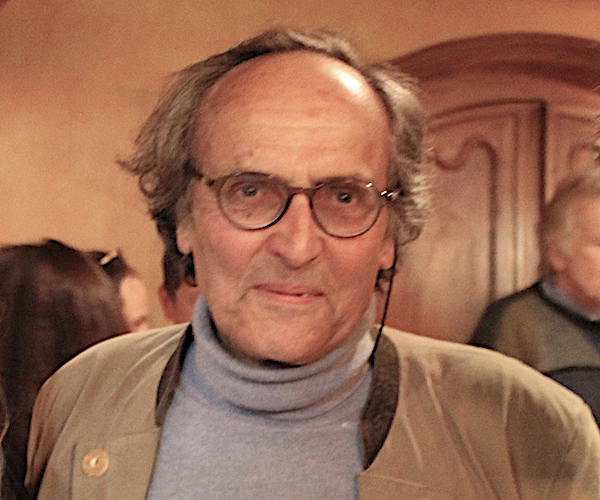

Traditionalism, in the Piedmontese wine sense, refers to techniques used by the founders of the region including long macerations lasting for over 30 days and extended, glacial-speed fermentations with wild yeasts. The wine then settles into an extended hibernation in large Slovenian casks, also known as Botti. Nebbiolo, especially Barolo, was historically considered unapproachable for many years due to the high, rasping tannins and harshness of its youth. Despite this drawback, few wine lovers can argue that Barolo from great producers in favourable vintages are anything less than ethereal in every oenophilic sense of the word, with monumental finesse and intensity. Legends, such as Bartolo Mascarello, Teobaldo Cappellano, and Giuseppe Rinaldi, also known as “The Last of the Mohicans”, championed the traditional ways and passed these techniques and traditional mantras down through the generations. We see winemakers and wine lovers standing in the traditional camp firmly looking to the legacy of these Godfathers even today.

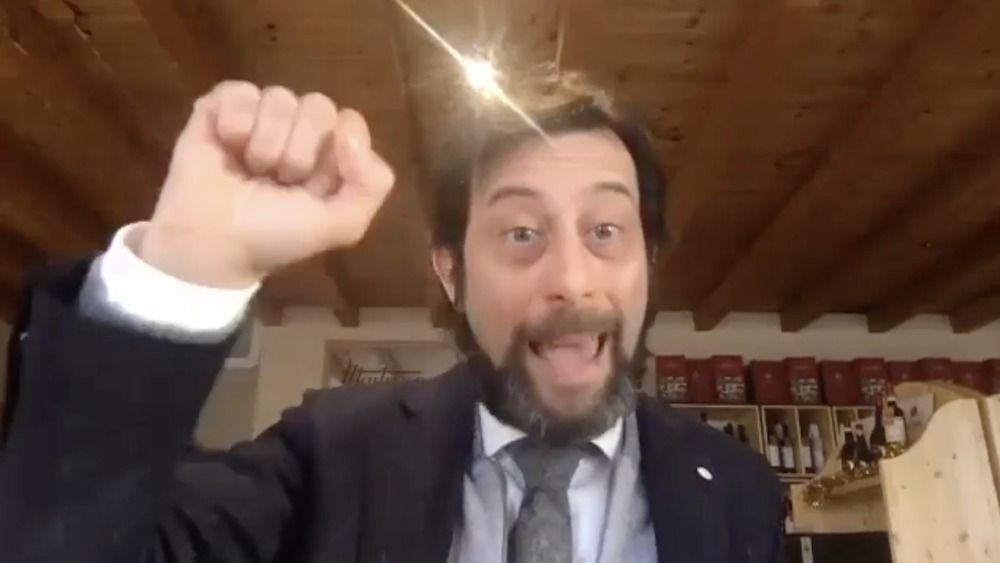

Along came the 1980s and 1990s and everything changed. Outside influence, notably from American critics, took the traditional austere style to task, promoting richer, more fruit-forward styles of wine. French oak notes began to appear, such as sweet smoke, baking spices, and vanilla. Pioneers of the modernist camp, such as Elio Altare leveraged shorter macerations, rotary fermenters, as well as use of French barrels, known as barriques. The wine was lush, bold and appealed to North American palates. The modern movement was so revolutionary that it resulted in Elio being cut out of his father’s will in 1985. Nebbiolo lovers at the time were aghast and continue to be now, as Maria Teresa Mascarello is famously quoted claiming that modern Nebbiolo can be great wine- but it’s not Barolo. However, Elio, and others in the modernist camp stuck by their beliefs pointing out that their wines were not only more approachable in their youth but were also beautiful and worthy of aging.

Considering the two camps from an arm’s length it is easy to pick a side and become a disciple. Most oenophiles remain staunchly in the traditional camp. However, the reality of this dichotomy lies somewhere in the middle.

While new French oak is often derided by traditionalists, there is little denying that when used judiciously it can add attractive complexities to Barolo.

Let’s all take a big step back and consider why we insist on dogmatically defending the traditional camp. The world of wine tends to romanticize the past and staunchly stand by what many perceive to be real winemaking and expression of terroir. We like our wine to evoke romantic thoughts of rolling hills, and picturesque vineyards with storied histories. Much of this is true, but to claim that modernism or innovation somehow robs the soul from wine is short-sighted at best. We often look at wines of the past with unduly rosy spectacles. Modernism, and innovation has undeniably made consistently higher quality wines from friendly Barberas to the great Nebbiolos of the region.

Modernism introduced cultured yeast for use in fermentations. Traditionalists may balk at that, however spoiled, stuck, and incomplete fermentations in the past created undrinkable wines. Temperature control, brought reliable and predictable fermentations as well as safer long-term aging ensuring that wines actually made it into the bottle. Modernism brought celler and winemaking hygiene to the forefront. Strange concepts at the time, however these also mitigated tremendous risks of bacterial spoilage and wines dominated by notes of dirty barnyard. Wine lovers remember the iconic vintages and great wines of the past, but somehow, we don’t remember the spoiled batches or the brettanomyces cellar outbreaks.

Further, why must we insist that there can be no dynamic elements to how we make wine? The craft of winemaking is not static in history. It is a lineage of leaning, and optimizing what nature gives us to make the best wine we can. Does understanding the path of sugar and yeast to alcohol, carbon dioxide and heat, and all the dizzying science behind that, mitigate the beauty and magic that appears in bottle of Barolo? It would be reasonable to suggest that knowledge does not have to stand in the face of tradition. Science does not have to diminish the fact that something beautiful was made. I propose that modernism and innovation in ideal circumstances stand shoulder to shoulder with traditionalism. This is also what the reality of what winemaking in the Langhe is all about today.

The generalization of Nebbiolo, and Barolo living either in a traditional or modern form is grossly untrue. Nebbiolo can express itself in many ways across the spectrum. This wine can be austere, floral, ripe, brooding; the use of French Oak can bring out notes of smoke, baking spices and vanilla as well. More and more you see in the Langhe producers leaving their hang ups of living in the binary world and leveraging innovation and modern techniques while maintaining some traditional ones. Looking at a producer, such as Luciano Sandrone, who uses techniques from both camps, one starts to see that there are no absolutes. Across the Langhe you will find producers using organic and natural farming, and wild yeasts as well as some French oak. The results are beautiful, and long-lived wines that refuse to be defined.

More importantly than trying to fit your Nebbiolo into a binary definition of what Barolo should be, look to what is in the glass, taste the wine, learn about the terroir and winemaker. You may be surprised what you discover.

Emily began her wine journey in Toronto and is now an Advanced Sommelier with the Court of Master Sommeliers. She has worked in top hospitality positions throughout the city. Her passion for learning continues as she also pursues her Master of Wine in the UK. As a contributing writer for Decanter Magazine Online, Emily leverages her knowledge to promote the Canadian wine scene to the world. She is a respected wine judge and most recently was asked to judge the premier competition, the International Wine Challenge in the UK. As the recent winner of the Best Sommelier, and Best Taster in Ontario, she represented the province in the national competition. Emily has had the opportunity to work and participate in the exciting Toronto Sommelier community. She feels grateful to share her knowledge and mentor women in the industry.

Nice article. There is no wrong or right If people are enjoying the wines