Gingerbread Lane, by GoToVan from Vancouver, Canada, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Gingerbread Dreams

“Run, run, run, as fast as you can…you can’t catch me, I’m the gingerbread man…” Traditional Folk Tale

The humble gingersnap was the most important part of the holidays in the world of little Lorette. The confection platters from both Omas overflowed with goodies like almond snowballs, sugary crescent cookies, peppermint ammonia cookies, chocolate pinwheels, thumbprint jam cookies, slices of Christmas stollen, and a festive array of sprinkled and striped candy cane and star sugar cookies that we helped make and decorate. But for me, none of these drool-worthy goodies held a candle to the real deal- the plain brown rounds of gingerbread. “Virgil Grandma” won the duelling holiday bake offs hands down over Niagara Falls Oma.

Since the gingersnap section of the cookie tray was always the first one emptied, I came up with a typically precocious and presumptive proposition- Nana Anna could skip gift selection for me and simply bake an extra gingersnap supply that I could hoard to prolong the holidays. That’s how it came to be that my future presents came in a sturdy freezer Ziploc instead of decorative elf wrapping paper and green ribbons. And if I always loved ornament and tinsel, no matter here: the important thing was that I had an ample gingersnap stash with my name on it. Pure heaven.

Gingersnap Cookies by Jonathan Cohen (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Gingerbread at Christmas, in the form of gingerbread men festooned with lacy icing buttons and snow caps, or flat disks embossed with turbinado sprinkles, or as decorative miniature real estate covered in gumdrops and white icing snow, is a definitive part of the season for many Canadian immigrant communities.

Gingerbread is a longstanding cake and cookie variety throughout a variety of European cultures, including Sweden, Poland, Cornwall, Ukraine, Germany and the Netherlands. It is also an American and Canadian staple, with various recipes filling traditional cookbooks, having naturally come along with us to the prairies, to Niagara and Kitchener regions locally, and northeast USA, to name a few. Gingerbread encompasses a range of treats from loaves to pancakes to cookies, with numerous regional styles and signatures. Its essence revolves around the sharp and spicy ginger, most often softened with sweetness from molasses or honey and blended with complementary spices like cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves, cardamom and pepper.

Gingerbread yields an unassuming and homely brown dough, but the complex, delicious flavour has a bite or snap to it that is highly addictive. Unadorned, hard or crisp gingerbread biscuits are perfection for dipping into tea, coffee, or milk. Virgil Grandma’s snaps were ginger glory- dry for dunking, but chewy when you bit into them.

Gingerbread is perceived as a profoundly European tradition, but ginger itself, the sharp-flavoured and knobby golden rhizome, originated in the South East Asian islands, including Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines, dating back at least 5000 years. Zingiberis, or ginger, the root had various uses in spiritual rituals and as food, medicine, and seasoning, and seafarers moved it quickly to neighbouring mainlands and other islands. It was an ancient food and medicine in China and India, and later, equally a staple in the Middle East and Mediterranean worlds.

With different gingerbread traditions dating way, way back in European history, the introduction of ginger into Europe is tricky to pinpoint. Most accounts say survivors among the crusading soldiers must have brought the notion back with them, and it is true that sweet and spicy cakes of varying sorts provided nourishment for those at war or those wandering long distances. Spices like ginger could help extend the life of a pocketful of sustenance and make the flavour more palatable in hard times.

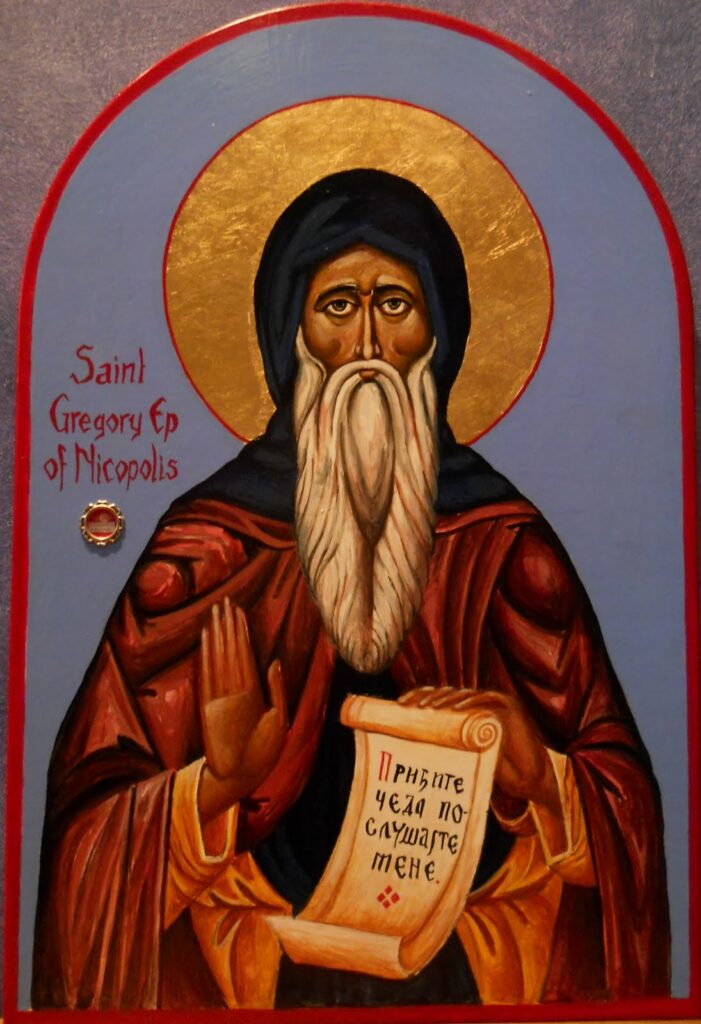

But some records potentially point back further still, to Saint Gregory Makar, an Armenian monk who lived off of edible roots, honey and air. He was chased out by the Persians and ended up in France, where his penchant for spice bread took off in many directions. “Pain d’epice” is an enduring tradition in France through today, and has historically been a version of gingerbread, although many are made with cinnamon and honey.

The problem with this story, however probable, is that it is not the earliest or only story, either. The Greeks and Romans had been enmeshed with Arabia and Egypt through proximity, war, and trade for more than a millennia before Saint Gregory was born, and they prized ginger in their pharmacies and cucinas. Confectionaries made with flour, honey, and spices were already in Greece and Italy, ancestral forebears of gingerbread, at least as close as the monk’s contribution.

Honey spice cakes- a sort of gingerbread- had religious purposes for ancient Egyptians, used in ceremonial burial practices, meant to accompany the dead and sustain them on their way into the afterlife. The specifics are lost in time. Ginger was believed to have ritual, sacred powers including divination throughout its worlds, as well as medicinal and curative properties. Honey was a gift from, and maybe to, the gods, with the power to banish demons and give and take life. The Greeks did something similar, placing the honey ginger and spice cake into the mouth of the dead. Indeed, the first known mention of gingerbread is from Greece, from 2400 BC.

However things evolved naturally through taste and trade, through Europe, one thing is certain- cakes and cookies with ginger were beloved and popular wherever they were enjoyed, and became deeply rooted traditions. In ancient and medieval Europe, spices in general were prized luxuries, with limited availability. Access to the kind of global flavour variety we are used to today was limited. The ginger rhizome had moved widely around the world and into Europe on trade routes earlier than most spices, and its warm, peppery mouthfeel was delicious with savory foods and even better with sweeteners.

Ginger’s distinct and strong flavour could also cover a multitude of sins, disguising old meat or humdrum flour, or giving a kick to plain Jane pastries. There is widespread reporting that ginger was used to cover up spoiled meat, and this is not exactly accurate- rotten meat was deadly then and now. But use of the spice would have helped make gamey or fishy fare, or tough offal, more palatable, and it also helped extend the edible period of various foodstuffs with its mildly preservative properties. Ginger is also famous as a digestive, which would have helped older, blander, and tougher foods go down and stay down. Many sweets made with ginger were considered better long aged, what today we prize as fermented foods.

Gingerbread Market, Konstantin Stoitzner c. 1900?

Gingerbread cookies and cakes were so popular in medieval times that they were staple stall fare at the medieval fairs and night markets. They were frequently made in the shape of animals, birds, flowers, and hearts.

Nuns in different pockets of Europe were baking gingerbread cookies since at least the 1200s, and often monasteries would partner with farmers and merchants of flour and spices. Beloved recipes would become guarded and gingerbread producers in this way became competitive. One way to be on top of the competition was through decoration, as the dough itself was a nondescript dark brown. Round balls, flattened on one side were dusted with icing sugar. These dry dunking dough balls are known as pfeffernesse in German lore- pepper nuts. They had a peppery taste from the hit of ginger, and many included a pinch of pepper, too.

However, this wasn’t decorative enough for everyone. Engraving gingerbread cookie stamps that would imprint elaborate patterns onto cakes and cookies was one approach, or rolling dough with embossed rolling pins. Making cookies became an art form. In other regions, intricate icing was applied as ornament. Some gingerbread was gilded with gold leaf, status gifts among the rich and luxe.

Different regions of Europe developed their own decorative styles for gingerbread cookies and cakes, sometimes to better catch consumer attention or to brand their maker, but also as regional folk art. Decorative traditions with gingerbread evolved regionally the way other arts and crafts did- as ritual, as community, as skill building, as gathering time, as celebration, and to reflect local folk beliefs and religious symbolism.

Because gingerbread cookies could be baked to turn out hardened with lasting edibility, beautiful birds, animals and hearts could double as holiday decorations or giftable ornaments. Hearts in particular could be a gift token of friendship or affection, given to a sweetheart or to a soldier heading to battle. Flowers and hearts and other shapes could dangle on trees, including Christmas trees. The idea of effigies, creating human shapes to represent specific or general people, from saints to celebrities, sprang up in many pockets. Gingerbread ornament cookies were holiday fare for Valentine’s Day and for weddings, for feast days, as well as for Christmas. Creating more elaborate decorations, such as trains, houses, and villages, naturally showed up along the way.

Intricate white piping with icing is so iconic historically that colonial houses from America to Haiti with decorative white lace details are now known as “gingerbread architecture.”

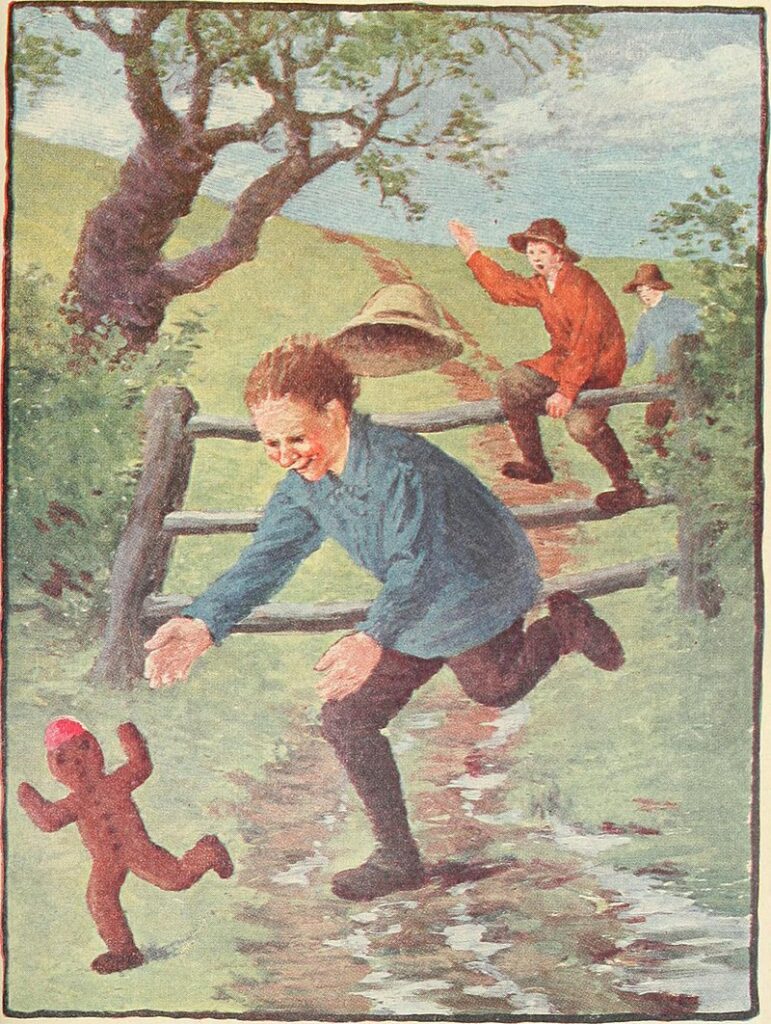

The Gingerbread Man, by Florence Liley Young 1918

The gingerbread man and gingerbread house in folk tales both reflected cultural customs and spawned further trends. The candy house of Hansel and Gretel was not the first German gingerbread house, but when the story was popularized in the 1800s, gingerbread house making became all the rage.

The Living Museum of Gingerbread, Poland (CC BY-NC 2.0)

In Poland, gingerbread hearts and other shapes as well as bricks with elaborate embossing have been made in the city of Torun since the 1200s. Pierniki Toruńskie are a part of national cuisine. Large wooden molds competed for most intricate design, with scenes like a horse drawing a carriage or famous figures. The composer Chopin visited Torun and was so impressed by the gingerbread that he wrote to friends about it.

Russian gingerbread is similar, called pryaniki, with the city of Tula being one famous variety. These cookies are embossed with coats of arms and other patterns. There is a gingerbread museum in Tula that celebrates the heritage.

Hungarian honey spice cookies are world famous for their beautiful red glaze and white piping. They are most often hearts.

Licitar, by Robert Majetic, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

In Croatia, licitar are colourful and wildly decorated cookie ornaments in mushrooms, birds, and other folk insignia. Hearts are the most common motif. Hearts are traditionally given to loved ones to keep, and are not meant to be eaten. They sometimes have a mirror fastened inside the heart, a symbol to “know yourself.” Licitar are for all holidays, including Christmas, and a giant tree covered in licitar hearts is a winter tradition in the capital of Zagreb. Licitar are so detailed that they can take up to a month to make a single cookie!

Germany has been selling heart shaped gingerbread for centuries. Lebcucken were scrawled with icing slogans like “I love you” and “you are mine.” These hearts are an ancestor of the famous message candy hearts we know today.

Lebkuchenherzen_und_Süssigkeiten Oxfordian Kissuth, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

In Sweden, pepparkakor are essential to Christmas celebration. These cookies are frequently baked in the form of horses, other animals, and men and women. Creating festive gingerbread houses is also an important holiday tradition.

While gingerbread replicas of Christian saints and holly jolly motifs abound, like all holiday customs and folk art rituals, older traditions are consciously and unconsciously woven into the histories. Animal cookies are rooted in regional hunting magic and fertility symbolism.

Replica humans were a bright idea of Elizabeth the 1, who made gingerbread cookies to represent her party guests. But the classic “gingerbread man” humanoid cookie outline has roots in an old folk tale about “be careful who to trust.” It is intricately bound in both warnings and ancient ritual reenactments about witches who eat children! The iconic Hansel and Gretel witch who must be outwitted is herself a relic of far older customs. Throughout the world, various ideas about witchcraft include rituals of doing harm to a specific human through the use of an effigy, poppet, or foodstuff. In voodoo lore, sticking pins into a doll causes a pain curse to a living human.

Gingerbread Cookies, photo by Liliana Fuchs via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Gingerbread men were actually outlawed for a time in 17th century Netherlands, because it was feared that witches used them for nefarious purposes. To our rational modern minds, such fears seems preposterous, but they stem from older days still when child shaped biscuits were eaten as symbolic human sacrifice to the gods at Saturnalia. (Think of Goya’s terrible and terrific painting, Saturn Devouring His Children for an idea what this custom reflected.) While the jury is out over whether Saturnalia involved real human sacrifice, actual child sacrifice was real in the ancient world, from Mesopotamia to South America. Saturnalia, of course, is December’s child, the winter celebration. Voila, the ghost of Christmas past, the gingerbread man.

Happy holidays!

“An I had but one penny in the world, thou shouldst have it to buy gingerbread…”

William Shakespeare, Love’s Labour Lost, c. 1595

Antique gingerbread witch, details not known.