By Dick Snyder

I’ve decided I can no longer, in good conscience, rate wines using the 100-point scale.

Or, as I prefer to call it, the much-abused 100-point scale.

So abused that it was become laughable among wine professionals and consumers alike. Or so I like to assert. But I am powerless.

The 100-point score is not going anywhere, now that so many wine writers have figured out how to monetize it. It’s not that I’m against scoring. I do find scores, whether 100-point, 20-point, five stars (or apples), etc. — to be quite useful. But without trying to sound like a jerk, I know how to evaluate them and can discern the shinola amongst the shite. For the average consumer, it’s a mug’s game. The innocent wine lover becomes just another sucker at one big wine/poker table.

This system of rating wines has been pilloried for decades, since Robert Parker popularized the 100-point scale in the 1970s to offer doctors and lawyers a by-the-glance, no-brainer justification to allocate ridiculous sums toward wines they would probably never drink and likely never properly enjoy.

Thus began the race among the elites to collect high-scoring 90-plus (or 95-plus) wines, notwithstanding whether or not the buyer found them pleasing. A cellar full of Parker-sanctified “star” wines came with serious bragging rights. It reminds me of the scene in American Psycho, where the Wall Streeters one-up each other with evermore elaborate and expensive printed business cards. It does not end well.

My problem with the plague of high-scorers that have invaded the wine space is that they offer little to no context for their insane numbers — nor much authority or credibility. They are doing no favours to their followers or readers. An insanely high score accompanied by a breathless, exaggerated and non-sensical tasting note does little to advance the reader’s knowledge, nor provide tangible and useful insight into what makes a wine special — or outstanding, in the pure sense of the word.

It was not always thus, as renowned critic Andrew Jefford points out in the article Tasting Notes: The shame of the wine world?. He states:

“Wine is the most complex substance we put into our mouths in terms of its nuances of aroma and flavour. We have to try to track that verbally in some way or another: simple numerical quantification won’t do. Numbers alone cannot adequately address the mystery of wine’s complexity; words must be involved.”

I’ll discuss the wine tasting note in a future rant. For today, I’ll stick to the topic of scoring. But it’s important to consider the score and the note together, as a score needs a note to give it context. However, a good tasting note can stand on its own in communicating all the pertinent information about a wine. (Emphasis on “good tasting note.”) This is both an art, for you need some writerly flair or at the very least grammatical capability, and a discipline, for you need to discern and communicate the crucial points about the wine that lead to a score or determination of quality.

Jefford references an article from the New Yorker called Is there a better way to talk about wine?, written by Bianca Parker (no relation to Robert, I have to assume). The article begins:

“When the wine critic James Suckling described a Château Haut-Brion in the pages of Wine Spectator in 1992, he needed just a single phrase to sum up the taste: “Big and meaty, with lots of fruit and full tannins, but featuring a sweetness and silkiness on the finish.” At the time, the field of wine criticism was gaining momentum—the magazine’s circulation that year surpassed a hundred thousand—and written tasting notes were moving beyond encyclopedic reference books aimed at wealthy men. When Suckling sampled the same Haut-Brion again—a bottle from the acclaimed 1989 vintage—in 2009, his description of the wine’s flavor carried on for seven sentences, evoking cigarettes, pastries, and saunas in his promise of “perfumed aromas of subtle milk chocolate, cedar, and sweet tobacco.”

Does anyone want to read a tasting note that goes on for seven sentences? Nope. But people who over-score wines — and James Suckling is a major perpetrator — need to justify an exaggerated score with an exaggerated note. Thus, they reach for the thesaurus and aroma wheel, and they mine a little Shakespeare to boot. Sadly, without the Bard’s grasp of nuance, poetry, and brevity.

This is all so dreary and sucks the life out of the joy of wine discovery. I got into wine by reading short notes by great wine critics like David Lawrason, Tony Aspler, and Jancis Robinson. Never more than two sentences, and maybe a score attached. Then, I bought the wines, looked them up in the wine encyclopaedia or atlas, and did the hard work of learning (and a lot of drinking). With the 200-word notes of today, I can’t even get to the end of most of them. I can’t imagine what a newcomer to the wine world must think. Probably something along the lines of: “What a bunch of wankers.”

Too many scorers bestow inflated ratings on wines that are merely good, possessing none of the ethereal beauty, spirit and magic of a truly fine wine. And don’t get me wrong here: a fine wine needn’t cost $50. There are fine wines in the $20s. But there are no under-$10 wines deserving of a 90-point-plus score. None. Nada. It can’t be done. (More on this in a future rant.) Sure, there are “good” wines to be had for $10, though most are merely “acceptable.” But there are no wines that rise into the “very good” level or above.

Nevermind what The Toronto Star’s Carolyn Evans-Hammond or Italian critic Luca Maroni or Suckling — three of the worst perpetrators in conventional media — have to say about it. I used to think Canadian wine critic Natalie McLean was a prime offender, but her scores seems downright stingy compared to this lot. (And she writes well, as a bonus.)

On the topic of scores, Master Sommelier John Szabo wrote this on the WineAlign website a couple of years ago:

“If you pay attention at all to wine scores, you’ll probably have noticed that the numbers on WineAlign are relatively low compared to the impressively large numbers that are invariably attributed to wines on shelf talkers, stickers on wine labels, websites and other marketing material, including the [LCBO] Vintages circular. Believe me, we hear about this frequently from our advertisers.”

This is an important point: advertiser pressure can affect wine scores, especially from wine writers or publishers who have designed a business model around generous scores.

Earlier this year, the Star added a disclaimer to the bio that appears below Evans Hammond’s column, which reads: “Carolyn Evans Hammond is a Toronto-based wine writer and a freelance contributing columnist for the Star. Wineries occasionally sponsor segments on her YouTube series yet they have no role in the selection of the wines she chooses to review or her opinions of those wines.”

Well, that certainly clears things up.

Noting a vicious cycle that high-scoring wine writers fall into, Szabo continues:

“You’ll also have noticed that the numbers seem to be getting bigger and bigger – in the industry we call it “score creep”. It’s like an arms race, with certain reviewers and bloggers engaged in Olympian one-upmanship, attempting to outdo one-another with ever-higher scores. It’s an effort, I’d have to guess, to be that name quoted on the marketing material. Which writer doesn’t want free public exposure?”

Full disclosure here: John Szabo is a friend, as are several of the principals at WineAlign. Notwithstanding, I respect their expertise and the transparency and frankness they bring to wine judgment, as can be seen in their often hilarious and always educational YouTube series titled Think you know wine? (Here’s a link to one of the episodes.) Any wine critic who dares to taste wines blind and in full view of the public — well, hats off. They may as well do it nude too. [Please spare me. Ed.]

I use WineAlign as a reference check against other wine reviewers. Yes, sometimes there can be a point spread of several units when three or more judges score a wine, but they almost always agree on the general quality as being poor, acceptable, good, very good and outstanding.

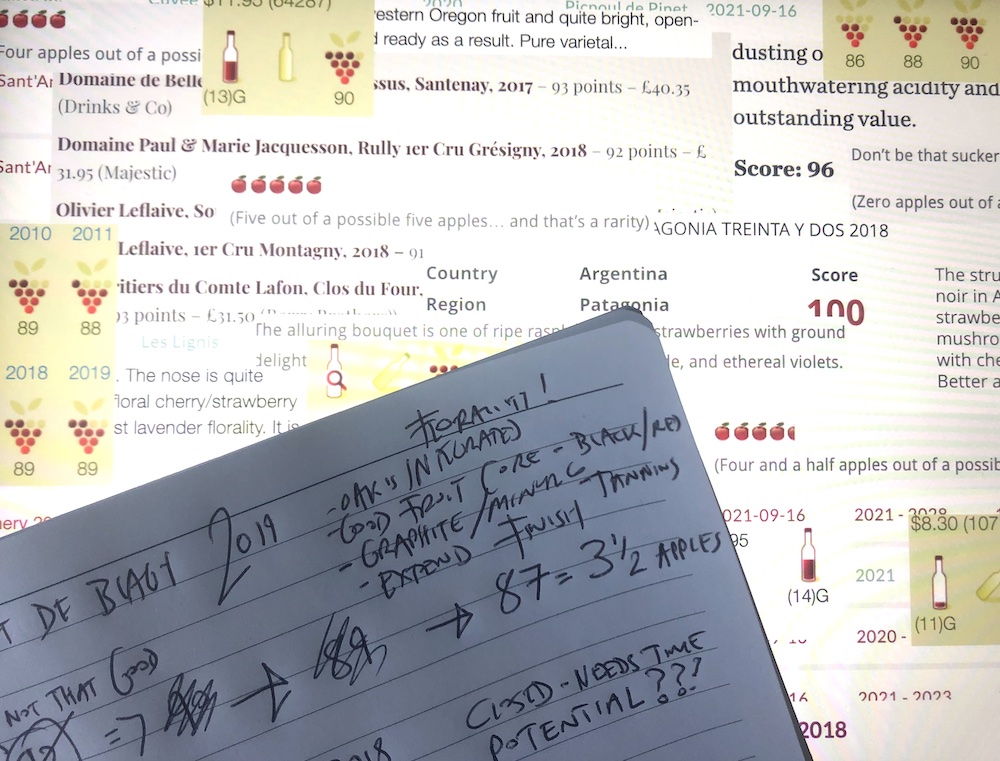

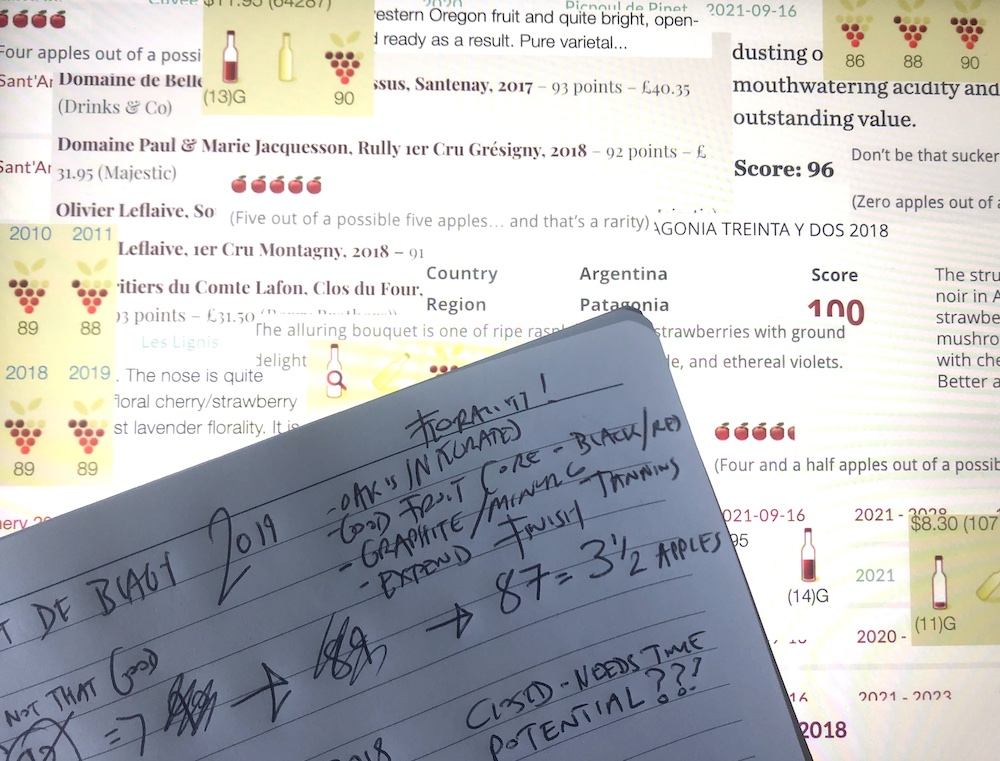

This is the basic system taught at the Wine and Spirit Education Trust, in which we are trained — I have completed up to Level IV diploma level — to evaluate a wine and give it a quality rating. Loosely, this should translate as follows (and this is my own interpretation): Poor = 79 or less. Acceptable = 80 to 84. Good = 85 to 88. Very good = 89 to 92. Outstanding is everything above. We are taught to justify a quality designation based on many factors —most importantly, aroma, taste, balance, etc. Outstanding wines stand above all others for qualities such as concentration, balance, purity, complexity, texture, and potential for aging.

If one were to use a 5-point score or star system, it would look like this: 1 = Poor. 2 = Acceptable. 3 = good. 4 = very good. 5 = outstanding. The system used here at Good Food Revolution by the estimable Jamie Drummond is based on this, using apples instead of stars (just because). The British — Jancis Robinson, Hugh Johnson, Oz Clarke, etc. — generally favour a 20-point system.

Once you get used to how a writer scores, you can judge whether or not you personally agree; that is, whether or not your palates align. I find comfort in the fact that Jancis Robinson very rarely allots a wine more than 17 points.

With most of the insanely high 100-point scorers out there, I’ll lop off 5 to 7 points. When the bottle sticker says Suckling or Evans Hammond gave a $17 wine 94 points, subtract 5 points and you have 89, which represents a good to very good wine. I’m not saying Suckling et al don’t know how to taste wine, they just over-rate them. Once you figure out your own value quotient, you can determine if the wine is worth the money. A good wine for $17 is a fair deal to my mind. So, I sometimes hold my nose and purchase a Suckling-anointed wine, because it just wouldn’t be far to shun them all, would it?

Remember that the score alone is useless in the absence of price and a sensible description (tasting note). Getting back to my own decision not to score wines for public consumption (that is, in articles or on social media), I prefer to write a short note, give the wine some context as to how to enjoy it, and comment on its value, price and what makes it special. I like to use the poor-to-outstanding scale to convey my overall conclusion as to quality. I aim (and often fail) to express clearly and succinctly what is good or noteworthy about the wine.

Whatever the scale and whatever the words used, a wine critic’s role is to give the consumer a firm assessment of quality and some inkling of its main attributes. And not a lot of hyperbole.

This is a key point. It should be easy to figure out from a score and a note whether or not you will like this wine. You are the drinker, the consumer, the one laying out the cash. The wine writer should convey to you what the wine tastes like, not try to convince you that it’s inflated score is justified by using highfalutin descriptors. And they certainly should not try to convince you that the wine is just a few points shy of absolute perfection.

My favourite take on this whole insane mess was written by Hugh Johnson, one of my all-time favourite wine writers, in his indispensable annual Pocket Wine Book. This was in the 2000 version, but I imagine it’s also in the latest edition:

“America is besotted with the 100-point scale system devised by Robert Parker, based on the strange US school system in which 50 = 0. Arguments that taste is too various, too subtle, too evanescent, too wonderful to be reduced to a pseudo-scientific set of numbers fall on deaf ears. Arguments that the accuracy implied by giving one wine a score of 87 and another 88 is a chimera don’t get much further.”

“America likes numbers (and so do salesmen) because they are simpler than words. When it comes to words America likes superlatives. The best joke of 1997 – at least I hope it was a joke – was the critic who came up with a 150-point scoring system. He argued that if 50 was no score at all you needed 150 to reach 100. Logical, but if it catches on there will be chaos. It might just ridicule the whole unreal business to death.”

On that note, I left a comment on James Suckling’s Instagram, noting that if he rates all wines from 90 to 100, then when can we expect him to start adding decimals? I suggested he’ll do it once he’s figured out how to monetize a score of 93.4 versus a score of 93.5. (I don’t think he replied, and I never checked. I’ve stopped following him anyway.)

Here’s a suggestion for the wine lover to avoid the pitfalls of hype. When you’re reading a wine score and note, do what good poker players do. Figure out if you’re being bluffed. Look for “tells.” These might be meaningless adjectives like “perfect” or “ultimate.” Look for ridiculously specific notes like “hints of burnt orange peel with the pith removed and just a dusting of sweet clove spice, leading to a supple salinity akin to the westerly ocean breezes in Mallorca.”

And then do a little math. Here’s a trick: Add the two digits of the score together, and if that number is more than the price of the wine…. Well, as they say in poker, when you can’t figure out who’s the sucker at the table, it’s you.

Dick Snyder’s piece on wine ratings is excellent. It’s almost impossible to buy wine not rated by James Suckling but I discount him and check others as well — e.g. the consumer ratings by multiple Vivino subscribers plus Jancis Robinson when I’m able to access her site.

Thanks, Richard. Yeah, Suckling is unavoidable. I’m not saying his palate is bad, it’s just his inflated scoring. Knock 5 points off just about any review and you’ll have an accurate score that lines up with respectable folks like Jancis, Jeb Dunnuck, Jamie Goode, David Lawrason, et al. I like the WineAlign folks for their insights and realistic scoring. Full disclosure: I edit for their website. I usually find Decanter reliable. Anyway, we’re in the midst of the vinfluencer revolution (insurrection?! hahaha!), wherein the race to over-score the reviews given by others is getting out of control. I saw a 97 point review for a $25 Niagara wine recently. And it’s a solid wine, at 90-92 points. This is why I don’t score anymore for public consumption. People (vinfluencers) and Suckling are embarrassing themselves, and they don’t even know it. I’m a conscientious objector.

HI Dick,

I agree with you on Suckling, although I only discount him by 3 points or so. No need to mention Luca Maroni at all. One thing though, I have to defend the long tasting note – when it is inspired to be a long note. I have been in the hospitality/wine business for over 20 years now (yikes, first time I’ve done the math), achieving my WSET Diploma and getting to taste some pretty special stuff along the way. The companies and people I have worked for have allowed me to taste wines I could never afford if I also wanted to eat and/or make rent, and for that I am thankful. Some of those wines have given me truly moving experiences – and not in the context of tasting with a famous winemaker, or in on a hilltop in Italy, but just around the tasting table or in a casual restaurant. There are a select few wines that have made my knees buckle, that haunt my tasting memories, and I will likely never see or have access to them again. Such is the beauty of wine and I wish everyone could have moments like those. Those wines deserve 7 sentences to me, maybe more. Could Suckling have tasted a just released ’89 Haut-Brion and used a dozen words, then re-tasted it WHEN IT HAD AGED FOR 30 YEARS and had a moving experience – yes. The danger of the long tasting note is it’s abuse, which I agree, is common. But at the same time, I would never discount a review from a writer who is having a true wine-experience-of-a-lifetime, and I’m sure there are writers that have them more often than I do. It sucks that we’ll never know how moved a writer is if they always write in ‘long form’, but if Jefford published a 7-liner would you take it seriously or think Andrew had sold out? If someone who didn’t know Jefford read it, would they write him off?

Suckling is great, once you recognize that he is using an 11-point scale (90-100). Actually, I pretty much just get WS-graded bottles and ignore any JS not on sale. I like your math at the end…implies only a sucker would pay more than $18 for a bottle of wine! This doesn’t meet the 2-digit criteria, but if I could find a 100 point wine for $1, I’d be happy. Would even be happy to pay $1 for a wine graded in the 80’s by JS, but that would be about as rare a find.

Love this article! I wish someone would do a consolidated “score” across all (respectable) critics, weighted appropriately eg JS x 0.95 (in your estimation), JR x 5.1? etc. and then correlate this to its current price* to highlight good buys. Where price = the cheapest available (including shipping) to my home.

Is that too much to ask?!? Oh, and would be good if I could put in eg dislikes (American oak/dill, butter) and likes (anise, higher acid).