What’s a sidecar?

How I learned to evaluate a bar entirely based on its ability to deliver a classic cocktail

By Dick Snyder

Once upon a time in a little town formerly known as York, there was a pretentious restaurant called Rain.

Rain was the hottest shit for maybe 19 days one summer in 2000, until a critical mass of people who had dined there reached a collective realization akin to a “what the fuck” moment. Either that, or someone poked their eye out an insane lance-like garnish and sued the crap out of the Rubino brothers who ran the joint. (No one knows what happened to these two, but you might still find them on Food Network.)

I had my own personal WTF moment within 15 minutes of arrival, when our server looked perplexed when I ordered my favourite pre-dinner cocktail, the Sidecar. He’d never heard of it, and likely suggested a Cosmopolitan instead… “they’re, like, really hot on Sex and the City!” (No, I imagined that last bit. Sadly.)

So I told Deign — we decided to call him Deign, not sure why, but I think it had something to do with his single-strap black athletic-style shirt — to ask the bartender about making a sidecar. “Don’t worry,” I told him, “it only has three ingredients — four if you count the sugar rim, which you can leave out. But if you fuck it up I will kick your skinny ass across Mercer Street.” (I’m paraphrasing here.) The sidecar came, and I remember nothing about it. But given that we stayed for a meal, it was at least good.

About this time — though probably later — I got to thinking that the sidecar might be my canary in the coalmine. A harbinger of things to come, good or bad, when I visit a new bar or restaurant. I’ve saved a lot of money by not dining at — or ever returning to — places that can’t make a good Sidecar. I’ve walked out of a few of them too, after flipping over the table and smashing the barkeep’s phone. (I’m visualizing here… yeah.)

I don’t even require the sidecar to be great — it can be merely good and I will be satisfied. This means a well-proportioned — balanced, that is — drink, served in the correct vessel at the correct temperature. Flavours are integrated, acidity is apparent (and enjoyable) and the texture is creamy-icy. The cocktail is med-full bodied and prominently boozy, and it tastes like a drunken lemon. A fresh, though drunken, lemon.

Last fall, when one was able, for a short time, to visit bars in person, I had two of the worst sidecar of my life at two of Toronto’s prominent bar-slash-restaurant operations. One, a hipster vegetarian joint, the other a swanky hangout for brokers and monetary-policy people. Neither place featured the sidecar on the cocktail menu — which, nonetheless, should never be a deterrent to ordering one. Both places, I would say, comport themselves as true cocktail bars, with the requisite kitschy “custom” cocktails dominating their lists. I’d had cocktails at both places pre-Covid, and they were good. And I realize that restaurant and bar talent became scarce due to the pandemic, so I won’t name these two places here. (Send me an email and I’ll tell you.)

But to continue my rant, a place that purports to be a cocktail bar should have the talent required to make a dozen or two cocktails from the “canon” — the list of foundational drinks from which all others are derived. These needn’t even appear on the menu, but they need to be available to discerning customers. Kind of like ordering French fries, an omelette or a green salad at any restaurant. If they can’t do it, best move on.

At the hipster bar, the bartender required a moment to look up the recipe. The drink came in a tall (Collins-style) glass and I think it may have had ice in it, but I’m not sure. It was vaguely booze and citrusy, with none of the textural supports. It was hardly a sidecar — more of a citrus iced-tea. But it wasn’t unpleasant.

At the suits joint, the entire experience was dismal. The waiter went off to confer with the bartender, and then declared that they would make the cocktail. The drink came in a rocks glass. It was room temperature; it had seen no ice. It was the colour of bile, and it tasted much the same. I left it on the table, and the waiter eventually asked if I liked it. “It is, frankly, not good,” I said. She didn’t seem surprised — and she offered no remedy, and walked away. The drink was not removed from the bill, nor the table. Reminder to self: Don’t drink in a place with TV screens tuned to sports, no matter how swanky.

I don’t remember the first sidecar I tasted. Most likely I read about the cocktail in an issue of GQ magazine. Back in the late 1990s I got all of my advice about how to be an effective man from that magazine. The writing was so good. And I always knew whether to go with two buttons or three, and when the double-breasted suit was no longer a thing. The cocktail advice was similarly on point.

My sidecar epiphany came on a visit to a Relais & Chateaux property in upstate New York called the Old Drovers Inn, a charming place with a storied history reaching back to the 1700s. (And by storied history, I mean that it absolutely involves Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton using it as a clandestine hideaway a couple centuries after its inception.)

I told the bartender, Charlie, that I enjoyed his sidecar very much and he sat with us to chat. This was before my days as an officially designated wine-and-drinks journalist, so my memories are hazy and my notes can’t be found. But if I recall correctly, the cocktail was served on ice in a rocks glass — a very typical Americanization, appropriate to the time. But I knew little about correctness and balance back then, and trusted only that this sidecar tasted fantastic. Charlie explained that the key was fresh-squeezed lemon juice. He told us about an eager apprentice who once squeezed all the lemons into a jug before the night’s service, expecting to be praised for his preparedness. Charlie made him pour it all down the drain. (Can you tell the difference between fresh and not fresh? You absolutely can — more on that later.)

So enough of my musing and pontificating, let’s ask the experts. To test my hypotheses regarding the sidecar as indicator of a bar’s overall ability, I asked cocktail guru and author, Christine Sismondo, for her thoughts. I learned that she’s about to release a new book with my favourite cocktail on the cover. Cocktails, A Still Life comes out in August and is co-authored by James Waller. The “still life” part comes from illustrator Todd M. Casey, whose oil paintings of the 60 cocktails are beautiful and evocative, and will absolutely make you thirsty and want to buy art.

“Although [the sidecar] has a contested original story,” Sismondo explains, “it is absolutely a ‘canon’ cocktail. It’s probably a root cocktail for many drinks that came after it.”

This would include other citrus-based and somewhat frothy drinks such as the daiquiri or the sour. (Note, these may not have technically come after the sidecar, but the style was certainly popularized by the sidecar, which then translated to demand for the sour, etc.) As with most things to do with history, let’s not let facts get in the way of a good story.

It seems the sidecar is celebrating its one hundredth birthday this year, as 1922 was the year a recipe first appeared in print. The Ritz Hotel in Paris is often credited with its invention, but this fact is just as often disputed. David A. Embury’s book The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks (1948) includes the sidecar as one of the six basic cocktails. The others are the daiquiri, the Jack Rose, the Manhattan, the martini, and the old fashioned,

“I think any bartender should be able to make a sour, whether a whisky sour or a daiquiri,” says Sismondo. “They are very important drinks, and they can go wrong in similar ways. Often due to the citrus.”

This needs to be explored — the citrus. As Charlie told me, last century, citrus is key.

I reached out to Massimo Zitti of Mother Bar in Toronto for some insights on the citrus element, and I received a whole lot more. Zitti was recently awarded bartender of the year in Canada by the Diageo World Class Bartender Competition. His bar, Mother, occupies the 16th place on the list of top 50 bars in Canada, as compiled by Canada’s 100 Best Restaurants magazine. Never mind all that, Mother is a damned great place to spend an evening.

The sidecar, says Zitti, is simple.

“It’s so simple that many people forget: You need to use fresh juice. A sidecar or daiquiri, must be lime or lemon, and I will squeeze it by hand. This is my first step — and then the quality of the Cognac… Courvoisier or Hennessey will make a good sidecar, for sure. Some will use sugar on the rim, but I don’t.”

The sugar rim… oh, a whole other can of worms. Zitti is not opposed to it, but it needs to be considered as part of the overall experience. For example, one could choose to increase the acidity of the cocktail, and add the sugar rim to balance the experience on the lips.

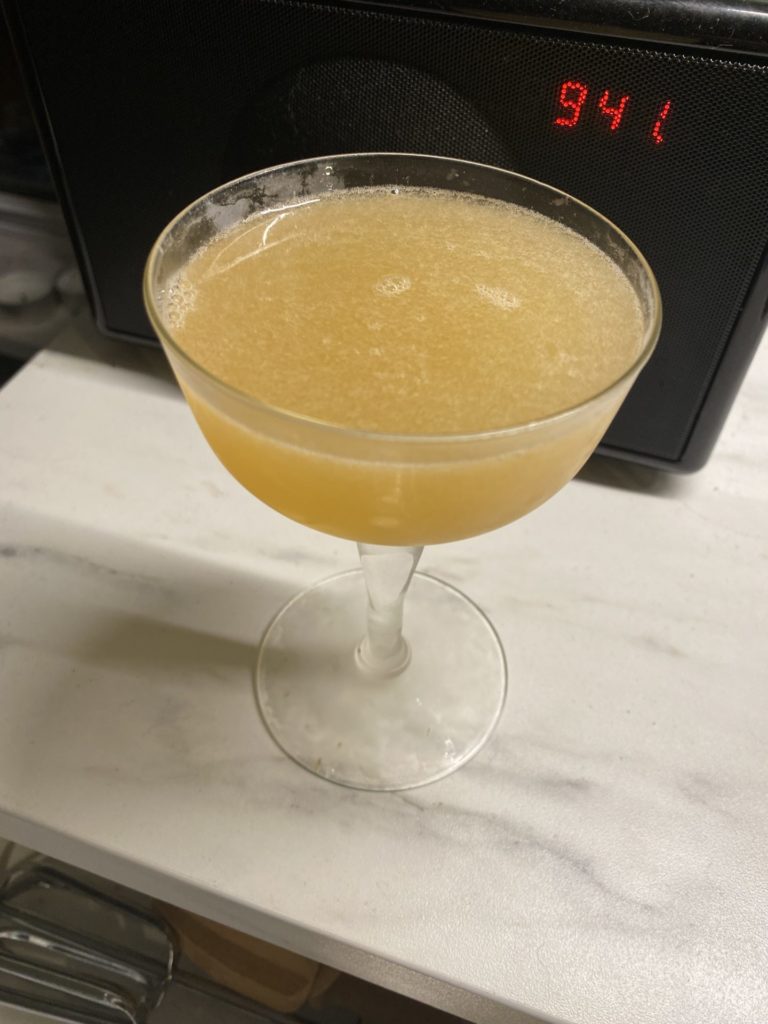

A sidecar from Mother.

The sidecar I had at Mother tasted like a classic cocktail, which I was not sure I would receive when I ordered it. I asked the server: “I’d like your riff on a sidecar.” This request was not questioned. What arrived was entirely a sidecar, served in a coupe at the correct temperature. The texture was excellent. Balanced, complex, delicious. I asked the waiter if there was anything “different” about it. He said that it featured cascara… coffee skins. So I had to go back to Zitti for insight.

On the phone with Zitti:

Me: That cocktail was classic. Very good.

Zitti: I like to use 1.5 ounce or 1.75 ounce of Pierre Ferrand… it’s an orange curaçao, a triple sec. [Official name: Ferrand Dry Curaçao.]

Me: What else?

Zitti: The better the cognac, the better the drink. But before that, we have to tick the other boxes. Fresh juice, a cold glass… it’s a simple drink, but very hard. There are many questions. What ice are you using? How cold is the glass when the drink is poured? How cold is the glass when it reaches the lips of your guest? I would never dare to do too many things to a sidecar … why would you cover it up?

Me: So what about this coffee skin? What else might you do?

Zitti: I like to increase acidity. We have salted honey, and I like to use that. Honey and Cognac is a beautiful combination. Once you increase the sour notes and the volume of liquid, you can go higher on the Pierre Ferrand. I’m saying maybe 2.5 millilitres of salted honey. We also use toasted wild rice syrup — Canadian wild rice, toasted, chilled, blended with maple syrup, salt and light brown sugar. I also like to use a half once of herb de Provence cordial, with orange zest. Or we’ll use coffee absinth. It’s nothing like the original recipe, but you want to twist it using your knowledge. And once you know things, it’s easy to make a twist.

And then Zitti hits on the crux of the issue — my pain point — and what bartenders need to know about cocktails.

“Understand the flavour profile, understand the simplicity…. It’s the hardest thing to understand about cocktails.”

Or about anything. Master the fundamentals. Do it properly. And then, you can go wild.

Richard Snyder’s sidecar.

After talking to Zitti, I broke out my crappy shaker and a bottle of Remy Martin VSOP, a bottle of Meaghers Triple Sec (the basic stuff you’ll find at any LCBO), and a lemon. One point five ounces of each juice. I shook it all up while listening to live AC/DC. I poured it into a chilled coupe. It was great. I could have opted for Premier Cru Grande Champagne Napoleon Cognac and Grand Marnier… which might have been even better. Maybe better, I dunno.

So if even I, an idiot wine writer, can make an excellent sidecar, what’s stopping the rest of the barkeep world?

Sismondo says the issue may be that people come into the industry without a solid foundation in how (and why) these “canon” cocktails are to be revered and studied. Maybe they have a passion for bartending, or maybe not. But they end up behind the bar and are given a set of recipes — those “custom” cocktails every hipster bar proffers — but no foundational instruction in how to make and balance a good drink.

“You learn recipes instead of principles,” Sismondo says.

And there it is. Running before you learn to walk. And why I’ve had to endure so many terrible sidecar.

Sismondo’s recipe, the one that appears in her new book, is simple. Based on principles.

The Sismondo Sidecar

1 ounce brandy

1 ounce Cointreau

1 ounce fresh lemon juice

orange twist

Pour all the liquid ingredients into a cocktail shaker, over ice. Shake for 30 seconds and strain into a coupe or cocktail glass. Garnish with the orange twist.

She notes that some like to double the brandy… aka, the English style. (But, I mean, who would ever trust the British?)

Last December, shortly after I’d had two of the worst sidecar experiences of my short life, I went to Canoe for lunch. Canoe is an Oliver & Bonacini restaurant of much regard, located on the 54th floor of the Toronto Dominion Centre. I’ve never had anything less than a very good experience at Canoe, and I hold their chefs Ron McKinlay and corporate executive chef Anthony Walsh in high regard.

But I wasn’t visiting the restaurant in order to evaluate it. I needed to erase some horrible memories.

I said as much to the bar manager, Jeff Sasone: “I’ve recently had some terrible sidecars. Could you possibly make me a good one?”

And he did. It was outstanding.

In an email, Sasone later explained:

“While the sidecar is not currently on our cocktail list, it is definitely one of my favourite cocktails to make and to suggest. I would definitely consider it a niche cocktail and am completely surprised that the current wave of cocktail enthusiasts — that exploded during the pandemic — have not discovered and embraced it.”

He continues: “When made properly it is one of the best, well-balanced libations out there.”

And here, we talk again about the lemon.

“I think one of the biggest mistakes that some bartenders make is that they use lemon bar mix (which contains sugar) as opposed to the fresh lemon juice that this classic cocktail requires.”

The Canoe Sidecar

1.5 oz Cognac (we use Courvoisier VS)

.5 oz Cointreau

1 oz fresh squeezed lemon juice

dash of agave nectar

Sanson says: “We serve ours shaken over ice until ice cold, strained into a coupe glass and garnished with one of our house dehydrated lemon wheels. I can’t stress enough how important a proper glass and well thought-out garnish is. You could make a perfect sidecar but if you are serving it in an improper glass with a dried out, limp lemon twist, it will definitely not enhance the guest’s experience.”

There’s just one more thing: the shaker. Zitti doesn’t use a conventional two-piece, he prefers the Japanese three-piece shaker.

“When I moved to Canada, they said no one will ever use this in Canada. It’s a very different shaker. There’s less aeration, the ice breaks up more. It’s used for classics like daiquiris and sidecars.”

Zitti is not above being unconventional — that is, after mastering the principles. That’s when, he says, real creativity in cocktail making begins.

“Fuck the specs, man. Nobody cares about the specs… When you are a professional, it’s called improvisation. Like Keith Jarrett, the most impactful of jazz musicians. To be free that way, you’ve got to have the knowledge. So you are sure of yourself and what you are doing.”

Lovely article Dick, I know what cocktail I’m making myself this evening after work! Thanks!

I’m old enough to remember Rain and the “reign” of the Rubino brothers. It was very surprising to me a few years ago while sitting in the renovated food court at Sherway Gardens to see the Rubino brothers working on opening a new fast food pizza place. I was kind of shocked. Unfortunately, Covid came and the place is no longer.

Hi, Tonia! Glad you enjoyed. It’d be interesting to see what the Rubinos would do today. I remember some rather hilarious stories from back in the day, like when Jacob Richler tried to review the place they had for a short time in the Germain Hotel. They kicked him out, so he got a room at the hotel, ordered their room service, and reviewed it… you can guess the rest.

Dick, I was with you at Rain that night. First time we met and first time I’d heard anyone order a Sidecar. I see Guy and Michael in Kensington Market sometimes and they are as busy and charming as ever.

Your memory! Did we actually dine together or just meet there? What are the Rubinos doing in Kensington? I haven’t heard tell of them for a way long time.

Thanks for a great read, Dick! I might adopt this measuring stick for bars myself. It’s a perfect benchmark. This year I started making some cocktail art in the form of NFTs and started with a series of one drink with each of the 6 base spirits – for my brandy drink I went with the sidecar. Not only is it one of my favorite cocktails, it’s also my favorite one in this first series. Whether or not you’re interested in buying an NFT I hope you like the art better than the version you got in a Collins glass!! 🥂 https://www.cocktailicons.com/home/series-1/sidecar

Completely depressing when an establishment cannot make a proper sidecar. I prefer 1738 cognac, grand marinerand fresh lemon juice. Optional garnish of cinnamon sugar or ginger sugar.