This is a column about drinking and about (not) travelling and about terroir. It is about my journey to the Court of Master Sommeliers Advanced Exam and about the wines and beers and whiskies I taste along the way.

If you love wine, and especially if it is your work, the Côte d’Or in Burgundy is the Holy Land. This small stretch of land, this golden slope, is the golden mean by which we measure every other Chardonnay and Pinot Noir made in the rest of the world whether we like it or not. The wines that come from these fragmented parcels of vines can be by turns utterly sublime or horribly insipid. They are never cheap. Which means that they are also perfect engines of desire, leaving you wanting more, seeking to recapture those singular highs, whilst simultaneously leaving you pliant and suggestible because you are terrified of getting it wrong.

Burgundy is the place where the concept of terroir is most often elaborated. Vineyards which lie a metre apart are considered entirely differently from each other. Long ago, so the story goes, monks tasted the dirt here in order to select the best sites to plant their vines. Known as Cistercians, after their new monastery at Cîteaux just north of Beaune, in the heart of the Côte d’Or, they were an agricultural, working order; strict, austere, fervent, and expansionist. Initially a small group of young, rich, and zealous men who took to wearing white instead of the usual Benedictine black, it’s not difficult to imagine them gabbing handfuls of dirt, sticking it in their mouths, and ruminating, nor that this reverence for the soil continues to permeate the Burgundian imagination.

If terroir is a sense of place, then there is no place where it could possibly signify this more than in Burgundy. Is it possible to identify the very slope of a hill in liquid form, to be able to say a wine is from this village and not another? Does one have to be intimate with the combes and the vineyards, the little village roads and low stone walls, the seasons and weather of a leaning Côte d’Or sky, to sense the terroir of a wine?

It is said the magic of wine is to be able to transmit a sense of its origins to the imbiber like no other thing we put a price to. It can transport you back to a place you have been, conjuring memories of a particular time and place. Or it can send you, the untravelled sommelier, who has never set foot on the Route des Grands Crus, to a place you have never been, but have explored hectare by delicious hectare through a vinous map.

Recently, I had the opportunity to explore this vinous map in a tasting put on by the Bureau Interprofessionel des Vins de Bourgogne and led by Master Sommelier John Szabo. John is an urbane and erudite speaker and one of the leading lights in the world of wine, here in Canada as well as abroad. Principal critic at Wine Align, his highly anticipated book on volcanic wines is due to be published later this year. Szabo’s considerations on thorny subjects, such as minerality, natural wines, or most recently, the VQA regulations, are some of the most incisive and balanced found anywhere.

In the brilliant new tasting room at George Brown College filled with some 30-odd sommeliers – students, practitioners, and teachers of wine, all – there is a strange charge in the air, as if things are about to get really serious. As Szabo says,

I’m probably the most excited person in the room here. This is a really rare opportunity to taste a range of village wines and talk about what we always love to talk about, which is to say, terroir and regionality and village expression in the case of Burgundy. Will we be able to tell a Santenay from a Morey-St-Denis from a Puligny-Montrachet, etc, etc.? We’re going to find out today.

We’re tasting blind; we’re looking to identify characteristics more so than the specific village. If we can get that far, fantastic. I don’t expect we will. I’ve tasted through the wines, they are the best representatives that we were able to find from each village but nonetheless there is the human factor that intervenes and that sometimes overrides any sort of classic village character, if there is such a thing.

It’s rarely spoken about but almost universally acknowledged that people are a part of terroir, that the winemaker, the vineyard manager, have a hand in defining the terroir of a given wine. Every winery website can be relied upon to divide their content between people and the land. But the history of a family of winemakers can be no less a part of the terroir than the actual soil. In Burgundy, somebody has to do the Sisyphean task of bringing eroded soil back up the hill. One could not imagine describing the terroir of the Douro valley without reference to their famous terraces, shored and excavated by hand, or indeed Howell Mountain in Napa Valley, cleared of trees and planted with vines.

The human factor is not just the vineyard landscaper, though, it can also be found in the winemaker’s thumbprint and it is just as inescapable as a shadow (an absence of intervention also speaks volumes.) Some winemakers talk about their wine like it is a window looking out upon the land the grapes were grown and that their goal is to have as clear a pane of glass as possible, to frame the land with a drink. But the metaphor is misleading. Wine is not a window; it is a crystal ball through which we can only dream and imagine.

Szabo gives us fair warning, “In fact, maybe the right answer is the wrong answer. I say this quite often with blind tastings. There are some wines that if you actually get the origins right, you’re dead wrong because it’s a totally atypical example of whatever the region is we’re talking about.” Dreamers have their own particular visions.

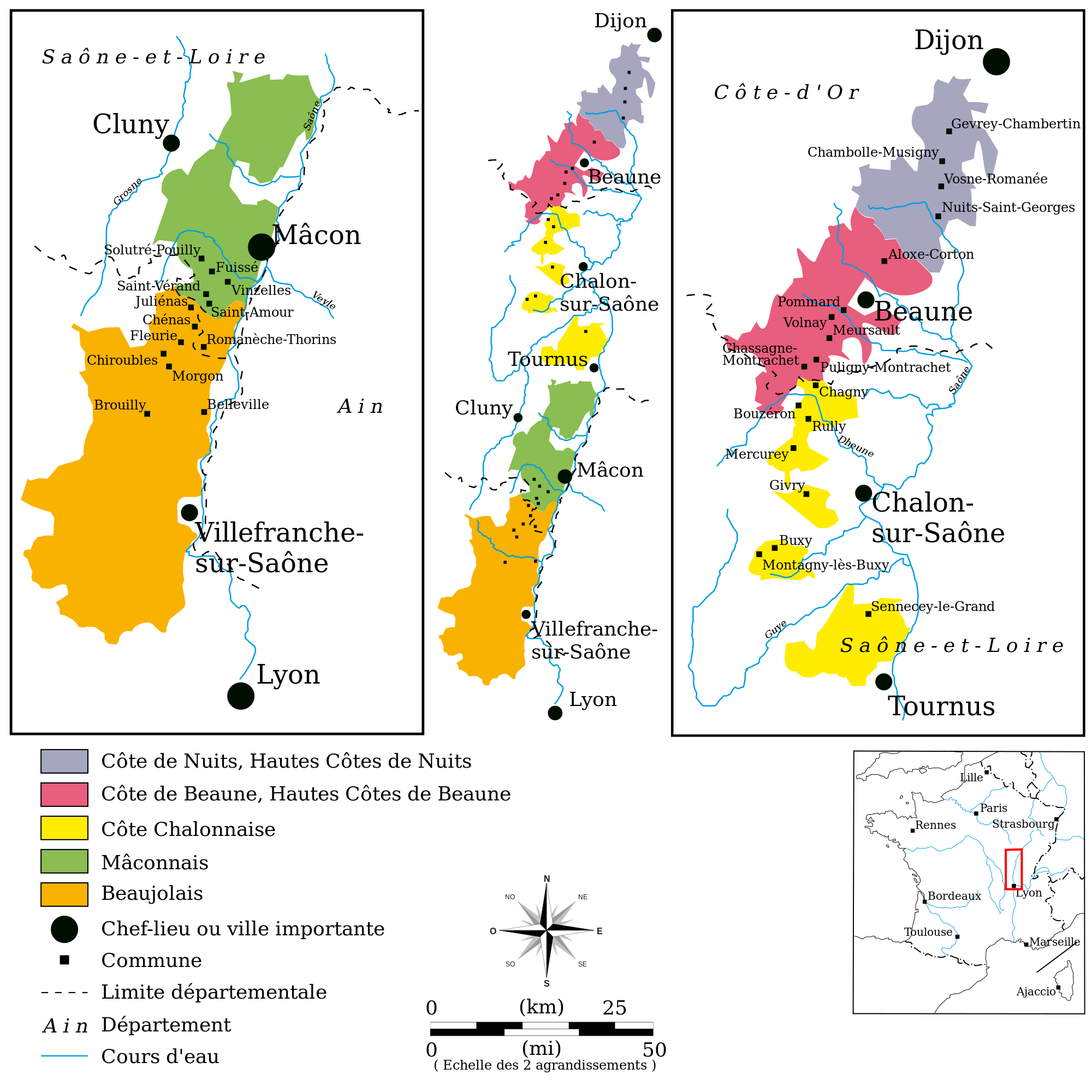

19 wines from 19 different villages in Burgundy seems like a bewildering task to sort out. We taste in flights of white and then red, and Szabo takes up each tasting note given by each sommelier in turn, teasing out the defining characteristics of each village wine.

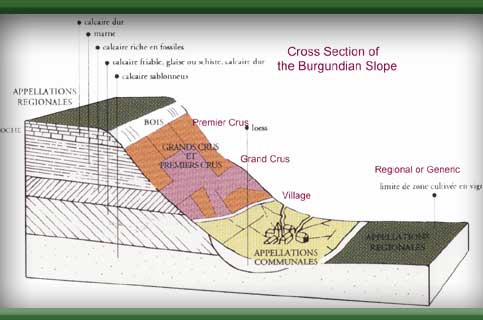

We already know some clues from the soil: limestone and Pinot Noir go hand in hand; while Chardonnay likes marl. This corresponds also to the soil profile of the Côte de Nuits and Côte de Beaune, which is why, very generally speaking, we think of them in terms of red and white wine, respectively. Red Côte d’Or can be further generalized as showing more red fruit in the Côte de Beaune and more black fruit in the Côte de Nuits, though of course, there are always exceptions.

Any discussion of terroir cannot avoid the topic of minerality as it is so often deployed in the elaboration of the concept. But what exactly is it? Does it come from the vineyard or from the cellar, that is to ask, does it come from the land or from the winemaking? Are these two areas, the vineyard and the cellar, appreciably distinct when it comes to discussing terroir? For me, minerality is most definitely a perceptible quality in wine, but what we are perceiving is more likely to be a combination of acids and sulfides (I do not mean added sulfites; sulfides are produced during fermentation) than the mineral content of soils transferred through the grape. That is, minerality for me comes from the magic of fermentation and not the magic of the living plant. Both are living processes and one is no less magical than the other simply for occurring under the guidance of a person.

Szabo explains the difficulty:

Chemically speaking, what that brings to the vines is still a bit of a mystery. You’ve probably read, researched a little bit on minerality, a term that’s been in the press a lot in the past few years, and what relationship there might be between soil chemistry and wine chemistry, and the reality is that we can all taste it, it’s there. I’m not saying it’s not there, we just don’t know what it is. And to parse out all the variables is really tough. When you start looking at all of the micro-variables involved in what’s finally in your glass, obviously climate is a big one, but not just general climate, macro-climate, meso-climate, micro-climate, rootstock, clone type, age of vines, depth of soil. We have one vineyard, but over here you might have 3 feet of topsoil and over there you might have 1 foot of topsoil. Does that impact on the vines? Of course it does, probably even more than the chemistry of those layers of dirt that you have. I believe in it; I just can’t explain it to you.

But Szabo has recourse to a quote from the managing director of the La Chablisienne co-op, to help sketch out the organoleptic appearance of minerality:

For Monsieur Leclerc, ‘those first big raindrops that fall and dry just before a storm on a hot, dry day’: how many of us have used that description to describe whatever minerality is? ‘That sudden refreshing sensation that invades the atmosphere, while at the same time there is tension in the air. A sort of energy, like before an earth tremor.’ I don’t really know what that’s like, but I’ll go with him on that one. ‘Minerality also exudes a certain form of purity, a crystalline expression of the wine’ – all very vague terms, but all very Chablis. Do we really need to know exactly what causes that or can we just revel in the flavours that that gives us? I’ll go with the latter.

Andrew Jefford in a recent column for Decanter (December 28, 2015) writes about the ‘dream force’ of a wine, “the ability to induce reverie, to inspire aspiration or hope, and to promise (even if it finally fails to deliver) exceptional sensual gratification”. This dream-force as described by Jefford has three particular elements: the emotional, design, and the cultural. The emotional depends principally on the effects of alcohol and how we imagine and relate to the personality of different wines. The physical design of labels, bottles, and closures, constitute the element of design. I would also add the marketing of wine to the design element, more straight-forwardly understood as the manufactory of dreams. Finally, the cultural element, the shared Western tradition of intoxication, according to Jefford, is also historical, it is Napoleon and Pepys, it is the dream of judgments, from 1855 to 1976. We dream when we taste. This other sense beyond that of sight, smell, taste, and touch is rarely acknowledged, but imagination can play an important part in the pleasure we take from wine. I drink the wine and I imagine.

We dream of terroir, and we do so in a platonic sense according to Jefford:

I’m loathe to admit it, but the notion of terroir also has as much to do with wine dreams as wine reality. Is every bottle of Sancerre signally different from every bottle of Pouilly-Fumé? Of course not, but the dream of place insists we think about them in a different way, and insists that both are different to Sauvignon de Touraine. The dream, here, is a kind of ideal, like a morally perfect life, to which all must aspire even if few end up conforming.

The shadow on the wall would nominally be the glass of Sancerre in your hand and the ideal would be the idea of the perfect Sancerre. But, in fact, it is the ‘dream of place’ which is the shadow-play in your mind, your imagination of the perfect Sancerre or the perfect Morey-St-Denis. As wine professionals, we are always doing this, measuring the liquid in the glass against an ideal tasting note, what we believe this wine should be and not what it presents itself as and there is a reason why Jefford is loath to admit it.

We would like to believe that the dream of terroir is reality because the idea that a wine is tied to the place it comes from is one of the central tenets of our faith. One that is challenged more and more, in every glass of perfectly made, homogeneous, modern wine. Winemakers and more specifically, wine marketers, like to say, “we grow our wine”. But it is increasingly true that the wine which is ’made’ is the one the world wants to drink.

What did we learn from this exercise? How we go about a deductive tasting has more to do with grape variety and winemaking than with identifying soil characteristics or minerality. Rather than considering minute differences in the soil, which, by and large is pretty much the same, the factor which rules life in Burgundy and especially in the Côte d’Or, is the aspect of the vineyard. In a marginal climate for ripening grapes, how much sunlight you are able to capture depending on which direction your vineyard faces and how sloped it is, is crucial to the final character of the wine.

Whither terroir, then? As this tasting aptly demonstrated, one can still find a glass full of individual personality, reflecting its origins. Yes, there will never be a perfect wine, a wine which is the epitome of its place of birth. But this doesn’t mean that the dream of terroir is not a boon to us. That dream guides us, like a lodestar, deeper into what Aubert de Villaine calls ‘l’aventure des climats’. In the end, there are only people and grapes, there are our mistakes, our happy accidents and skill, and there is Nature’s smiling fortune. Terroir is more than just the earth the vines are planted in or the sun that shines on them. It is also the hand of the winemaker, the hand of the viticulturalist, and, indeed, it is also a dream.

The Wines

Wine #1 – Domaine de Villaine Bouzeron Aligoté 2013 from a top estate. Is this the World’s Best Aligoté? The variety is the key here, aromas of acacia, white flowers, and candied lemon. $37.25 SAQ![]()

Wine #2 – Bailly Lapierre Saint-Bris 2014 Once again given away by the grape variety rather than terroir. Sauvignon Blanc a stone’s throw from Chablis and has more in common with Sancerre and Pouilly-Fumé than it does the rest of Burgundy. $20.30 SAQ![]()

Wine #3 – La Chablisienne Vielles Vignes Chablis 2012 This style of leaner, lighter Chardonnay could be found in Rully, as the Côte Chalonaisse is actually cooler than the Côte d’Or because it doesn’t have the protection of the slope. Often identified through it’s gunflint minerality and lactic notes, this example was immediately recognizable. $24.95 LCBO![]()

Wine #4 – Domaine des Deux Roches Les Terres Noires Saint-Véran 2012 from the heart of southern Mâconnais, one of my favourite appellations for good value Chardonnay from Burgundy. Fleshy and giving “like the hug of an over-sized aunt or uncle” in the words of Szabo, St-Véran is marked by pear and spice for me, round and generous, well-balanced, a little cousin to Meursault. $26.95 LCBO![]()

Wine #5 – Chanson Père & fils Viré-Clessé Bastion de l’Oratoire 2013 from the Mâconnais shows a strong floral note and some phenolic bitterness, “a little more process” says Szabo, “the minerality here is from post-modern winemaking, lots of solids, where wild ferments can give you a sulfitic character, a reductive character that shows as flintiness. I’d be hard-pressed to say exactly what classic Viré-Clessé (the combination of two different villages) is.” $24.25 SAQ![]()

Wine #6 – Louis Jadot Santenay Clos de Malte 2013 in the southern Côte de Beaune, known for its red wines, but this small plot of Chardonnay is right next to some of the greatest white wine appellations in Burgundy. Oaky, delicious, more-ish, looks like the New World, I found the oak too heavy here for the fruit. $42.50 SAQ![]()

Wine #7 – Deux Montille Soeur Frère Rully 2012 Fine oak, elderflower, juicy pear, some spice. Perhaps a little closed at the moment, the quality is there. After seeing wood, the wine goes back into steel and tightens up, the aromatics become purer. $43.00 SAQ![]()

Wine #8 – Domaine Pierre Morey Morey Blanc Auxey[Oh-say]-Duresses 2011 Jackpot. I thought this reminiscent of Puligny, nutty, cheese rind, phenolic bitterness, oxidative. “Perhaps the fruit wasn’t perfect given the vintage”, notes Szabo. Succulent fruit, saline, one of those alluring Burgundians which puzzle you into coming back for more. $54.00 SAQ [sold out]![]()

Wine #9 – Domaine Faiveley Montagny 2011 from the south end of the Côte Chalonaisse, where 1er cru status is perhaps not as rigorous as in the Côte d’Or, this wine lacks a little depth and length while still being in that oaked Chardonnay style, and that combination alone perhaps signals its origins in the Chalonaisse $25.60 SAQ![]()

Wine #10 – Bachey-Legros et Fils Les Grands Charrons Meursault 2011 Meursault is very distinctive and perhaps the most recognizable of all white Burgundies. As the sommelier giving their note described this as “a slutty wine”, or as Szabo noted slyly, “a little bit of a giver”. It is the fat of the wine, the oak and the butter, the flesh of the fruit which gives this wine away. Szabo explains that the slope turns perfectly south-east here and the Comblanchien limestone which dives under the soil in the Côte de Nuits reappears here and shifts the reductive side of the wines, giving you this rancid butter character which is really malo combined with the reductive flinty aspect. $51.95 LCBO![]()

Wine #11 – Domaine Colinot Les Mazelots Irancy 2011 90% Pinot Noir 10% César – here, as with the Aligoté and Sauvignon Blanc, the addition of an off-brand grape variety is the clue. Deeply-coloured, fuller tannins, fresh, floral, unripe fruit, vegetal note, no oak. $28.50 SAQ![]()

Wine #12 – Louis Latour Côte de Nuits-Villages 2012 Ripe red fruits, baking spice, good acidity, a touch of kola nut, good length, well balanced, perfectly representative red Burgundy. The tell here would be the wine’s middle of the road nature. This particular bottling, like much in Burgundy, is very vintage-dependent. $35.00 SAQ![]()

Wine #13 – Savigny-lès-Beaune Vieilles Vignes Seguin-Manuel 2012 This appellation is often described as pretty, fragrant and supple but the winemaking here is angling this wine towards an autumnal and herbal note, a touch of funk and volatile acidity. Sour cherry, forest floor, violet, pepper, and fine tannins. I was perhaps alone in the room in my regard for this wine. $35.25 SAQ![]()

Wine #14 – Domaine Faiveley Mercurey La Framboisière 2013 From the Côte Chalonaisse, lots of acid and tart red fruit and not a lot of oak. A black tea leaf, floral character makes this a little more interesting. “A happy Burgundy”, in Szabo’s words. $33.00 SAQ![]()

Wine #15 – Domaine Chofflet Valdenaire Givry Premier Cru En Choué 2012 Some earthy, mushroom, aromas followed by raspberry, cherry and blackberry, spice on the palate, a little reductive, could be decanted. I often think of Givry in a savoury profile with dried red fruit but the black fruit here put me in mind of the Côte de Nuits. $35.75 SAQ ![]()

Wine #16 – Domaine Olivier Le Temps des C(e)rises Santenay 2012 Noticeably green and stemmy, in fact this has 20% stems included, giving it a grittier texture. Also reductive, this wine would open up with decanting, revealing a deeper character. A more structured example than most red Santenay. $29.15 SAQ![]()

Wine #17 – Lucien Muzard & Fils Maranges 2012 The last village in the Côte d’Or before Bouzeron in the Côte Chalonaisse, black cherry cola, some stem inclusion giving you tannin, paler colour, but also a delicate perfume. $28.30 SAQ![]()

Wine #18 – Domaine René Bouvier Fixin Les Crais De Chêne 2013 Black fruits, black cherry, fine tannins, a more gentile, moreish wine. I was led to Gevrey, the appellation next door, due to the “masculine” and elevated profile. This is a particularly polished example of Fixin. $42.75 SAQ![]()

Wine #19 – Domaine Dujac Morey-Saint-Denis 2013 Top producer. Cinnamon, plush fruit, refined tannin, dark cacao, red cherry, strawberry and raspberry. Great length. Here I was thinking Chambolle, the appellation to the south. In fact, Morey lies between Gevrey and Chambolle and can combine the power of Gevrey and the elegance of Chambolle. $75.50 SAQ![]()

Wine #20 – [not presented] Domaine Rollin Père et Fils Pernand-Vergelesses 2010 Ripe red fruits, baking spice, good acidity and balance, reminiscent of the Latour CdN in its completeness and depth. $32.75 SAQ [sold out, 2011 vintage available]![]()

(All scores are out of a possible five apples)

Christopher Wilton lives in Peterborough and is a wine sales representative for the Small Winemakers Collection, a wine educator at Durham College, a server, and the regional liaison on the CAPS board of directors. He is certified with CMS, is almost finished his WSET Diploma, and has his CSW.

Christopher Wilton lives in Peterborough and is a wine sales representative for the Small Winemakers Collection, a wine educator at Durham College, a server, and the regional liaison on the CAPS board of directors. He is certified with CMS, is almost finished his WSET Diploma, and has his CSW.

An interesting read, however it would seem there is a slight error; the soils of Burgundy…Chardonnay prefers limestone and Pinot Noir more marl content, not the opposite as the article states.