Isabella and the Pot of Basil, by John William Waterhouse 1907

Holy Basil!

On our evening garden walk, we stumble onto an otherworldly scene: a beautiful girl kneeling in the twilight, arms around a pot of basil, abject desolation on her face.

Her name is Isabella, and she is pining for Lorenzo, whose head she has stolen and secreted in some pottery and covered up with a basil plant. Lorenzo, handyman of her dreams, was not rich enough to please her brothers who killed him so that she could not marry him. Her nightly tears make the basil bloom.

The pre-Raphaelite painter John William Waterhouse, was repeatedly drawn to tragic, magic themes that featured melancholy maidens with purple or copper locks and mystical drapery, swirling in waterlilies, vines, or otherwise lush verdure. Like the artists in his circle, he mined poetry and mythology for the most harrowing tales of romantic grief and mysterious transformations. This particular theme was popularized in poetry by John Keats in 1818, fuelling a plethora of basil pot paintings. In turn, Keats reinterpreted the legend from The Decameron, a collection of short stories by Giovanni Boccaccio from the 1300s.

(Read Isabella, or, The Pot of Basil by John Keats 1818 )

It was basil that filled Isabella’s pot because basil was a longstanding symbol of love in Italy. The Italian kitchen could scarcely function without ocimum basilicum, then or now. From everything we know so far, basil has been cultivated in India for at least five thousand years, and likely originated there. But it has been an essential part of Italian culture and cooking for a very long time. From pesto to pasta sauce, Italian cookery is simply impossible without the irresistible tangy aroma of sweet basil. Some sources say the royal herb has been Mediterranean since around 350 BC, coming through Persia, Egypt, and Greece. Others say that sounds about right, but it’s more like 4000 years, having arrived during the ancient spice trade.

Basil in Italy and the world nearby symbolized amore- sweet basil was sometimes called bacianicola or “kiss me, Nicholas.” A pot on a balcony indicated a young woman was open to receiving a suitor. Accepting basil from a woman meant love and marriage were destined. It is still given to loved ones as a potted gift today in Portugal on feast days. But the macabre secret inside Isabella’s basil pot was fitting, too- basil has an ancient tradition and symbolism of mourning. It was used in Egyptian funerary rituals, part of the process of embalming, believed to help the decedents cross over to the next world.

With love and death the parallel symbolic themes behind basil, the story of Isabella’s pot of basil made perfect sense. And it’s operatic tragedy and high romance and mystical underpinnings resonated perfectly with the pre-Raphaelite paintings who lived to paint the terrible, beautiful myths, anywhere love and death could court each other with flowing locks and trembling fingertips.

How does a culinary herb pack so much historical emotional baggage, speaking a symbolic language of both beauty and death?

Humans have always packed meaning into every available space, from random cloud formations and ink blots to colours, flowers, foods, animals, shapes, household objects, patterns, numbers, and assorted sundries. Mundane or routine objects or images become imbued with profound intentions or divine messages. Familiar shapes or botanical sprigs speak a language that reaches into the past and future, across cultures. Choose a motif at random- wheels, crosses, lilacs- and you’ll find a treasury of human creativity imparting profound and dramatic stories to every available concept. Basil is no different. The English used it to ward off unwanted guests, from household callers to fruit flies to evil spirits. Bulgarian, Serbian, and Romanian Orthodox churches use basil to prepare holy water and often place pots of basil below church altars. In ancient China, basil was important as medicine.

Even the name of basil has dual origin stories. Most experts claim the etymology is through Latin “basilius” and Greek “basilikón phutón,” meaning royal or kingly plant. Basil is indeed known by chefs around the world “King of the kitchen,” or the “King of the Herbs.”

But persistent folklore says scorpions and terrible lizards come from basil, and the Greek word “basilisk” refers to a mythic beast of various manifestations. He is “king of the serpents,” a kind of dragon that breathes fire. He is a snake with a chicken head in some imaginings. The basilisk loves death and destruction. His mere touch, indeed, his foul breath, is deadly to receive. Leonardo da Vinci included the basilisk in his Bestiary. “It has on its head a white spot after the fashion of a diadem. It scares all serpents with its whistling. It resembles a snake, but does not move by wriggling but from the centre forwards to the right. It is said that one of these, being killed with a spear by one who was on horse-back, and its venom flowing on the spear, not only the man but the horse also died. It spoils the wheat and not only that which it touches, but where it breathes the grass dries and the stones are split.”

Basil was then sometimes the source of scorpion-like monsters, and sometimes the antidote for stings and snakebites. Greek priests used basil to banish demons. It was so powerful, it was a sign of love and a sign of death.

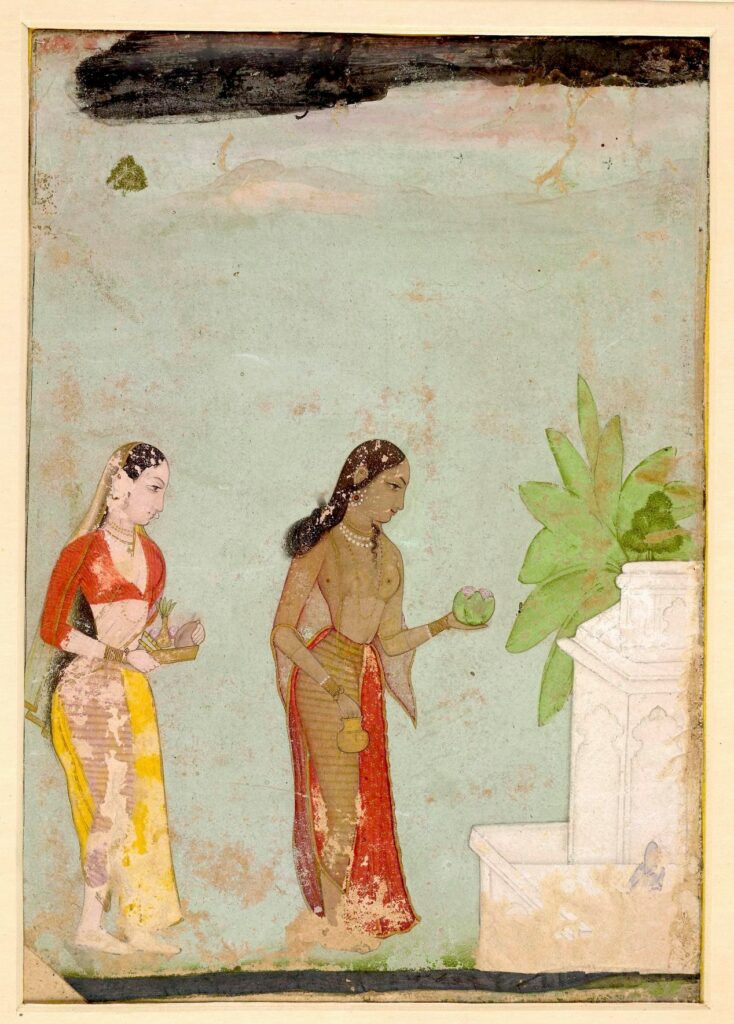

Devotees Worshipping Tulsi Plant, Pahari School Guler Style Punjab Hills c. 1750

The rich folklore and heritage of basil blooms wilder still the further back we go. Today basil has countless cultivars, from sweet basil to lemon basil to Thai basil, and it grows across the globe. But we trace basil to Mother India, where tulsi, or holy basil, is an important sacred plant in the world’s oldest religion, Hinduism.

Holy basil, or O. tenuiflorum, is a cousin to Italy’s O. basilicum, or perhaps great great aunt, depending how you look at it. Vrinda, Tulsi or Tulasi is not just a sacred plant, but the name of the great goddess herself. Tulasi is a representation of Lakshmi, the goddess of fortune, power, beauty and fertility. She is the consort of Lord Vishnu.

Tulsi Devotional Image

Tulsi is known throughout India as “the incomparable one”, “elixir of life” or “queen of the herbs.” Tulsi worship is an ancient and essential practice throughout the history of Hinduism, and though there are many sacred trees and flowers, tulsi is the holiest of all the plants. It is considered a threshold between earth and heaven. Traditional prayers tells us that the creator lives in its branches and all of the deities in its leaves. The Vedas, Hindu’s sacred tests, are understood to flow in the upper branches.

Caring for a basil plant is part of worship, but households with holy basil may also worship with rituals of watering, incense, food offerings, and decoration. Ritual prayer beads can be made out of tulsi wood and worn as a garland. Basil plants keep evil forces at bay.

Holy basil is very rarely used in cuisine. It is consumed as tea instead, as the plant is revered as medicine. Tulsi possesses antioxidant, antiviral, and antimicrobial properties. Basil tea is used for colds, flus, mouth sores, acne, blood sugar balance, and blood purification.

Tulsi Plant and Offerings, India, photo by Haoreima, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Basil’s many varieties have been throughout millennia for medicine. The difficult to describe, astringent, tangy aroma of basil has also been prized in scent-making history. Always royalty, in ancient Arabic perfumery, the basil plant was known as “the kind of the fragrant plants.” It is still used today in contemporary fragrance, including Givenchy’s Xeryus, Mac Jacobs’ Splash of Basil, and Yves Saint Laurent L’Homme. But undeniably, cuisine is basil’s crown jewel. Incidentally, the compounds in basil such as eugenol, linalool, and methyleugenol have also made it useful as a pesticide to keep insects and rodents at bay.

Basil is practically synonymous with Italy, but its complex, bright, and lush flavour profiles are beloved around the world. It is truly a cross-cultural kitchen herb, starring in regional cuisine from tip to toe of one continent after another. Basil must be garden fresh- its leaves are resplendent with various tastes, but its dried version tastes like nothing. The volatile oils

Caprese Salad, photo by Longhorn Nation via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In Italy, pesto depends on basil. And the best bruschetta is heaped in the stuff. Caprese salad- tomato, basil, mozzarella and olive oil- is easy to conjure and heavenly. And the simplest and most profound of all pizzas is the iconic margherita- nothing on it at all except basil.

But Thai cooking also depends on basil. Thai basil, to be precise. Thai basil has notes of anise and luciious lemony, peppery flavours. Green curry needs the herb’s earthy balance. Basil fried rice is absolutely succulent. Perhaps the most famous dish of all is Basil Chicken, or pad kra pao gai. It’s one of the most popular dishes at any Thai restaurant.

Heading towards Vietnam, pho lovers know that half the joy is the fistful of basil sprigs that comes as a side to your soup.

In Nigeria and other parts of west Africa, basil or nchanwu is colloquially known as “scent leaf.” It is invaluable medicinally, for headaches, stomach pains, and skin boils. It is an essential ingredient in pepper soups, chicken dishes, and peanut recipes.

In Brazil and Portugal, leeks with wild basil are a simple and popular side dish.

And lest you think basil is not for dessert, lemon basil shortbread cookies are a serious thing- as is basil gelato and ice cream.

Most of us instinctively grab for fresh leaf bunches of basil when we see them at a market, or reach for a pot of basil at the checkout and tend to it in our kitchen window, pulling off choice leaves and tossing them into a simmering soup. Sometimes we place the pot on our balcony or in our courtyard garden. Without realizing it, we are participating in millennia old spiritual, medical, and culinary rituals, connecting to the wisdom and wonder of our past and future through the spell of basil’s aromatic leaves.

Margherita Pizza, photo by Missvain, CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons