Wine writing in the age of COVID has got weird. At least it has for me. My calendar used to be full of tastings and meetings with producers, and a few press trips every year to see wine being made in its place. Most of the time, I went to the wine. Now, all the time, the wine comes to me. There are some material advantages to this new normal, namely I get more than a pour and keep the bottle for dinner. There are also some disadvantages, like having to explain to your wife, whose working from her desk across the study, that the six open bottles of Chianti Classico on your desk, arrayed around your laptop, constitute ‘work’.

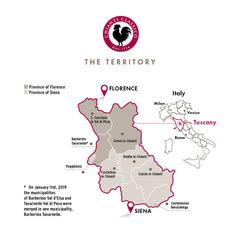

Anyway, I did get some work done this week and got to taste six Chianti Classico wines at a virtual seminar arranged for about a dozen Canadian journalists. The virtual tasting was put together for the consortium of Chianti Classico and featured its president, Giovanni Manetti of Fontodi, who Zoomed in from Tuscany. From Vancouver, the webinar was hosted by the journalist Michaela Morris and organized by Predhomme Inc., who have pivoted seemlessly from real to virtual wine events.. We began with the obligatory Chianti Classico 101 which always begins with the distinction between the small territory of the Chianti Classico DOCG, lying between Florence and Sienna and established in 1716 by the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Cosimo III, and the much larger general region of Chianti DOC. The two are not be confused and, as Manetti firmly explained, Chianti Classico is not a sub-zone of Chianti DOC but its own appelation in its own right. Then, we moved on to the breakdown between the three levels of ‘quality’ in the DOCG. First, the ‘regular wine’, Annata. Then, the step up, Riserva. And finally the new super premium classification, Gran Selezione, established in 2014. Finally the refresher course got into the eight villages or sub-regions of Chianti Classico, with an explanation of typical soils, elevations and all the standard wine geek stuff. (Michel Godel gave GFR an excellent summary of all of this stuff in this post from last November.)

The topics of ‘typology’ or the classifications within the DOCG and the designation of the wines by commune would come-up repeatedly throughout the tasting. We proceeded through the wines moving through three Annata’s, one Riserva, and to Gran Selezione’s. At its launch in 2014, the Gran Selezione was met in the wine world with some controversy. It was seen by many as move to create a super premium label to compete with Italy’s ‘Big B’ wines: Barolo, Barbaresco and Brunello. Nothing wrong with that, except in execution the initial wines tended to be hot and heavily oaked, compared to the Riserva’s and regular ones. At the beginning, only 33 wineries elected to make a Gran Selezione wine, but now, as Manetti explained, there are upwards of 150 participating wineries. Still, the Gran Selezione wines, which must be grown on the winery’s estate and have a longer ageing discipline, only account for 5% of the DOCG’s production.

The topics of ‘typology’ or the classifications within the DOCG and the designation of the wines by commune would come-up repeatedly throughout the tasting. We proceeded through the wines moving through three Annata’s, one Riserva, and to Gran Selezione’s. At its launch in 2014, the Gran Selezione was met in the wine world with some controversy. It was seen by many as move to create a super premium label to compete with Italy’s ‘Big B’ wines: Barolo, Barbaresco and Brunello. Nothing wrong with that, except in execution the initial wines tended to be hot and heavily oaked, compared to the Riserva’s and regular ones. At the beginning, only 33 wineries elected to make a Gran Selezione wine, but now, as Manetti explained, there are upwards of 150 participating wineries. Still, the Gran Selezione wines, which must be grown on the winery’s estate and have a longer ageing discipline, only account for 5% of the DOCG’s production.

At the last in person tasting I attended for Chianti Classico, the wines were arranged on tables representing each of the eight communes and their surrounding areas that sub-divide the appellation. They are, in the Province of Florence: Barberino Tavarnelle, Greve in Chianti, and San Casciano in Val di Pesa. In the Province of Sienna: Castellina in Chianti, Castelnuovo Berardenga, Gaiole in Chianti, Poggibonsi, and Radda in Chianti. Manetti explained on Zoom, that it’s his hope that the consortium will formally adopt the villages as official sub-zones, such that producers may use them as designations on the label, as they do in Barolo. He asked us what we thought of this. Reaction was mixed (by which I really mean, mine). There is always an argument that says that adding information to a wine label only serves to confuse most consumers. On the other hand, for those that care about wine or want to know more, more information is always welcome. Naturally, none of the journalists present was actually against the move. I suspect it will go through since it is in keeping with the terroir focus in the wine trade now, like the move in Chianti Classico away from ‘international’ grapes to indigenous ones for blending with Sangivoese. As Manetti told us, ‘Nobody asks me about what happens in my cellar anymore, they want to know about my soils and vineyards.”

At the last in person tasting I attended for Chianti Classico, the wines were arranged on tables representing each of the eight communes and their surrounding areas that sub-divide the appellation. They are, in the Province of Florence: Barberino Tavarnelle, Greve in Chianti, and San Casciano in Val di Pesa. In the Province of Sienna: Castellina in Chianti, Castelnuovo Berardenga, Gaiole in Chianti, Poggibonsi, and Radda in Chianti. Manetti explained on Zoom, that it’s his hope that the consortium will formally adopt the villages as official sub-zones, such that producers may use them as designations on the label, as they do in Barolo. He asked us what we thought of this. Reaction was mixed (by which I really mean, mine). There is always an argument that says that adding information to a wine label only serves to confuse most consumers. On the other hand, for those that care about wine or want to know more, more information is always welcome. Naturally, none of the journalists present was actually against the move. I suspect it will go through since it is in keeping with the terroir focus in the wine trade now, like the move in Chianti Classico away from ‘international’ grapes to indigenous ones for blending with Sangivoese. As Manetti told us, ‘Nobody asks me about what happens in my cellar anymore, they want to know about my soils and vineyards.”

What we tasted…

The first wine we tasted was the Monteraponi Chianti Classico DOCG 2018, available in Ontario by the case through the Cavinona agency or, in Toronto, the Terroni bottle shops for about $45 a bottle. Made with grapes grown organically on highlands vineyards in Radda, it’s blend of 95% Sangiovese and 5% Caniaolo. It was lovely and ready to drink with clean and clear red cherry fruit, bright acidity and a slightly perfumed bouquet. The first of the three Annata wines, Manetti said he thought the 2018 vintage, which was neither particularly hot nor cool was a good one to compare sub-zones, since much of the taste profile of the wines would come from the micro-climate of a particular vineyard.

Next was the Castello di Bossi Berardenga Chianti Classico DOCG 2016 from the commune of Castelnuovo Berardenga. This struck me as a great contrast to the Monteraponi. It showed spicy, black fruit notes and a vinous earthiness. It’s available at the LCBO Vintages for $22.95, and is a lot of wine for under $25. And the third Annata wine we tried was the Villa Trasqua Chianti Classico DOCG 2016 from Castellina in Chianti. It’s also in Vintages at a very reasonable $18.95. The Villa Trasqua is 80% Sangiovese (the allowed minimum) and 10% Merlot and 10% Cabernet Sauvignon. It’s a complex wine that goes from dark cherry to black fruits and hold up with a firm tannic structure that wants a grilled steak. Manetti told us that many producers are ripping out their Bordeaux grape varieties to grow indigenous ones. Fair enough, but I hope some of the old vines international varieties survive. Now that they are 50 years old or so, some are making great fruit.

It was time to move onto the levels of wines that must be aged longer. Interestingly the Chianti Classico displine does require the wines to be aged in barrel per se, though they almost always are, with the age of the wood and the size of the vessel being the variables. We moved on to the afternoon’s only Riserva, the Tenuta di Nozzole La Forra Chianti Classico Riserva DOCG 2015 from Greve in Chianti. It’s available through The Case For Wine agency for $29.95. A herbal bouquet gives in to deep dark cherry on the palate and finishes with light seasoning of oak. I don’t know, but I bet when this wine was ordered it was meant as a restaurant wine. It would be kind of perfect that way. It punches well above it $30 price tag, so a restaurateur could credibly stretch their mark-up, and it’s in that sweet spot where it could be drunk know or put down for a few years. In this COVID age of eating in this wine might be similarly good consumer investment. I can imagine buying a case now, trying it right away, and then steadily pulling bottles out of the cellar over a few years.

We finished the tasting with two Gran Selezione wines. First, the Castello di Ama San Lorenzo Chianti Classico Gran Selezione DOCG 2015 from Gaiole in Chianti. It’s $56.95 a bottle through Halpern Enterprises. It was lovely with herbal and red and black currant notes and something like liquorice on the finish. The blend is 80% Sangiovese and 13% Merlot and 7% Malvasia Nera. And to finish we poured the certified organic Poggio al Sole Casasilia Chianti Classico Gran Selezione 2015 from Greve in Chianti. It’s available through Heritage Cellars for $59 a bottle. Rich and round dark cherry to black fruit notes held up by a good firm tannic structure, but not so firm and can’t be enjoyed now. And then, it was time to thank our hosts, say goodbye to colleagues on the screen and dream about when we might taste again in person.