This article is part one of a three-part feature on old bush vine Chenin Blanc from South Africa.

The original intent was to write a standalone piece on South African Chenin Blanc but as the words unravelled, I realised that the story could not be told without the sum of its parts, the history that makes enjoying a glass of old bush vine Chenin Blanc from South Africa a remarkable and complex journey.

The History of Wine in South Africa

South Africa, as a wine region, is considered ‘new world’ and credited as a wine region of note post-apartheid. However, I see South Africa as a new world wine region with old world sensibilities. Let’s pause and reread the last two lines. There is much to unpack here, and I will attempt to do so as we continue this series.

The Idea

I attended a tasting showcasing Chenin Blanc and Pinotage of South Africa a few months ago. The Chenin’s were presented by Andrea Mullineux of Mullineux Wines in the Swartland region.

We tasted through eight Chenins, carefully selected to show not only the varied wine styles, of course, because it’s Chenin Blanc, but also the diversity of old bush vine Chenin, depending on its terroir.

That evening at home, I sat eagerly to review my notes from the day’s tasting. Reading, as best I could, my doctor’s style handwriting, I started to realise that I had taken a page and a half worth of notes before we began to taste the wines. As I read through what was on paper, it was clear that I was so consumed by Andrea’s personal story, and her love of old bush vine Chenin that I focused on that… writing down her words that painted a picture of her affinity.

“I really fell in love with Chenin Blanc and old vine Chenin. That was what made me stay in South Africa”. Andrea continued about the wonders and impact of old bush vine Chenin, from the vines’ resilience to the vibrancy in the glass. At that very moment, I knew I had to capture this energy, this feeling, in an article entitled ‘The Old Vines Made Me Do It’.

So, where does one start? How can the story of old bush vine Chenin Blanc be told? You line up very brilliant and passionate wine folk and talk ‘South African Chenin’, that’s how. Discussions with Dr. Edo Heynes of AdVini, Louw Strydom from Ken Forrester Wines, Nicholas Pearce of Nicholas Pearce Wines, and André Morgenthal from the Old Vine Project play a key role in building the final part of this three-part series. What’s more, my discussions with them led me down a path of discovery that was fuelled by a desire to work backward. I wanted to look at key moments in the region’s wine industry that led us to today, where we can now sit in abate, speaking affectionately about South African old bush vine Chenin Blanc.

History

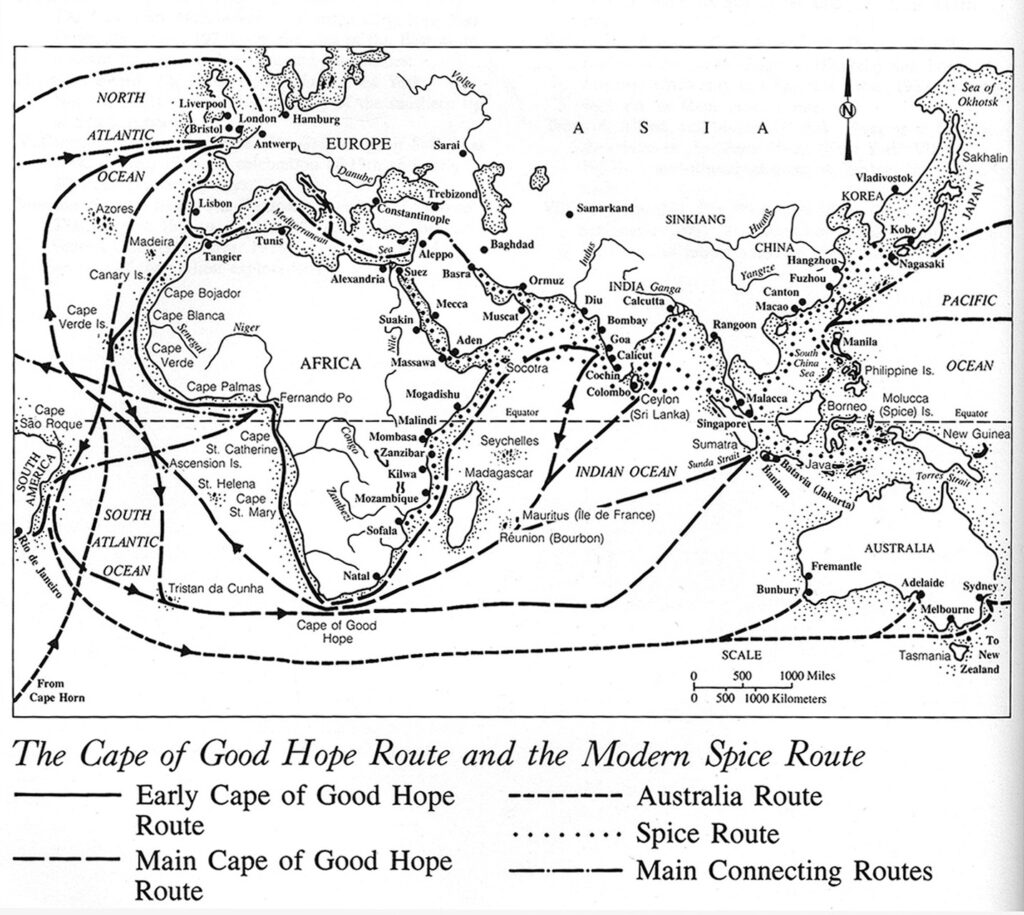

Our story starts in 1652 when the Dutch East India Company installed a settlement in the Cape of Good Hope, as South Africa was known then. The settlement was to act as a refuelling town for merchants and sailors travelling the route from Europe to the East Indies for ‘trade’. Like most historical voyages of a significant length of time, disease was always a concern for fear it could lessen the workforce of seamen or, worse, military numbers. For this reason, the Dutch demanded that wine be made in the Cape to outfit crews who stopped there along the way. The wine was to aid in the prevention of scurvy.

Chenin Blanc is said to be among the first vine cuttings brought to South Africa in 1655 by the Dutch, who eventually produced their first bottle of wine in 1659. The wine was not good by any means but served its medicinal purpose.

Wine really started to take a turn for the better in the Cape with the appointment of Simon Van der Stel as commander in 1679 and then governor in 1691.

Some of you may be familiar with the Van der Stel name as Simon Van der Stel is considered the father of South African wine. If that does not ring a bell, maybe this will; the town of ‘Stellenbosch’ is named after him, ‘stel’s bush’. Of course, we cannot talk about Simon Van der Stel without stating today he would have been considered ‘coloured’ given his pigment and Malaysian background. How is that for irony? The father of South African wine was a person of colour. Nonetheless, Van der Stel recognized the viability of agriculture in Stellenbosch and proceeded to purchase land, with much of it being assigned to grape growing. It is Van der Stel that we have to thank for the early Constantia Wines. These were wines from his Stellenbosch vineyards and a welcomed example of the greatness the area could produce in a bottle.

“With the exception of the Constantia wine, not much good can be said about the quality of the wines produced at the Cape Colony under Dutch rule. The technology and hygiene used in wine-making were less advanced than in regions such as Bordeaux, which produced the highest quality wine at the time”~ Stefan K. Estreicher, A Brief History of Wine in South Africa (source)

The 18th Century Constantia wines were a big deal. The way the world talks about La Romanée is how the wine-drinking world talked about Constantia. Hugh Johnson fashions Constantia as the first wine to come to international acclaim, even before wines from the French regions of Bordeaux and Burgundy. That first vintage of Constantia wine was a white blend that included our beloved Chenin Blanc. In fact, in the 17th and 18th centuries, South Africa was growing Chenin Blanc (Steen), Muscadel, and Pontac in abundance, and all had a role to play in building South Africa’s first wine darling, Constantia.

Deeper into the 18th century, grapes were used to make wines and brandy for export to Europe. South Africa, now known as a budding area for great wines, became a bit of a back pocket supplier as tensions grew and then softened, and then grew again between Britain and France. You see, Britain needed a secure source of wines, and it greatly helped when South Africa came under British rule in 1795. Affordable access to wine was guaranteed, and the Cape benefited from very attractive tariffs, further limiting any buyer’s hesitance toward their wines.

Fast forward to the 19th century, and like many, South Africa’s vines fell victim to Phylloxera. The nasty pest led to farmers ripping out vines and planting other crops such as apples, pears, and lucerne (alfalfa) to ensure revenues. If a farmer chose to stay in wine, they replanted using high-yielding vines to guarantee money through volume. Unfortunately, this all meant less and less Chenin Blanc but more Hermitage (Cinsault), for example.

At this point, the South African darling Constantia Wines was in disarray after being dismantled. Its dissolution was a shame considering that at the time of Phylloxera, Constantia was being used as a collegiate of sorts, in addition to making wine. It was positioned to help elevate and maintain a barometer of quality in South African winemaking. Phylloxera, it seemed, had a different idea.

With high-yielding varieties in lesser regulated environments comes the issue of overproduction and a state of supply that far surpasses the demand, and this was the case in South Africa. It also didn’t help that relations improved between the British and the French, and trade between the two grew. Cape wines were in less of a demand in Europe. Wine was so abundant that some producers started throwing excess wine into rivers and lakes, causing a [literal] wine lake effect.

The wine agri-sector was in trouble. Not only did oversupply mean wastage, but it also meant that grape prices rapidly declined. Given the state of affairs, the government stepped in to regulate production and, in 1918, created the KWV. (The KWV, as you will see in part two of this series, plays a vital role in the story of old vine Chenin or old vines period in South Africa.)

The KWV (Co-operative Winemakers Union of South Africa, translated from Afrikaans) was born from a government’s need to right-size the wine industry and bring it back into financial viability.

Some that I speak to in South African wine today state that the KWV was put in place to support the farmers of the early 20th century. However, the challenges lay in creating a government backed institution that in itself had very little oversight. Yes, the KWV was formed as a cooperative for grape farmers, and yes, it quickly put parameters in place to slow overproduction, but as it gained more power, with no oversight, problems arose.

Amongst other ‘should be’ checkpoints for a government backed agency, is the oversight in the area we refer to today as Social Sustainability.

Applying Social Sustainability to early 20th century industry may seem naive to you; call it what you may. The essence of Social Sustainability calls for leaders (political, industrial, managers, community, etc…) to identify and manage business impacts on every persons involved in the working and makeup of the organisation, and not addressing this is a recipe for disaster that sets an industry up for unavoidable turmoil. The impact of the KWV on farm workers, overall farm worker treatment, and innovation up until the end of the Botha era, in my opinion, was the beginning of the end.

Stay tuned for part two of this series which takes a deeper look at the KWV and its impact on the people of South Africa and wine, including old vine status.

WOSA (Wines Of South Africa) are a Good Food Fighter.

Please support the businesses and organizations that support Good Food Revolution.