Colourful Heirloom Potatoes by Chiot’s Run via Flickr 2010 CC BY 2.0 Deed

You Say Potato, I Say Potato…

The Angelus. It’s one of those paintings embedded in a layer of sediment in our subconscious minds, a little dustier than Starry Night or the water lily ponds.

A farmer stands beside his pitchfork, hat in hands, head bowed. His wife’s hands are clasped under her chin. Dusk is falling over the fields as the peasants give humble thanks in a Prayer for the Potato Crop, the original title. The horizon is broken gently by a faraway steeple.

The Angelus (Prayer for the Potato Crop), by Jean Francois Millet (France) c. 1858

We had a cheap print of this late 1850s work by Jean-Francois Millet in our family room, complete with a perpetually peeling Woolworth’s decal no one bothered to remove. But the painting fascinated me. I was quite sure it was more disturbing than its surface impression.

The magnitude of the theme of man’s survival at the whim of the elements was lost on my youth, even if it was poignant and painful to my peasant-immigrant grandparents and mother. I was looking for something even more romantic than the perils of starvation, since I’d never lacked for a creature comfort or broke my hands open in the soil.

I imagined the mystery in the artwork was a stillborn baby or a buried infant. Perhaps the depiction was not humility in thanks for a few bumpy spuds, but mourning for an undone child. In any event, I was certain the picture was haunted.

All paintings are. They carry the past into the present, take us through a thin veil of pigment and linseed oils back into history. They drag us from one world to another. The mystery deepens the closer you look. Art appreciation is you, as Nancy Drew, trowel in hand at a castle wall. We dig for clues, yield multitudes.

Archeological Reminiscence of Millet’s Angelus, by Salvador Dali (Spain) 1934

I was not the only one digging in the dirt of this small field. The Spanish surrealist Salvador Dali was obsessed by this image, as convinced as I was that there was more buried there than rotten potatoes.

He spent quite a bit of the ‘30s painting numerous surreal spinoffs of Millet’s picture. He was still thinking about it in 1978 when he wrote The Myth of the Tragic Angelus.

At Dali’s behest, the Louvre had the work x-rayed. They found an underpainting of a box they concluded was a child’s coffin. The secret was out.

It’s a story tinged with mystery and the macabre, so of course it appealed greatly to the dramatic likes of Dali and myself. But really, it was hardly a revelation at all. It was exceedingly common with the price of supplies for artists to paint over some narrative and aesthetic choices rather than starting over. It still is. And in this case, the prayer of thanks for the potato crop was really one and the same subject with grief over a deceased child. Countless impoverished rural people died at the mercy of the harvest every year. A million had, in fact, a few years before this was painted. The potato was both symbol and reality of survival for many.

The Potato Harvest, by Jean Francois Millet (Frane) 1855

There was actually a proliferation of potato paintings among the new batch of social realist painters around the time of The Angelus. Millet himself had quite a few others before and after this one. Van Gogh was as smitten by Millet as Dali was, because his tender heart was moved by the plight of miners, farmers, widows, and prostitutes. He painted The Angelus himself and other original pictures featuring farming and eating potatoes.

Besket of Potatoes, by Vincent van Gogh (Netherlands) 1885

Until this time, most of art history was concerned with loftier subject matter, whether historical battle scenes or Biblical or classical mythology. Poor farmers were of zero concern to the traditional patrons of painting. But after the French Revolution, artists became interested in real life on the ground. The 1840s was the time of the Irish Potato Famine, when a million Irish poor starved to death and millions more fled hunger by setting sail to America and migrating wherever else they could. Tens of thousands of other Europeans also starved because of a potato crop blight that robbed the poor of their most important crop. While there were many motivations and reasons behind the various revolutions that swept across Europe in 1948, this famine was one of the dominos.

Gorta-Burying the Child, by Lilian Davidson (Ireland) 1946

The implications and the consequences of the Great Famine were so monumental that we have ever after associated the potato with Ireland. Indeed, the “standard” white potato, the one that we think of when we say “potato” is often called the Irish Potato. But the Irish potato isn’t Irish at all. The Idaho potato isn’t Idahoan. And the Prince Edward Island potato isn’t Canadian. Potatoes, all 4000+ varieties, are native to Peru and the Andes. They have been cultivated for ten thousand years. The Spanish took potatoes back with them after the conquest.

It took a couple of centuries for potatoes to catch on, but when they did, the tasty and nutritious tubers contributed to a population explosion throughout Europe. Peasants quickly learned that combining potatoes with cream and butter provided an abundance of nourishing fuel for new families.

Potatoes by Steven Brown via Flickr 2011 CC BY 2.0 Deed

Potatoes caught on all over the world, and have become one of the largest and most important agricultural productions. They are also massively widespread as fast food and as snacks- the French Fry and the potato chip are possibly the most popular, beloved junk foods on the planet.

Sadly, at the time in Ireland, the dependence on a single dominant crop had tragic consequences when disease ripped through those fields.

The potato also helped build the ancient empires of South America. The Inca especially valued potato cultivation and the star of the Andean mountain table helped their cities expand massively.

Axomamma Potato Goddess Vessel by the Moche people photo by Samuel Austin, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Curiously, a version of the potato prayer that we saw in The Angelus was important in Inca culture, too. The Inca were so indebted to the potato that they worshipped them and prayed directly to them. The potato goddess was a daughter of Pachamama, often interpreted by westerners as “Earth Mother.” Axomamma, Inca potato queen, was a vital sustainer of life, so prayers of thanks and petition for a robust harvest were common. The Inca also buried their dead with potatoes, likely to nourish them on their journey or in the next world.

A farmer holds one of his favourite potato varieties- Photo by H.Holmes:RTB via Flickr CC BY 2.0 Deed

The potato art of the Moche people predates the socially conscious French and Belgian realists by at least a thousand years. The Moche lived on the Andean cordillera in Peru. A great deal of their pottery has been stolen from old graves by looters and some has been found by archeologists. There are a few interesting things about these ceramic vessels: one is that many of them were portrait vessels, believed to represent specific people rather than just generic figures or deities. Another is that they were often comically sexual, with exaggerated positions and endowments. The third is that the potato was a very popular subject.

Peru Farmers sharing potatoes photo by International Institute for Environment and Development 2010 via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0 Deed

While the Andean potato varieties include many white fleshed kinds, there are literally thousands of other sorts. Even in today’s markets in Peru, every basket of potatoes will be a different variety. Many would be unrecognizable to most of us. Some look more like pinecones or rocks. Some are curly and some are very knobby. Some are skinny and some are bulbous. We are familiar with the orange sweet potato, but there are red, purple, brown, yellow, and blue potatoes.

One of my past culinary adventures involved blue potatoes purchased from St. Lawrence market. Living in Toronto means access to global cuisine communities and I’ve always enjoyed exploring the world and experimenting in the kitchen. I invented a cosmic concoction of mashed potatoes that I call Blue and Blue. Using blue Peru potatoes instead of Irish spuds, and melting some funk into the butter with a pungent blue cheese, this smashing feast of gooey starch is food of the gods. However, I once cooked it for a guest who begged to differ. She was convinced the potatoes were moldy and did not believe me that smoky blue tinge of the mash was the flesh of the varietal.

Potatoes by Conall 2022 via Flickr CC BY 2.0 Deed

The blue potatoes are gorgeous and delicious. Many kinds are a bright reds and purples, intense as beets. Any varieties can work nicely for mashed potatoes- those with waxier or starchier textures simply create variety of mouthfeels in the mash. You may be surprised to learn that mashed potatoes are also an ancient invention of Andean cultures, who freeze-dried their spuds, then crushed them into powder that could be preserved and later mixed with milk or fat.

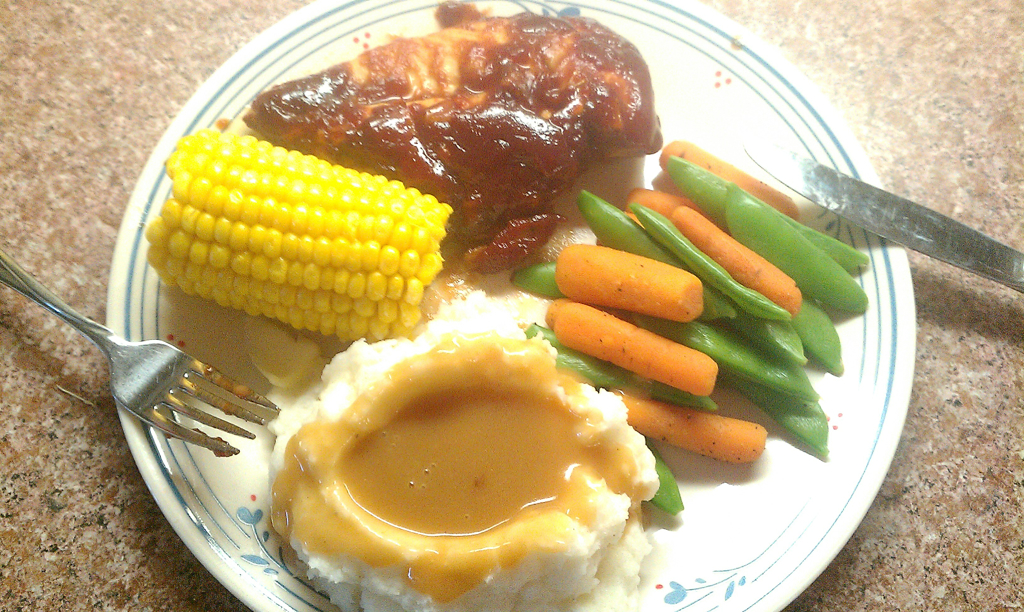

Classic Mashed Potatoes and Gravy, by Midget Skeeter, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Mashed potatoes are one of the most popular dishes at the holiday table, perceived as a kind of decadent comfort food. The butter and cream feel ultra rich, and then oh, glorious, the holiday turkey gravy! Such a dreamy potato pudding seems gluttonous to both low carb and low fat thinkers, but it is exactly the combination that helped people thrive from Poland to Peru.

Potatoes are high in carbohydrates, but at around 20 to 25 grams each, you can still fit a few into a low carb day. Potatoes are naturally fat-free, but fat-free is an outdated way of thinking. Adding butter or cream to the potato dish- soup or mash- gives necessary fatty acids, Vitamin K, D, and A. Your average baked potato contains a nice wallop of Vitamin C and potassium and a wide range of small doses of everything else, including protein. Yes, multiple heaping plates of mashed potatoes daily will make you fat. But enjoy your holiday scoops without anxiety.

You won’t be alone. At Hanukkah time, Jewish people traditionally blended buckwheat, rye, or root veggies like turnips with oil to make latkes. Since the proliferation of potatoes in eastern Europe the past few hundred years, “latke” is practically synonymous with potatoes.

Llapingachos by DFRod via Flickr CC BY 2.0 Deed

Another kind of potato pancake is native to Ecuador, called llapingachos. These are round mashed potato and cheese pucks often dipped in peanut sauce and served with chorizo sausage.

Ireland of course loves the Irish potato, and it is served frequently as champ, or mashed potatoes with scallions, or colcannon, mashed potatoes with cabbage. They also love shepherds’ pie, invented there or nearby in the 1700s from piling leftovers like mashed potatoes, peas, and bits of meat onto a pie plate.

Here in Canada, our national dish is poutine, also called heaven in a heart attack. It’s French fries with melted cheese and gravy.

Poutine, by Shelby L. Bell via Flickr CC BY 2.0 Deed

Papa a la Huancaína is just one of the many Peruvian dishes where spuds take a starring role. It’s simply boiled potatoes in a spicy cheese sauce. Papas Asadas Peruanas, or roasted potatoes, are served with nearly everything. Cause a la limena is a beautiful affair styled like a cake: lemony mashed potatoes layered with avocado and other yummy delights.

Causa a la limena, by F. Delventhal 2019 via Flickr CC BY 2.0 Deed

Patatas bravas are ubiquitous at any tapas table in Spain. They’re just crispy fried potatoes with spicy red sauce drizzled across or tossed throughout.

Potato skins (or potato jackets) are a wildly popular North American dish in casual dining restaurants. They are basically halved potatoes piles high with spices, peppers, cheese, beans, and any other leftovers.

Ajiaco is a simple and stunning soup popular in Colombia.

The French dreamed up potato leek soup, easy to make and prized the world over. They’re also behind aligot, which is basically mashed potatoes, garlic, and melted cheese.

Gnocchi is Italy’s famed potato pasta, delightfully chewy little mouthfuls of yum.

Anytime you see the word “aloo” on an Indian menu, it’s a potato dish! It’s ubiquitous- aloo tikki, aloo posto, aloo pie…

Dumplings from Chile to China to Germany are prepared with potatoes. A very famous kind of dumpling is pierogies, a Polish food beloved around the world.

Potato Monument, Poland, artist Wiesław Adamski JDavid, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Of course, there’s also vodka. It is a commonly held belief that vodka is made with potatoes. Most vodka is made from wheat or rye, but around 3% of today’s vodka makers use potatoes for starch to ferment. You can seek out these brands and may find the vodka is quite flavourful and has a creamier mouthfeel.

Perhaps the humble spud shines brightest in simplicity. The classic baked potato, made at home in the oven or wrapped in tin-foil on a grill or over the campfire flames, is a perfect accompaniment for any menu. Deep frying peeled potatoes adds harrowing contaminants and removes essential nutrition. The baked method keeps the skin in tact and also avoids the dissipation of nutrients into water. All it needs is a generous dollop of grass-fed butter with salt and pepper, but other popular toppings include sour cream and chives, jalepenos, bacon and cheese, and more. The possibilities are endless.

Potatoes- they are the emblem of sustenance and survival, essential peasant food that still tops the comfort food preferences of royalty and Hollywood celebrities alike. Who can resist the most delicious and versatile of all foodstuffs?

In closing, let us turn to a morsel of inspiring verse by one Lillian E. Curtis, from her timeless poem, “The Potato.” This delicious 1872 treasure is an ode to that most humble and useful of provisions, found in the cellar inside the classic Very Bad Poetry, “a compendium of the worst verse ever written in English.”

What on this wide earth,

That is made, or does by nature grow,

Is more homely, yet more beautiful,

Than the useful Potato?

What would this world full of people do,

Rich and poor, high and low,

Were it not for this little-thought-of

But very necessary Potato?

Lorette C. Luzajic

The Three Sisters, by Leon Frederic (Belgium) 1896