Octopus sun-drying out of restauant “Mama Thira”, in Firostefani of Santorini…Klearchos Kapoutsis via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Alien on My Plate: Octopus for Supper

What has three hearts, eight limbs, nine brains, is over 300 million years old, and tastes great hot or cold with lemon and garlic?

You guessed it, the mighty octopus, lord of the sea!

The octopus is a cephalopod, an ancient marine animal with ancestors much older than dinosaurs. This strange creature has a bulbous head and arms and legs we call tentacles that are covered in suction cups. Though it cannot see colour, its body can change instantly to blend in with its surroundings, mimicking textures as well.

The 300 or so species range in size from keychain ornaments to 100 pound giants with 30 feet arm span. Large or small, octopi are shapeshifters who can curl, flatten, crawl, and torpedo themselves through the depths or into small crevices. Their curious composition, ancient presence, supreme intelligence, and mysterious transformational abilities have given them an epic place in history and mythology. They are old gods, longstanding symbols of metamorphosis, and valued worldwide for providing delicious and profoundly nourishing sustenance.

Historically and today, the octopus has been an important animal in Japanese culture and cuisine. The waters around Japan, including the Sea of Japan and the Pacific Ocean, are a favourite habitat of this incredible mollusk.

Hunting the GIant Octopus, by Utagawa Hiroshige lll (Japan) 1877

Many classic works of Japanese art feature fisherman struggling against a massive octopus. A familiar work is by a student of Utagawa Hiroshige, depicting fishermen in a fragile boat, their small knives and vessel absolutely dwarfed by a Pacific Giant of exaggerated proportions.

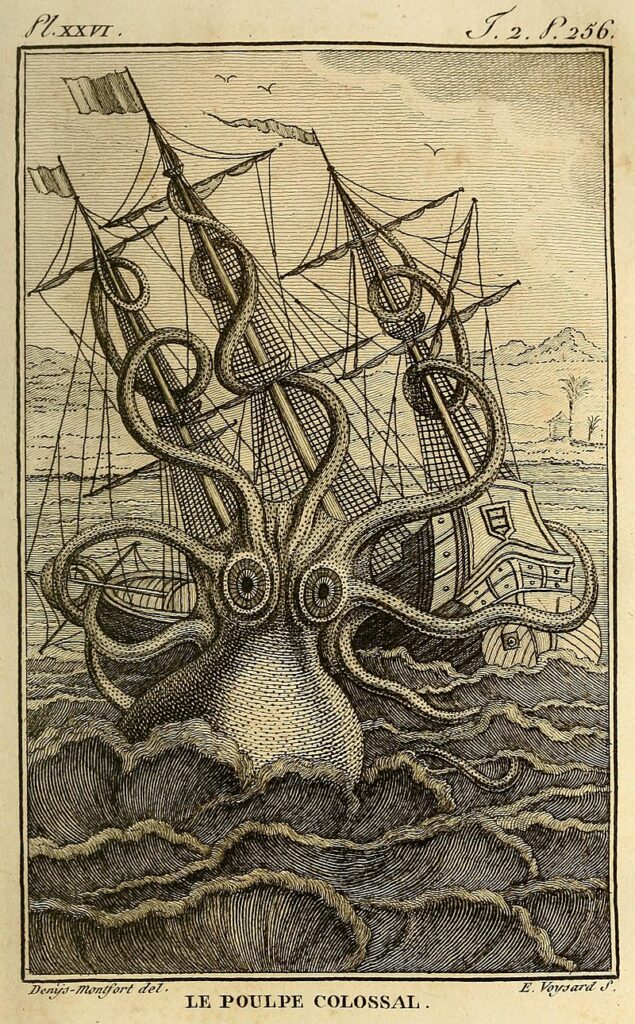

The octopus was frequently portrayed as a terrifying monster because it is a powerful predator. The octopus was seen as great warrior and a symbol of flexibility, adaptability, and transformation. It was a foe naturally endowed with eight tentacles. The Big Red of the Pacific was the stuff of legends, turning up in folklore as Akkorokamui, a sea god believed to inhabit the waters near Hokkaido. In this Shinto belief, the giant octopus could regenerate its body and hence stood for healing and good luck, but you did not want to be on its bad side. Akkorokamui has a Nordic cousin or counterpart in the Kraken, feared by sailors for its ability to effortlessly sink a ship.

Le Poulpe Colossal, by Pierre Dénys (France) 1801

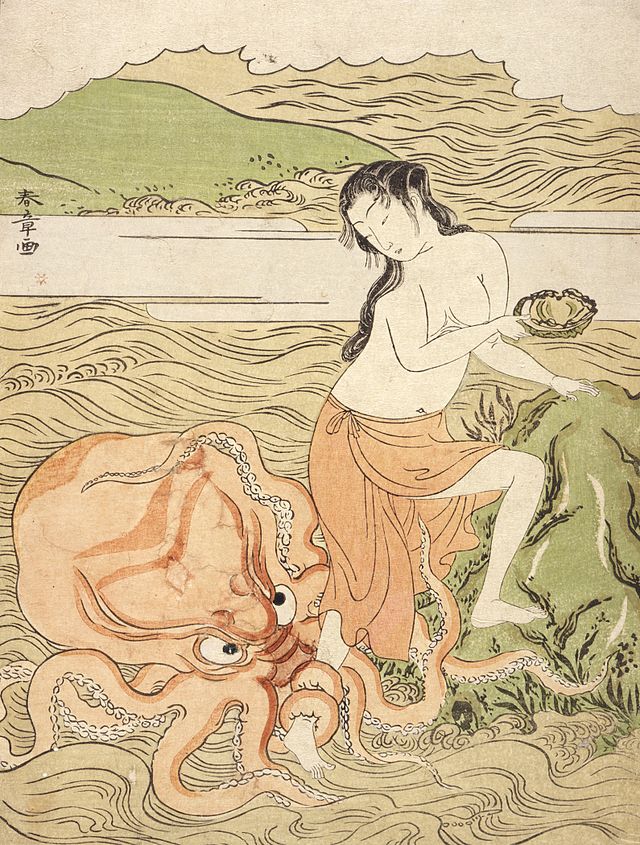

The octopus was also the envy of everyman for its imaginary prowess as a….lover? Antique Japanese erotica occasionally featured the most unusual competitor, with shunga paintings showing ecstatic women entwined with octopi. An infamous 1814 ukiyo-e artwork by none other than Hokusai, world revered artist of the Great Wave and more, shocked western audiences for its frank portrayal of a fisherman’s wife in an unusual threeway with two octopi.

It is probably too racy to post here, but if you are game, can easily be found online. The legendary lover is gustily pleasuring Wifey with his mouth while his mate kisses her, arms everywhere. This was not the first, or the last, such illustration. The fishy dalliance was a recurring motif in literature, noh and kabuki theatre, and art. A fully pornographic rendering by Katsukawa Shunsho dated to 1786, and another, Octopus and Pearl Diver, by Kitao Shigemasa, dated to 1781. A beautiful artwork by Shunsho on the same theme that is work friendly for your browser is shown here to illustrate the genre.

Abalone Fishergirl with Octopus, by Katsukawa Shunsho (Japan) 1773

The secret fantasies of housewives for a beach romance notwithstanding, the Japanese more often have the octopus on the other side of the fork. Seafood, including sushi, is a mainstay of Japanese food, with a wide variety of sea creatures and sea vegetables on the table. Octopus is a longtime favourite. It has a tender and slightly rubbery texture that is very pleasurable to chew, and the flavour is very mild rather than fishy, making it very versatile. Nidako means simmered octopus. Takoyaki is a delicious and popular snack or appetizer, featuring battered balls of chewy octopus, seasoned with savory fats and a wide array of dipping sauces. Also, pickled octopi is a thing.

Controversially, there is delicacy eating octopi odorigui style. This translates to “dancing food,” and refers to the custom of eating fish that are still alive. This is also a tradition in Korea, where it is called sannakji, or “wriggling octopus.”

Sannakji, by Kirk K (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) via Flickr

While the uninitiated may recoil from this style of preparation, and rare today, it is not an uncommon way to consume our food historically. Oysters are alive when served on the half shell with a drop of shallot vinegar and chile. Jumiles are a popular snack in Mexico, a stink bug variety that is preferably eaten alive for its full flavour.

However, odorigui style is falling out of favour as we learn more about how sensitive octopi are to pain. Malacologists and animal advocates have urged us to reconsider this practice. Sannakji is still quite popular in South Korea, but today is mostly served freshly killed. The octopi tentacles are still wiggling around because of their nerve makeup, giving adventurous eaters a squirming experience.

While the suffering of the cephalopod is a good reason to avoid eating her alive, there are other reasons: people have died this way. It is easy to choke or suffocate on the desperate dangling tentacles as the poor creature fights back. The suction cups can latch on to the esophagus. The beast will eventually succumb to your stomach acids, but it can be a narrow escape. Food and Wine Magazine reports that about six people die eating living octopi every year.

If you’re thinking that sannakji is the weirdest octopus recipe going, you are wrong. For that, you need to travel halfway around the world, to Kalymnos, a tiny island in Greece. This destination has a long history of unusual (to us) seafoods. One thing they are known for is octopus ink paste. They also fry and poach breaded octopus ink sacs at local restaurants. Atlas Obscura reports that the dish is like porridge with “the rich gaminess of chicken liver.” There is no official name for this rare delicacy.

Octopuses, by Adam Polselli(CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) via Flickr

Octopus is historically as essential to food and folklore in and around Greece as it is to Japan. This sea animal is a staple on the Mediterranean table to this day, starring frequently in simple grilled recipes and marinated in salads. It’s a familiar sight even in modern villages to view octopi sun drying on lines like the morning’s wash.

Marine Style Minoan flask with octopus, c. 1500-1450 BCE, by Wolfgang Sauber, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The motif of the octopus has long been familiar in the region. Early ceramics were frequently decorated with octopi. Minoan marine-style flasks and vases abound in museums, harking back to 1500 BCE. Octopi figured prominently into fables, myths, and pre-Christian worship, representing the tempestuous and important spirits of the sea. They were frequently used to decorate larnakes, which were small boxes that served as coffins for ashes or bones.

Minoan Larnax 1370 – 1340 BC by Egisto Sani (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) via Flickr

The octopus shows up for dinner throughout the entire Mediterranean, not just the Aegean islands. In Tunisia, octopus makes a beloved kamounia or stew. It’s quite simple to make and worth trying if you enjoy spicy and hearty meals in a bowl.

Octopus stew is very different in the Azores. Polvo guisado a moda dos Azores is cooked with pimenta de terra, a local pepper paste, and a homemade Azorean red wine.

The mainland of Portugal has octopi in some incarnation on most menus, from octopus sandwiches to octopus with rice to octopus salads.

This delicious leggy beast is just as historic on the menus of neighbouring Spain. The Galicia region is especially fond of the stuff and has a long list of recipes passed down through the generations. A famous one is pulpo Gallego, familiar in my most tapas repertoires throughout the country. It is very simple: superbly tender rounds of octopus tentacles seasoned with olive oil, salt, and paprika.

Spain, Octopus Galician Style, by Xosé Castro Roig (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) via Flickr

Octopi options were so common in Spanish households and in small tavernas that the latter were called pulperias. These idyllic and rustic little bistros, basking in the ocean breeze, often sold a small assortment of foodstuffs or sundries as well. Today, small food stores throughout Spanish America are still called pulperias just as often as they are called bodegas.

Here in Canada and our neighbour to the south, America, it’s a little unusual to answer “octopus soup” when the inevitable question comes up, “what’s for dinner?” You can find fresh octopus at specialty or larger markets, and you’ll easily find it on the menus of Greek and Portuguese restaurants or sushi houses. Still, even foodies may not be sure how to cook their own, or what wine should go with it.

Perhaps this is because so much of our large countries are inland, not coastal. Maybe it’s because we forgot how staple seafood should be when food started coming in boxes and tins. Maybe it’s because fish is only fresh briefly and best left to professional hands.

Yours truly with the grilled octopus at Pantheon on the Danforth, Toronto.

But octopus IS a traditional and historic Canadian food and an important motif in folklore, too. It was common to the cuisine of the Indigenous people of the west or Pacific coast, including the Makah, Tlingit, Quileute, Haida, Coast Salish, Nootka, and Kwakwaka’wakw people, among others. Many coastal cultures ate octopi, as well as using their tentacles for fishing bait for other seafood.

The octopus appears in a number of legends, stories, artworks, and other cultural traditions of Haida and other Indigenous peoples. While we often think of animals like thunderbirds, bears, or salmon when we visualize Canadian Indigenous art, the octopus is a recurring motif. As with Asian cultures across the Pacific, and Greek traditions, the octopus, often translated to Devil Fish by the English colonizers, symbolized metamorphosis and power.

The formline works of west coast people are particularly stunning. Click here to view an amazing octopus artwork by Kwakwaka’wakw artist Mark Henderson.

The octopus also appeared with other animals on totem poles. The one shown is a well known totem in Alaska.

Octopus at Totem Bight State Park, by David O (CC BY 2.0) via Flickr

Even with an increasing number of people choosing to try octopus dishes, and the growing popularity of Japanese and Korean foods throughout the world, octopus is still an occasional choice or a culinary adventure for many. It’s one of the remaining foods that a large part of the population has simply not yet tried. Even if we do try it, and like it, we probably don’t incorporate octopus regularly into our menus.

What gives? Octopus is a delicious seafood that is low in calories and high in nutrients. It has a range of important vitamins and minerals, as well as Omega 3 fatty acids which we desperately need more of in our diets. Octopus is very high in B12- one tiny portion is more than 1000 percent of the daily value recommended. The same serving serves up 140% of the selenium you need, a mineral that is not always easy to eat. There’s a third of the B6 you need for the day, almost half the iron, and generous doses of copper, niacin, choline, pantothenic acid, magnesium, and potassium. Without seafood in general we end up substituting foods with much lower nutritional density. Octopus in particular is quite high in a wide variety of good stuff we need.

Barbecued Octopus with Smoked Butternut Squash Puree, Bywater American Bistro, New Orleans, by ChrisGoldNY(CC BY-NC 2.0) via Flickr

Some people don’t care for the rubbery texture, or the texture of the suction sections. Some people grapple with the aesthetics of octopus eating. The tentacles are tricky to tackle. Some of us are ready and willing, but find cooking with all those tentacles intimidating, even if we enjoy eating the final result. Of course vegetarians choose not to eat any animals, but flesh eaters sometimes avoid octopi because they are perceived as more enigmatic and intelligent than other animals, and it may feel wrong to eat them. Still others feel octopus consumption is bad for environment and not ultimately sustainable on a larger scale. Many are worried about the hazards of mercury and other toxins in seafood.

A lot to unpack here. A few of these are simply preferences, but some are thoughtful considerations. It is true that our oceans are full of terrible toxins, but so are our soil and air. Choosing wild foods more often can help, but short of not eating at all, the problem is bigger than what we put on our plate. Without the wallop of nutrients in high quality foods, we can’t hope to manage our health through all these toxins!

While we definitely need to change our practices in fishing and farming all around, octopus eating is far from the worst when it comes to sustainability. Because octopi have a relatively short life span and are constantly renewing cycles, they are actually a decent resource.

Yes, the octopus is highly intelligent and holds intriguing clues to consciousness in general. They recognize people, and other animals. They have personal preferences for friendship and play. They have superpowers like becoming flat or small or elongated, or changing colour and texture. They are so alien to us as mammals that we want to protect them. We find them mysterious and beautiful.

Red Tentacles, by Xynalia (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) Via Flickr

But if you’ve made your peace with the fact that humans are omnivores and predators, the octopus is not really less edible than a cow or chicken. Every animal has its charms and intelligence. Pigs have incredible long-term memory and recognize people- and so do cows. I love all of them, and choose to focus on finding pastured foods and hoping we can change the terrible truth about factory farms. A wild caught octopi suffers much less than a chicken born in a factory.

Just like us, octopi are predatory carnivores. They are voracious eaters and like fish, shrimp, starfish, scallops, and crabs. They are also cannibals. The female sometimes has her mate for supper, after finishing with him in the mermaid boudoir. But it’s not just kinky mating rituals. Octopi eat each other and they eat other octopi species. So what you eschew may be spoils for a sibling or cousin octopus.

As for cooking at home, there are some tricks to tenderizing the tentacles to tame the assaulting textures. Boiling, freezing, and slow cooking are just a few of the ways you can use to make octopus an extremely pleasant meal. I quite enjoy the chewy mouthfeel and find it satisfying. I have a bit more trouble with the texture of the suction cups. The tentacles can be cut into round slices or chunks to minimize how much wiggle and suck are in each mouthful.

Our Good Food editor Jamie Drummond wrestled with making octopus at home and came up with perfection. He shared it right here last year, so perhaps trying his braised octopus is a good place to start!

Whether you love polpo DIY at home, or stick to occasional forays during a sashimi bender, or avoid octopi altogether out of respect or disgust, you might get a little chuckle out of this classic Ogden Nash poem in closing.

Tell me, O Octopus, I begs

Is those things arms, or is they legs?

I marvel at thee, Octopus;

If I were thou, I’d call me Us.

Lorette C. Luzajic

Ivory Octopus Netsuke, 1800s, Japan, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Hanged Sun Dried Octopus in Antiparos, by Raul Villalon via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)