by Kerry Knight

In the movie, “I’m Not Scared” 10-year-old Michele discovers a boy trapped in a hole in the ground and takes it upon himself to feed him. So he goes to the shop in his small village and ponders how to spend his 500 lire. Tempted by an array of chocolate bars and other goodies, he asks the proprietress, Assunta, “What do you give someone who is hungry?”

Assunta responds matter of factly, immediately, without missing a beat, “Bread. When someone is hungry you give them bread.”

Every culture on earth has a type of bread as a staple in its diet. The stuff of legend, metaphors, religious ritual, the staff of life. And every butcher, baker, or candlestick maker at some point or other has had a go at making bread. Most of us had a crazy aunt with a one eyed cat named Mehitabel and a gurgling blob of sourdough starter in a scary stinky bin. Do not put the cat in there, that starter has been around since the Great War. It was not the cat that intrigued us, it was the living, breathing, sinister sponge of sourdough.

Perhaps your first attempts at baking bread were without a recipe, techniques cobbled from observation and intuition, ingredients cheap and plentiful, time on your side. There is a certain magic that occurs, this blending of flour, yeast, water, the marriage of science and, as Paul Allam puts it, “river running romance.” We don’t really know how a TV works, most of us, but we know what we like to watch. And we don’t really know how bread works, how it becomes more than the sum of its parts, but we like to eat it. And if it is not a total disaster, we bring it to a potluck, proudly bragging, “Yes, I made that”

After your first dozen few attempts, maybe a loaf of unassuming, simple white bread or a molasses oatmeal bread made from leftover memories, you are ready to get a little adventurous.

You discover-the first human to do so-that you can put just about anything in the dough, knead it, let it rise, bake it, and this will be your savory baby or your sweet bun bun.

Then you hit a few potholes, a few disasters. You have discovered wormwood is not an acceptable spice with which to flavour your bread. Certain flours will have you shaking a fist at the floor, yelling at the ceiling. It is gummy, it is dry it didn’t rise, it is a brick, the crust is burnt, or the loaf seems like it had been interred with The Boy King and before you know it you resolve never to bake another loaf, divorce is imminent. “Support Your Local Artisan Bakery” becomes your new mantra, you are moving on, your are learning how a TV works.

Certainly there is no shortage of information, this is after all, the information age, right here a your fingertips, all you need to know, a click away. TMI, really, as the chocaholics say. If only there were one book that had it all, a book that explained the science but did not destroy the magic, a book that you felt you could trust, that would only let you down gently if you messed up. A cookbook that you could count on.

I love “Top Ten Lists”, I make them all the time. In my “Top Ten Things About Australia”, the word “Bakery” does not appear. Visions of Elle Macpherson may dance in my head, not sugarplums, or baguettes. You’d have to look down, way down another list, maybe right before Crocodile Dundee and certainly after Evonne Goolagong.

David McGuinness and Paul Allam opened Bourke Street Bakery in 2004, in Surry Hills, Sydney. That doesn’t seem very long ago to me, a scant four years after Simon Whitfield churned the murky Harbour waters and tore it up in the Sydney streets. I wonder if David and Paul were there, watching all these scrawny triathletes whiz by, thinking, “You know, what that guy needs is a good rabbit and quince pie. We must help him out.”

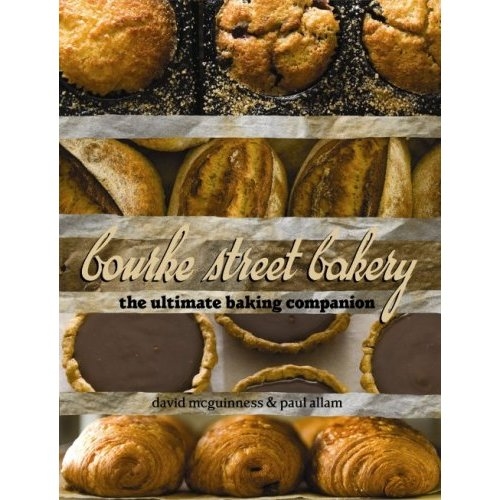

The Bakery was a hit from day one, and has moved and enlarged since then, but maintained its core values; no marketing or PR people were involved. “The growth of Bourke Street Bakery has been totally organic… We took our time. We did it well. We stayed true to our product.” And this year they have produced one of the most beautiful and thorough cookbooks I’ve had the pleasure to drool over.

Even if you have your favorite cookbooks that you are intensely loyal to, if a Danish is Greek to you or you have sworn to never attempt a croissant again, or wrestle with a stubborn and derivative bread, this book will entice and bewitch you with it’s hail-fellow-well-met prose and its stunning photography. There is a double page photo of a pizza (yes, a pizza) that will have you searching for the staple in its belly, you will want this picture in your secret room, festooned with photos of pies, croissants and tarts that will make you blush. Indeed, man does not live on bread alone.

The authors are good story tellers too, and most of the recipes are enriched with accounts of their own experiences with a certain recipe, or a brief history explaining its provenance.

This by way of introducing three pissadelieres; fig, prosciutto and gorgonzola, red capsicum, anchovy, olive and goat’s cheese, mushroom and herb, all on puff pastry.

It is touches like this that make Bourke Street Bakery a pleasure to read, a companion on those days when you can’t tolerate anyone, days when you want to curl up with a good book, even if you have no plans on rolling up your sleeves and throwing another log in the stove.

I haven’t been to Australia, but there are certain sights I will visit when I do go. Bourke Street Bakery is one of them. Until then, I have this book.

Kerry Knight is a starving writer who has been eating all his life. Growing up in a family with eight others, he learned to read devouring the collected works of Kate Aitkin and Mary Moore. He lives in Parkdale and regularly cooks for his wife Ivy and his three dogs, Poppy, Betty and Peabody. Follow Kerry Knight at twitter.com/keppsterr.

Kerry Knight is a starving writer who has been eating all his life. Growing up in a family with eight others, he learned to read devouring the collected works of Kate Aitkin and Mary Moore. He lives in Parkdale and regularly cooks for his wife Ivy and his three dogs, Poppy, Betty and Peabody. Follow Kerry Knight at twitter.com/keppsterr.

Ivy Knight just emailed saying, “The Toronto launch for the book will be held this Monday, Oct.18th at The Drake Hotel and will feature a bake-off pitting 5 Toronto food bloggers against each other to see who can come up with the most perfectly realized recipe from the Bourke St. Bakery’s repertoire. The bloggers behind http://www.canadianfoodiegirl.com, http://www.foodwithlegs.com, http://www.communityfoodist.com, http://www.one-more-bite.com and http://www.kristinagroeger.com are the contestants. Everyone is welcome to come, try out the entries and vote for their favourite. Lots of great prizes to be won, listen to CIUT’s morning show this Monday for more details and an interview with one of the bloggers.”