If my fondest childhood memories are coloured with the vivid flavours of Hyderabadi food, Indian Chinese cuisine inspires in me an equally poignant nostalgia for the halcyon days of my time at university in India. Several times a week, usually on weeknights, my friends and I would walk over to our favourite Chinese street food carts/stalls, colloquially called “thelas”, to pick up some take-out. The food was delicious, of course, but waiting as the thelawala (street food vendor) made our dinner was a unique sensory experience, riveting in its own way. The sleight of hand the vendors displayed was a sight to behold as they skillfully and swiftly stirred, tossed, and combined copious amounts of oil, ginger, garlic, spices, and our choice of protein together in enormous, greasy woks. So evocative were the colours, aromas, and sounds of sizzling, blistering garlic, ginger, and chilli, alongside other spices that I need only close my eyes all these years later to be transported back to the side of a street in Pune, eagerly awaiting my dinner.

A Brief History of Indian Chinese Food

How did Indian Chinese food come to be? The history of Indian Chinese food is a story of trade, migration, and colonization. The most popular and widely accepted account of its origins takes us to Kolkata, the capital of West Bengal in Eastern India. By the late eighteenth century Kolkata, then called Calcutta was already an important port for the British East India Company’s trade with China. In 1772 it became the capital of colonial India. The city therefore began to attract an increasing number of mostly male Chinese immigrants. The first historical record of a Chinese settler in India is that of Tong Atchew who established a sugar mill near the city in the late eighteenth century. Interestingly, one of the words for “sugar” in Hindi is chini, which is also the word for “Chinese”.

The close of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century saw many Chinese people immigrating not only to Kolkata, but also to Bombay on the west coast of India. As the Chinese community in the subcontinent grew, Chinese restaurants began popping up. Gradually, the cuisine adapted to please local palates and morphed into an amalgamation of some of the best aspects of Indian and Chinese food cultures.

Following the India–China conflict of 1962, the Chinese population in South Asia began to decline precipitously. By then, however, Chinese cuisine had already had a profound and enduring impact on the Indian culinary landscape. Today, Indian Chinese food is not only an indelible part of Indian cuisine, but it continues to evolve and interact with other South Asian cuisines. It is increasingly common to see Chilli Idlis and Szechuan Dosas in South Indian restaurants both in India and abroad, for instance.

What is Indian Chinese Food?

How was Indian Chinese food able to capture and hold the Indian imagination so firmly given India’s already rich culinary traditions? One interesting theory that Indian food writer Vir Sanghvi espouses is that other Indian cuisines feature little to no umami in them, whereas Indian Chinese food is infused with it (you can read his essay on this topic here)!

Indian Chinese food brings together two rich culinary traditions in a spectacle of flavour and texture. Today it can be found wherever a South Asian community exists. It is usually made with spices, proteins, and vegetables that are ubiquitous in the subcontinent. That said, a few ingredients often used in Chinese gastronomy and seldom found in other Indian foods, like soy sauce and vinegar, play a vital role in this cuisine.

Hot and Spicy; Sweet-and-sour

When talking about Indian Chinese cuisine in the context of wine, it is useful to think about it in terms of two broad groups of recipes or preparations. The first group is made up of savoury, salty, spicy base-sauces like Manchurian (read more about the history of this sauce here), Szechuan, and Chilli, to which different proteins are added. These proteins include paneer, fish, shrimp, chicken, and vegetable-based dumplings. Some of these preparations have distinct herbaceous and/or herbal flavours, often being made with vegetables as a base and cilantro as a garnish.

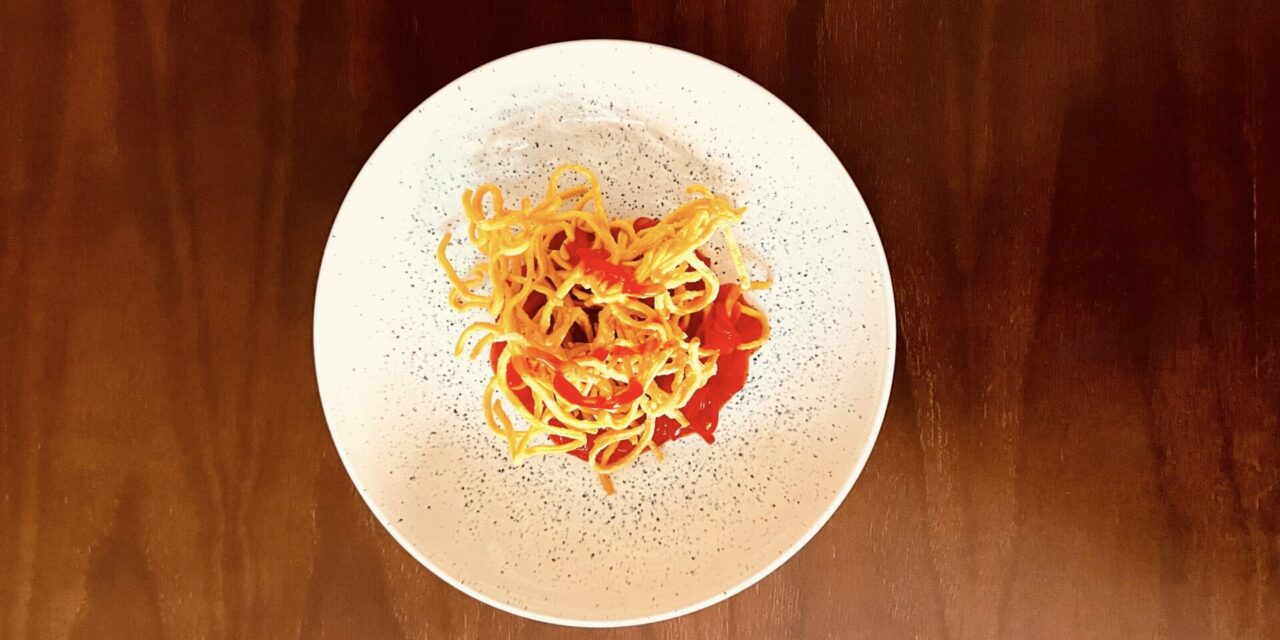

Meanwhile, preparations like Sweet-and-sour Vegetables/Chicken and American Chop Suey (read more about this unique South Asian preparation here) fall into the second category of Indian Chinese food. Although these sauces are also seasoned with spice, they are relatively delicately flavoured and predominantly sweet-and-sour, rather than hot and spicy. Crunchy vegetables, such as beansprouts and cabbage, are added to these preparations contributing not only flavour, but also textural complexity.

Pairing Wine with Indian Chinese Food

The distinction between these two categories of Indian Chinese food is crucial in the context of wine pairing. Many wines that work well with the first group of foods/sauces do not work with the second. The exception to this general rule being an off-dry white wine, brimming with fruit, and underpinned by bright acidity. Off-dry Chenin Blancs, for example, such as those from Vouvray, can complement both types of this cuisine especially well. These wines tend to be honeyed and perceptibly sweet, but vibrant and crisp, and are lush with orchard and citrus fruit flavours. All of this makes them excellent partners to both savoury, spicy examples of Indian Chinese cuisine, and sweet, tangy, more delicately spiced expressions of it.

Hot and Spicy

The most important features of this category of Indian Chinese food are that they are usually spicy, oily, and salty. They are bold, with effusive flavours, including lots of chilli, garlic, ginger, and onions. Finally, and perhaps most distinctively, they contain high levels of umami, unlike other South Asian cuisines.

Like Hyderabadi food, I have found that this category of Indian Chinese food pairs relatively easily with white wine. Bright, crisp whites with an undercurrent of salinity and vibrant citrus fruit flavours seem to serve as a welcome contrast to the structure and flavours of this food. Consider fresh, fruit-forward Italian whites like Pecorino from Marche and Abruzzo or a Sicilian Grillo. Their acidity and tart citrus fruit flavours cut through the grease in the food, while the food highlights the fruit flavours in these wines. In addition, I tried a Vermentino and an Etna Bianco with an assortment of foods in this category and found both pairings refreshing and pleasant. I especially liked how the savoury, mineral, saline character of the Etna Bianco supplemented the food. I also liked the grapefruit-inflected impression both wines left on my palate in between spoonfulls of food. A caveat is that some may find that both these wines finish on a slightly lean and bitter note.

Unsurprisingly, Sauvignon Blanc is also a reliable choice; its acidity is similarly refreshing, while its ripe fruit notes add dimension to the flavour profile of the food. For those who like a bit of sweetness in their wine to balance the heat in spicy cuisine, as noted, Vouvray pairs harmoniously with this type of food. A sparkling rosé with fresh acidity and bit of residual sugar is also a good option. It cleanses the palate with its revitalizing effervescence and lively acidity, while crunchy red fruit flavours and subtle sweetness underscore the savoury, herbal, and spicy notes in the food.

Finally, a youthful, tart gamay, saturated with red fruit, can work well with this category of Indian Chinese cuisine. As in the case of some white wines, however, there is some bitterness and astringency on the finish that might not appeal to some people.

Sweet-and-sour

With respect to the second category of Indian Chinese food, finding wine that does not shrink into something mean and lean when juxtaposed with sweet-and-sour sauces was initially slightly challenging. Every red wine and every dry white wine I tried did not show well when served with this type of food.

As noted, Vouvray, or other similar off-dry white wines with firm acidity, can pair well with it. If you are feeling adventurous though, I recommend trying sweet-and-sour Indian Chinese food with sweet dessert wines. I tasted it with an Austrian icewine made with Grüner Veltliner and a glass of Tokaji Aszù and both combinations were delicious. While the wines’ acidity cleansed and refreshed the palate, the food highlighted dried fruit and honeyed notes in both wines. When juxtaposed with the Tokaji the sweet-and-sour sauce seemed to heighten the wine’s orange marmalade flavours in a pleasing way. I must warn you though, combining sweet-and-sour Indian Chinese food with sweet wine makes for a rich and substantial meal; you will probably want to forego dessert.

A Final Note

If you are interesting in reading more about the history of Indian Chinese food this piece by Maria Thomas and this article by Sanjiv Khamgaonkar are interesting reads. For those who are interested in trying some “authentic” Indian Chinese food, I recommend Royal Chinese Seafood Restaurant in Scarborough. For something a little closer to downtown Toronto, Yueh Tung is worth a visit. Here is hoping you get to try some delicious food and wine this weekend!