Gum Alley, Seattle, by Ken Walton (CC BY 2.0).

Pop Goes the World: the Chewing Gum Story

In 2009, outside and outsider artist Ben Wilson was arrested by the City of London Police on suspicion of criminal damage. The street artist, known for creating art from found wood or recycling refuse into sculpture, was also known as The Chewing Gum Man. He would take throwaway wads of gum- the second most common kind of street litter in the world, after cigarette butts, and paint them right where they were on the sidewalk. He painted storefronts, strawberries, bacon and eggs, taxis, coffee cups, nudes, angels, and colourful patterns onto squashed gum wherever he found it.

Gory gum discards are a massive public nuisance and waste disposal problem worldwide. They are also an environmental disaster. Gum is not biodegradable, and even worse, the solvents and disinfectants used to clean it off the streets, public transit, school desks, and more are toxic. Britain spends 150 million pounds each year removing gum from pavement. Stats for the scope of the problem elsewhere are difficult to find, but Canadian filmmaker Andrew Nisker, director of Dark Side of the Chew, told The Atlantic that Toronto drowns in about 2000 tonnes of gum a year.

Millennium Bridge Chewing Gum Art by Ben Wilson, photo by Loz Pycock (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Ben Wilson felt that using the ubiquitous gum gobs for miniature paintings both beautified the situation and provided an unusual source of canvas. He created his tiny paintings wherever he found the gum. By 2011, The Daily Telegraph reported that he had already made ten thousand miniature gum paintings on the streets. Ben’s fans rallied behind him and wrote letters requesting he be exonerated of the criminal accusations. Ultimately, the charged were dropped. Ben was not, after all, painting and “damaging” the pavement, but working on the gum that was already on it.

Ben’s Chewing Gum Art by Rahid (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Ben was not the first or only one with the idea to make unsightly lumps of gum garbage into something more interesting. In Seattle, the Market Theater at Pike Place Market was fighting against constant gum wads stuck on its wall. Despite continual cleaning, the gum just kept coming. Eventually, they embraced it and became the centre of a world famous Gum Wall, now grown into a gum alley, a destination for tourists to gawk and drop their own gum.

Gum Wall, photo by Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

In Coyoacan, a cool neighbourhood of Mexico City, I saw something similar while visiting some years ago. The chewing gum tree sprang up out of nowhere- a single tree in a hip neighbourhood is now an official gum receptacle, drawing chewed up contributions from visitors from all over the world.

Gum Tree, Mexico City, photo by Lorette C. Luzajic

This impromptu art, or the recycling efforts of dedicated artists who use gum discards as their materials, may be the only solution we have to a sticky situation. Unlike most foodstuffs that enter our mouths, gum is not something that digests into biodegradable sewage. It’s an unfood that humankind adores, and there’s nowhere it can really go.

“What is it?” Jerry famously asked about chewing gum in his stand-up prefacing the Seinfeld episode, “The Gum.”

“I think gum is one of the weirdest human inventions! It’s not a liquid, it’s not a solid, it’s not a food. What is it? It isn’t really anything, you know. I mean, it’s like a stationary bike for your jaw.”

What is it, indeed. Whatever it is, we love it.

It’s difficult to pin down exact and accurate statistics for chewing gum and bubble gum, but most market sources online quote around 30 billion USD annually. That’s at least 100 thousand tonnes of the sticky stuff, or around 375 trillion sticks of chewing gum!

Mars (Wrigley) and Cadbury (Trident, etc) are the largest corporations in the gum biz, with at least 60% of the world market between them. And while Americans love chewing gum, and invented chewing gum as a commodity or packageable product, they don’t love gum per capita as passionately as it is loved elsewhere. Iran is the country that chews the most gum per person, with an 180 million dollar market. 82% of Iranians chew gum. In Saudi Arabia, it is 69%. (By contrast, in America “only” 59% chew gum.)

But what is chewing gum, and why do we love it so much?

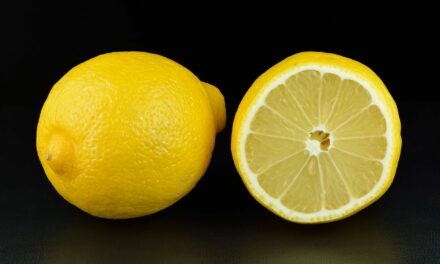

Chewing gum is a food product not meant to be swallowed, but to be masticated inside the mouth for several minutes and then spit out. Gum lovers say they find the chewing habit relieves nervous tension, cleans the teeth, energizes and refreshes, and freshens breath. Bubble gum is a larger sized wad manufactured with enough elasticity to chew and blow rubbery bubbles.

While blowing bubbles adds a great deal to the fun factor of the gum experience, bubble gum or candy gum is not as popular as regular chewing gum. Most chewing gum is sugar-free or has less sugar than bubble gum, and users perceive it as something beneficial for oral hygiene and health.

Chewing gum does impart tangible health benefits. Although the sugar can negatively impact oral health, low and no-sugar gum increases saliva and helps clean food particles from teeth. The chewing itself increases circulation to gums and the mouth. Chewing gum exercises the jaws and other facial muscles and aids with circulation of the head and brain! Chewing gum positively impacts mood and brain health due to increased circulation, as well as helping to keep mouth healthy through saliva production and cleaning mechanisms as gum removes food particles from hard to reach crevices of the teeth. Saliva aids in enamel remineralization, making teeth stronger. The extra saliva production can also naturally assist the processes of acid neutralization in the esophagus, minimizing indigestion or heartburn after a heavy meal.

It’s not all good news, however. Chewing for any length of time beyond actually eating is biologically unnatural, or “parafunctional.” Persistent chewing wears down the temporomandibular system, stressing the muscles, ligaments, and bones of the mouth and jaw area. Occasional chewers need not worry, but those with a “habit” should think again. To get the most out of the benefits of chewing gum without harming the jaw, cap your chew sessions at fifteen minutes or so, no more than a few times a week. Think about gum on an “as needed” basis rather than a routine.

But parafunctional chewing is a minor concern compared to the terrible answer to Jerry’s question. “What is it?” Well, modern, commercial chewing gum is basically plastic! Just a few of the possible ingredients you are chewing with every stick include butyl rubber, paraffin wax, petroleum wax, polyethylene, polyvinyl acetate, elastomers, and more. That’s not mentioning the succulent and sensational sweeteners- sorbitol, sucralose, mannitol, aspartame, glycerol, acesulfame K, xylitol, and butylhydroxytoluene, something also used in embalming fluids.

Bubble gum is manufactured with even more of the stretchy stuff to allow for the novelty of blowing bubbles. Styrene-butadiene, which swells when mixed with saliva, or butyl rubber are key ingredients. They’re also used to make inner tubes and hula hoops. Yummy!

All of this artifice means that gum disposal is a public waste concern all over the world.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

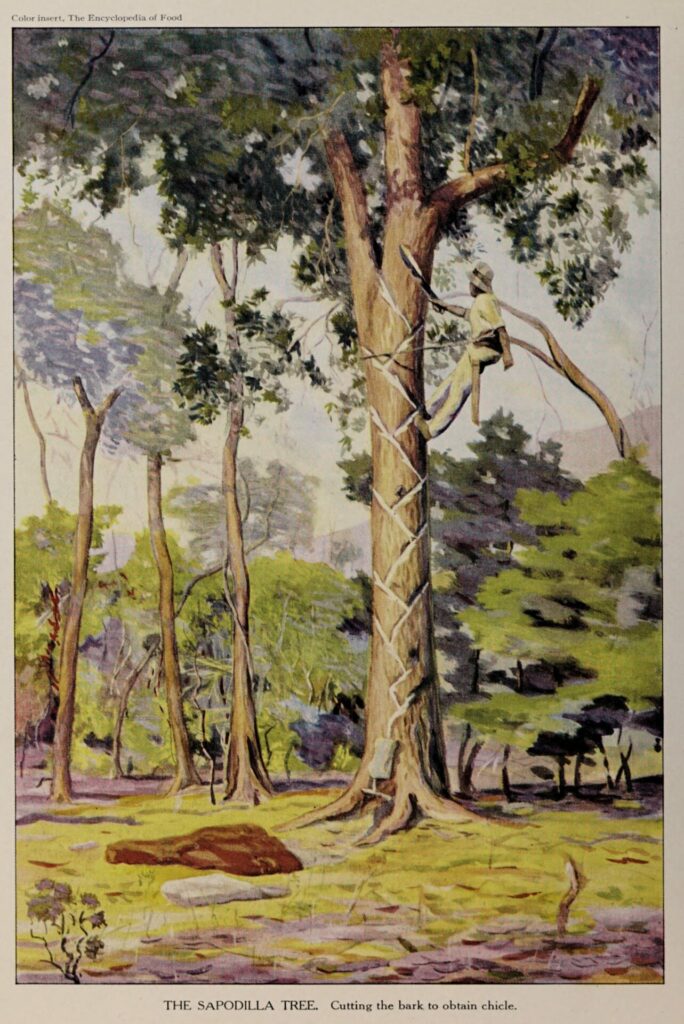

Chewing gum for pleasure and medicinal purposes is nothing new. Commercial chewing gum has a few different invention stories, with several like-minded folks in the mid 19th century each attempted to create a marketable product. First up was John Bacon Curtis, who added paraffin and some flavours to spruce resin to make State of Maine Pure Spruce Gum. Amos Tyler patented chewing gum first 20 years after the spruce chewables were already on the market. He didn’t do anything with his piece of paper, but later that same year, 1869, dentist William Finley Semple patented another gummy chewing recipe- this time made of charcoal and chalk. Between the Pure Spruce Gum and the patents, chewing wax was being sold- this stuff was dipped into powdered sugar for flavour. John Colgan, a pharmacist, created chewy mouthfuls of balsam resin powder combined with sugar. He also began making gum with chicle, a chewy sap from Latin American sapodilla trees. Mayan and Aztec people had been chewing chicle resin for hundreds of years. But Colgan and some of his employees patented ideas for machines that manufactured squares of gum and gum stick wrappers.

Things really took off, however, for gum, when Mexico’s president brought some chicle to New York as a substitute for rubber, and gave it to business man Thomas Adams. Chicle failed to stand in for other products, but Adams was soon reimagined as The American Chicle Company. (The brand “Chiclets” is from the word “chicle.”)

William Wrigley was a masterful advertiser. In 1893, when he introduced Wrigley’s Spearmint and Juicy Fruit stick flavours, the marketplace was already crowded. He became one of the top gum brands in the world, to this day, by giving away his products and cementing enthusiastic customers this way.

A little later, along came Walter Diemer and Frank Fleer, who worked out the big bubble. First up was Fleer’s model, Blibber Blubber, in 1906, but it was too sticky to take off. Diemer kept tinkering with Fleer’s idea, and in 1928 Dubble Bubble was born. Dubble Bubble is the reason we associate bubble gum with the colour pink- they wanted to stand apart from regular chewing gum, and pink food dye was the only colour available to them at the time.

By the time bubble gum was everywhere, however, the bubble was already bursting. The mass consumption of chicle chews was having a devastating impact on the Central American ecosystem. By the 1930s, a quarter of the trees were gone. Gum makers sought alternate substances to chew and found great success with synthetic ingredients. Few consumers question, or curtail, what they’re chewing, even though most of us have a vague understanding that it is completely unnatural.

Indeed, novelty chews are popular party favours and treats. While mint and cinnamon varieties to freshen breath and clean mouth are the main market, chewing gum and bubble gum also comes in strips, ribbon, tape, cigar-shapes and classic gum balls. It comes striped and candied, or with liquified centres. It comes popping and fizzing. It comes in neon shades and bright blue, yellow, purple, green, orange- and black. There’s mint galore, and also raspberry, mango, pomegranate, cotton candy, sour citrus, cloves, licorice, watermelon, and pumpkin spice. If you’re looking for a gag gift you might choose meatball flavour gum balls, TV dinner, wasabi, cocktail weenies, and pickles. The most beloved of all gross gum go-to’s is, of course, Thrills. Canada’s purple mouthfuls taste like mothballs, or, as the ad slogan promises, “still tastes like soap.”

Yesterday’s people would not recognize our current conundrum of undigested, non-biodegradable gunky rubber gobs, masticated and stuck to every streetcar pole and school desk underbelly. But they totally get the urge to chew, as an anxiety-reducing pastime and an oral hygiene helper. Humans all over the world have been putting various tree saps and resins into their mouths. We attribute gum’s origins to Mayan and Aztec chicle chewers, because their chewing gum trees are close to home. But they weren’t the only ones with the bright idea to chomp down on chewy resins.

In the Middle East, Boswellia resin was chewed for medicinal effects. In Africa, dried kola nuts were chewed to release sweetness and a stimulant kick. Mastic tree bark was chewed by Greeks, giving us the word “masticated.” Native Americans gleaned the good stuff from spruce sap (an idea that John Bacon Curtis ran with to make his spruce gum.) Other gums and resins the world over have shown up as chewing gum. The oldest known gum so far was found in Denmark, a wad of birch tar. Modern archeological testing told us quite a bit: the gum had been chewed approximately 5700 years ago, by a young blue eyed, brown haired girl whose recent meal consisted of duck and hazelnuts.

If chewing gum relics of the Stone Age can still speak volumes across the millennia, what will our habits say about us to future citizens? Will we have gone back to sanity and found a way to make chiclet trees sustainable gum givers? Or will the world be covered in an indestructible “coral reef” ofsynthetic rubbers and layers of masticated petroleum? Will we be in our flying cars, dipping under neon coloured hubba bubbles, or long drowned in the stuff?

Well, maybe. Pop goes the world.

Lorette C. Luzajic

The sapodilla tree, illustration from The Encyclopedia of Food by Artemas Ward, 1923