JJ Harrison (www.jjharrison.com.au) CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

“My final, considered judgment is that the hardy bulb garlic blesses and ennobles everything it touches – with the possible exception of ice cream and pie.”

Angelo Pellegrini, The Unprejudiced Palate, 1948

In the 1946 classic holiday film, It’s a Wonderful Life, a guardian angel visits George Bailey, a man weary of living, and shows him how he can find meaning and purpose by simply looking back more carefully through his ordinary life.

One famous line from the film may be confusing to contemporary viewers. In a scene where Bailey is asking a banker for a loan, he is denied and berated for being “trapped into frittering his life away, playing nursemaid to a lot of garlic eaters.”

“Garlic eaters” was a pejorative reference to Italian immigrants, one reserved for those perceived as the lowest of the low. While today Italian cuisine is nearly universally revered as delicious, at the time, newcomer Italian families were low-wage labourers and their culinary habits were derided as ignorant and stinky.

This dreadful ethnic slur goes way back, winding through cultures and centuries to mock and degrade Italians, Jews, Hungarians, Romanians, French, Koreans, Chinese, Polish, Russians, and Spanish people and their dishes. For some Protestants, the “Papists” were garlic eaters. In Shogun, the historical epic by James Clavell, the upper crust Japanese condemn Koreans for their robust, spicy fare. In Hindu cultures, garlic is believed to be too stimulating, resulting in people who have unruly libidos and think irrationally.

Shakespeare hits the nail on the head and names the real target in his play, Coriolanus: “The breath of garlic-eaters! You’ve done it now, you and your lowly laborers, you tribunes that carried on about the votes of the working, garlic-eating common man!”

Bingo. The condemnation of garlic eaters is a class concern. It was all about the peasants, and their smelly foods. In Italy itself, the rich Italians looked down on the garlic eating Italian peasants and their common ways.

In a short story from the 15th century collection, Novelle Porretane, Giovanni Sabadino degli Arienti wrote, “…There was a very beautiful woman, representing Virtue, holding her nose and covering her mouth to show that she was disgusted by the smell of garlic.”

Virtue and nobility despised the stinking rose. Garlic was associated with promiscuity, poverty, and superstition. It was not fit for the patrician upper crust.

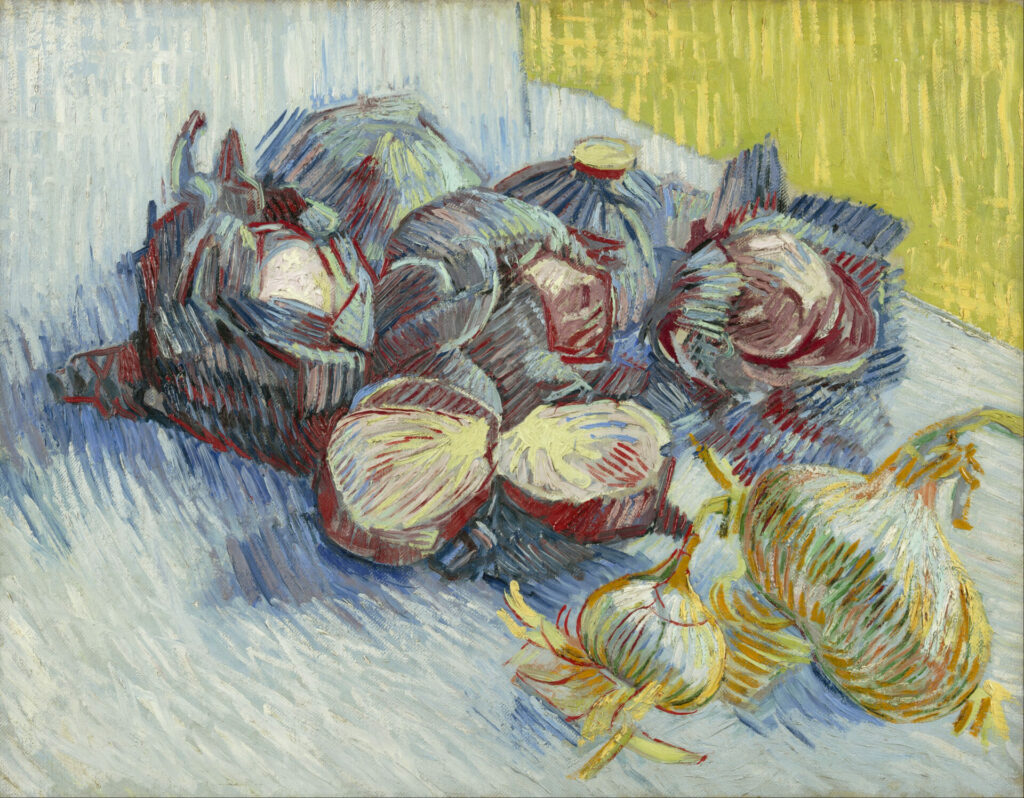

Red Cabbage and Garlic, by Vincent Van Gogh (Netherlands) 1887

Garlic is a hearty plant that can grow in many climates, including cold ones. It has many fewer enemies in weather and pestilence than most crops, and keeps nicely for weeks or months at a time. These factors made garlic accessible to the common classes throughout the world. As with other intensely scented and flavoured foods, such as sardines, herring, cabbage, and onions, the pampered people sneered down their noses at those who ate them.

There was only one problem with the whole “down with garlic” thing.

The damn stuff is delicious. Everywhere garlic was hated, it was also loved.

Spicy Green Beans (with Garlic) by Jeffrey Coolwater via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Deed

As Ryleigh Nucilli writes in Atlas Obscura, “For the 16th century Italian noble, garlic posed a unique, culinary dilemma. To demonstrate status, a person of taste and means served food prepared with the finest, rarest spices, such as saffron, cinnamon, cloves, and ginger. Common ingredients were to be avoided, and garlic was neither rare nor fine. But it was delicious. So what was a noble lord or lady to do?”

Where there’s a problem, there’s a solution! Nucilli goes on to tell us about the tradition of “ennobling” base ingredients like garlic by mixing them with rare and rich spices and the finest meats. Voila, crushed garlic and seasoning marinades for poultry and game!

Today, no sane chef, peasant or aristocrat, would shun garlic, one of the global kitchen’s most essential ingredients. It’s tough to describe the stuff: it is pungent, sharp, and spicy chewed raw, and mellow, sweet, and buttery when cooked. It marries disparate flavours and completes soups, meats, sauces, and salads. It pairs extraordinarily well with lemon, or tomato, or basil, or olives, or chiles, or ginger, or all of the above. It is a pillar of Chinese, Indian, French, Jewish, Italian, Greek, Persian, Portuguese, Polish, Mexican, and Moroccan cooking, to name a few.

Tzaziki, by Nikodem Nijaki, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

There are at least 600 kinds of garlic, or Allium Sativum. It appears to have originated in the areas of Central Asia and eastern Iran, but it is everywhere. It’s not easy to trace the story of garlic, because it has always been there. At the beginning of recorded history, garlic is everywhere, in Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and beyond.

Garlic was valued for medicinal properties in every region it is was known. Garlic has anti-viral, anti-fungal, and antibacterial properties, and though ancient populations didn’t know the science of germs and pathogens, it seems they understood something about these conditions instinctively, perhaps through simple observation. Garlic was believed nearly universally to cure numerous diseases and bolster stamina and virility.

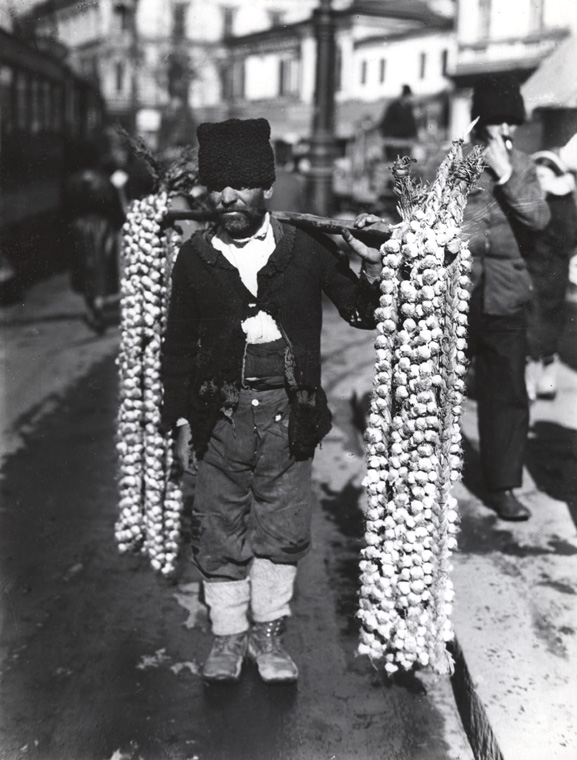

Garlic Seller, Romania, by Nicolae Ionescu, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Perhaps the most important and widespread use of garlic is a surprise: it wards off vampires.

The legendary magic of garlic to scare the undead is not an obscure conviction conjured by the fictive imagination of Bram Stoker. Rather, his allusions to garlic’s protective powers were drawn from literally millennia of beliefs. Braids of garlic have been draped over caskets and corpses for as far back as we can remember. In ancient Mesopotamia, cloves were placed in the mouths of the dead prevent their bodies from being taken over by evil spirits. Throughout the Mediterranean and eastern European regions, bulbs of garlic could ward off the curse of the evil eye. Garlic has been used as apotropaic magic for as far back as we can recall, in multiple cultures, warding off all manner of evil spirits, curses, diseases, monsters, predators, and even werewolves and burglars.

Followers of the Egyptian underworld god Sokar wore garlands of garlic to fend themselves from evil spirits. In ancient China, garlic was offered at New Year’s as a gift to the deities. It was then eaten or posted to prevent bad luck. In Korea, eating garlic was believed to ward off tigers.

Far away from Transylvania, in Mexico, was the Aztec tlahuelpuchi, a cursed bloodsucking shape shifter that took the form of a human but flew around after dark eating babies. Garlic was said to protect homes and sleeping infants.

Garlic at Franke’ly Delicious Niagara Farm, photo courtesy of Moshe Sakal

Garlic was sometimes associated with the devil itself. In some ancient legends, “the devil’s footprints” depict Lucifer turning his back on God. In his footsteps, garlic and onions grew forth from the ground. Yet garlic is revered in the kitchen, medicine cabinet, and as an amulet for protection throughout the Middle East, Europe, and wherever the Abrahamic religions have gone.

The devil’s footprints legend brings to mind an even older story in Hinduism, where Lord Vishnu the demon slayer beheaded the evil spirits Rahu and Ketu. From the place where their blood was spilled, garlic and onions sprang out of the earth. Garlic is considered tamasic and rajsic in Ayurveda, or Hindu medicine and philosophy. This means it will overstimulate the body and mind and we should be wary of overconsumption. Some devout Hindus and Buddhists as well avoid garlic for this reason. Yet garlic is considered a powerful remedy against disease, and it is part of the essential trilogy that defines a majority of Indian cookery- garlic, onions, and ginger.

The dichotomy of good and evil in the ancient world was complex rather than black and white. Deities and demons alike were both good and bad fortune simultaneously. A particular spirit might bring good luck in one circumstance and bad luck in another. Evil itself was often considered powerful over stronger evils. In this context, we can understand why certain superstitions or customs appear to be contradictions.

Franke’ly Delicious Niagara Farms. Photo courtesy of Moshe Sakal

In the Balkans and eastern Europe, it is customary to this day to have ropes of garlic in homes, barns, and gardens, dispelling dangerous strigoi. This kind of undead spirit or witch had various incarnations, from bat-like flying creatures to gnarled old women. They craved cow’s milk in some stories, and so garlic was rubbed over cows and posted in barns. In other legends, they ate children or craved their blood, so garlic bulbs were common decorations in nurseries. Moroi were a kind of spirit that could overtake the energy of a living person, and to this day garlic ropes are important protection, especially around the feast of Saint Andrew, patron saint of Romania, later this month.

We come back to Dracula in 1897, full circle. These Carpathian mountain traditions are literally as old as the hills, and that is where Stoker found them.

Indeed, the word “allium” is linked by some sources to both Celtic and Sanskrit origins, a term that means “slayer of monsters.”

Garlic Soup, by Jules Morgan from Montreal, Canada, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

However fascinating, the folk beliefs and superstitions surrounding garlic may seem strange and farfetched to the modern mind. But they exist alongside equally strong convictions in garlic as medicine. Eons before the immunomodulatory, antimicrobial and anticancer abilities of garlic were confirmed by science, the garlic bulb was an important part of numerous cultures’ medicine bag. It was a first line of defence for every conceivable ailment, from hemorrhoids to snakebite to parasites to erectile dysfunction to TB to the plague. It is reasonable to conclude that the fact that garlic was so successful as a tonic and remedy for many illnesses helped solidify its reputation for keeping evil spirits at bay. After all, in the old world, everything was filled with spirits. Everything was personified as a kind of being. Everything from the weather to household objects was animated. Mental illness was famously perceived as demonic possession, and disease was also caused by evil spirits. This was not just the belief of Catholics of the middle ages, but throughout the great early civilizations of Mesopotamia, Africa, Persia, and the pre-Columbian North and South Americas. It makes sense that garlic became a “medicine man” in all of his hats throughout folk customs everywhere.

Winter, by Lucas van Valckenborch (Belgium) c. 1595

A favourite scenario from the popular Seinfeld sitcom poked lighthearted fun at the age-old, widespread use of garlic as apotropaic magic. While George is trying to convert to Latvian Orthodox to impress a girl, goofy Kramer finds himself the object of affection of the church’s Sister Roberta. He tells Jerry that he picked up on a vibe. When Sister Roberta starts pursuing him, he seeks help from the priest, who tells him he has “the kavorka,” a made-up word that is now part of the international lexicon, meaning “the lure of the animal.” The priest acknowledges, “Women are drawn to you. They would give anything to be possessed by you.” Kramer tells Jerry, “I have this power. And I have no control over it… I’m dangerous, Jerry, I’m very, very dangerous!”

To repel the women in thrall to his kavorka, Kramer is told to wear a garlic necklace and bathe in vinegar.

But if evil spirits cannot withstand the olfactory qualities of garlic, the rest of us are mere mortals and cannot help being seduced by the sharp, savory, indescribable flavour garlic imparts. The unpleasant smells take place later, with chemical changes producing a range of ugly scents that come through our breath and seep out of our pores hours after the fact. In the heat of the moment, most of us ignore the repellant fragrance we will give off later and give in to immediate gratification.

As Michael Franti of Spearhead sang in “Red Beans and Rice,” “The way to my heart…is with a garlic clove…It smells hella sexy… when it’s on the kitchen stove.”

The sensation scent of thin slices of garlic sizzling in butter or bubbling in a sauce with basil and black olives is irresistible. For almost everyone who cooks at all, garlic is the bedrock of the kitchen. It’s the first thing we reach for.

Honey Garlic Chicken Wings, by Sue Thompson via Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0 Deed

The classic creamy pleasure of a good Caesar salad depends on a garlicky kick. It is ideally paired with delicious warm garlic bread.

And who doesn’t go gaga over the sticky sweet paradise of honey garlic wings?

Pesto is bliss: that green goddess muck from Genoa is a perfect harmony of pine nuts, basil, and garlic. Indian masala is the double thunderbolt of ginger and garlic.

Greek style potatoes, grilled souvlaki meats, and horiatiki village salad must be accompanied with generous tzatziki on the side, a thick white sauce made of yogurt, garlic, and cucumbers.

The Romanian table is naked without mujdei, a simple emulsion of crushed garlic and oil, often with lemon, paprika, and salt.

Serbian and Macedonian ajvar is a red pepper and garlic paste for bread or meats.

Korean kimchi is a fermented cabbage salad with chiles and garlic, served with everything.

Any Lebanese-style shawarma wrap worth its name comes drenched in a sauce that is a veritable garlic bomb.

The national dish of the Philippines is adobo chicken, a sticky sensation of garlic, soy sauce and vinegar.

Argentina’s green salsa, chimichurri sauce, is hopelessly addictive, a heavenly crush of cilantro, green herbs and garlic.

In Afghani cuisine, chile, garlic, and onions are behind everything, including melt-in-the-mouth eggplant, Banjaan borani.

A famous French classic is popular all over the world, chicken with 40 cloves of garlic.

Everyone adores Chinese chili garlic sauce, the tangy spicy must-have condiment for stir-fries, soups, and rice.

New Orleans style garlic soup is a long-simmered affair that uses over two cups of garlic- at least four heads of cloves!

And then there’s aioli, a Mediterranean-style mayonnaise heavy on the garlic that makes everything better.

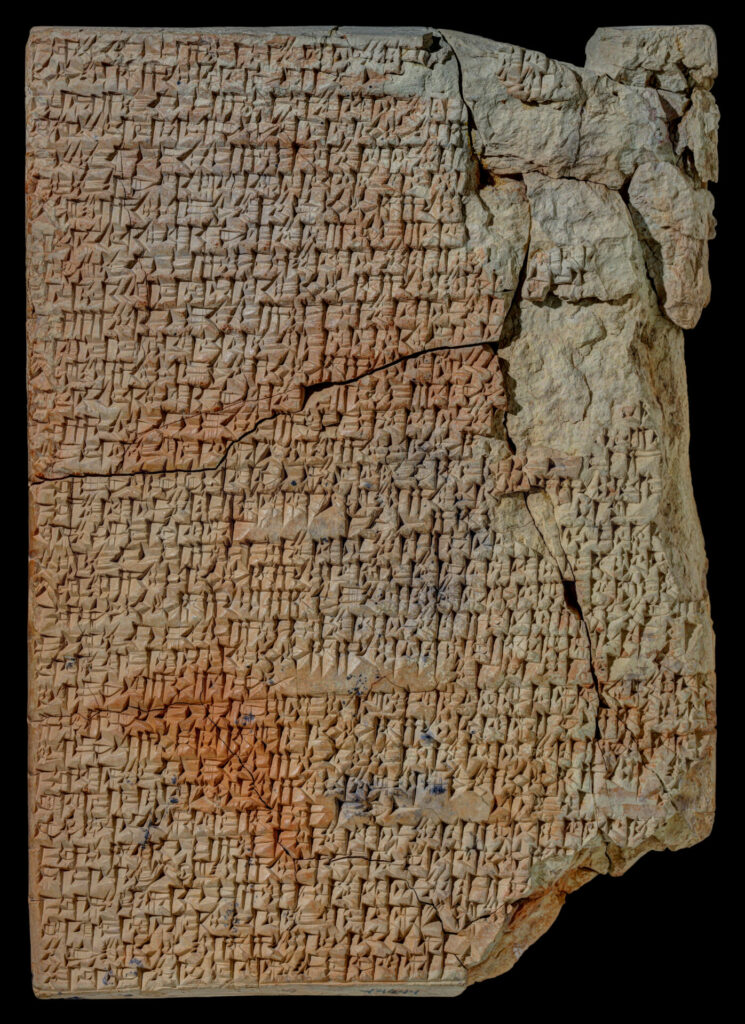

In the beginning, there was gazelle stewed in garlic and broth- some of the oldest known recipes in the world, from Babylon in 1900 BC, used garlic.

Yale Culinary Tablets (“Mesopotamian Cookbook”) by Kwag1980, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Garlic eaters are everywhere, and always have been.

Angelo Pellegrini was a lit professor who wrote books about his passion for food and the experience of Italian immigrants to America, and one of this best loved books is his 1948 memoir and cookbook, The Unprejudiced Palate. He concluded that garlic “blesses and ennobles” everything, “with the possible exception of ice cream and pie.”

But Pellegrini got it wrong.

Garlic ice cream is a popular novelty at garlic festivals from Toronto to Finland. The best is a creamy sweet-savory blend that balances artfully on the palate. It’s marvellous.

Garlic Ice Cream, by Eugene Kim via Flickr CC BY 2.0 Deed