Erratic and extreme weather episodes have become the new normal in vineyards around the globe. The once considered “ideal growing season” for many regions, with moderate rainfalls at judicious periods and overall dry, sunny, warm (but not hot), conditions lingering into the Fall, seem implausibly idealistic now.

So, what makes a successful growing season in today’s world? Two years ago, I reported on the terrible 2021 growing season conditions in France. Widespread spring frosts ravaged vineyards from Chablis to the Languedoc. Violent hailstorms struck the Loire and the Côte d’Or, among other areas. Fungal pressure was sky high in the northern half of the country due to regular July rains.

Unsurprisingly therefore, the Bourgogne 2021 vintage received middling scores. And yet, on a recent trip to the region, many of the 2021 wines were tasting beautifully. At Domaine Benoît Droin, in Chablis, I did a comparative tasting of 12 different climats from the vintage. They all had those classic hallmarks of great Chablis – racy yet balanced acidity, overt minerality, great tension, and lots of lift.

At Domaine Taupenot-Merme, in Morey-Saint-Denis, the 2021 range displayed all I love from top Côte de Nuits. Already approachable, they were vivid, perfumed, silky, and complex. There was an ethereal quality to them, with no lack of structure or depth.

Of course, these are two top estates with vineyards in the most favourable terroirs. There were leaner, sharper wines from some of the more modest, often cooler, sites. Overall though, 2021 surprised me with its finesse and easy drinkability.

In comparison, the 2020 vintage is a behemoth. The wines are almost black in colour, with powerful, concentrated palate structures, heady fruit, and alcohol levels regularly over 14% – some at 15%. Surprisingly, for such a dry, sunny vintage, the wines are reasonably fresh and harmonious. The tannins are imposing, but sufficiently ripe to soften well over time.

The 2020 vintage is being hailed as a triumph by growers and critics alike, notably for its long-term ageing potential. The fact remains though, that they are hard wines to drink today and will be for a number of years. The 2021 vintage – sadly a miniscule one in terms of quantity – offers far more immediate pleasure.

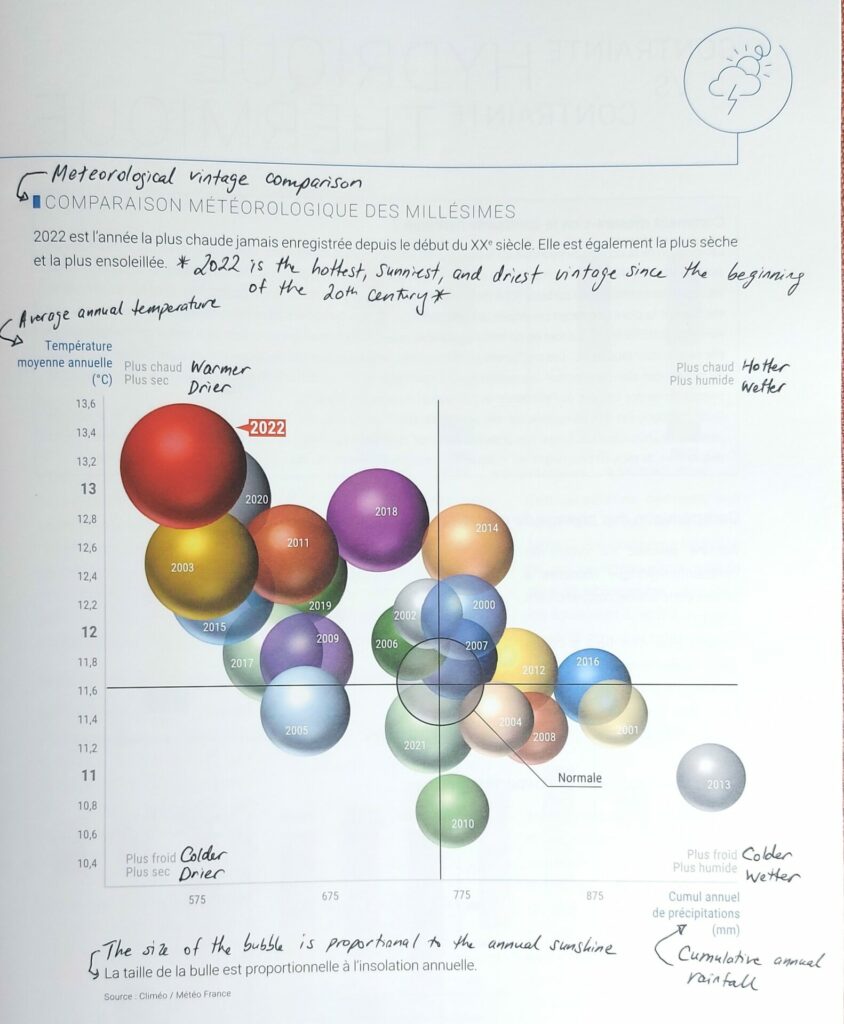

The Bourgogne Wine Board put out a fascinating vintage comparison graphic based on weather patterns, from the 2000 to 2022 growing season (see below). It shows some interesting anomalies. The 2010 vintage, considered one of the best since the turn of the century, is one of the least sunny and the coldest. The 2016 vintage, also widely admired, is one of the wettest on record.

Photo credit: Bourgogne Wine Board

It just goes to show how difficult it is to judge a vintage by its weather patterns. How many times has warm weather in late August and into September saved a cool, potentially under-ripe vintage? How many times has cooler nights later in the season helped to preserve acidity in overly hot years?

I remember chatting with an Ontario wine producer a few years back. She called growing grapes in Niagara “extreme viticulture” due to winter kill, frost, hail, pest pressure, and high summer humidity. These days, the term is certainly apt for Bourgogne as well.

While tasting with a Vougeot producer last month, his son arrived to inform him that one of their parcels on the Côte de Beaune had suffered a brief, yet violent hailstorm, with estimated damage to 70% of the crop. He just shrugged his shoulders sadly and carried on with the tasting.

In Bourgogne, things are changing at a faster pace than I have ever previously witnessed. Growers are having to adapt practices in the vineyards and in the cellar, every vintage. In the past, many winemakers seemed to have quite a formulaic model, by appellation tier, for fermentation and ageing.

Recently, I have heard far more considerations given to vintage. Decisions like use and percentage of stems, whether to cold soak, temperature of fermentation, level of extraction, amount of new oak, use of alternative vessels, all seem to vary far more widely from one vintage to the next in the pursuit of balanced wines in an ever-changing climate.

In the vineyards, growers are working hard to find ways to delay budbreak past punishing spring frosts, to shade vines and keep them cool in overly hot, sunny conditions, to fight high fungal pressure effectively without recourse to harmful chemicals.

Perhaps a measure of their success is the number of excellent recent vintages, despite such widely divergent growing seasons.