Greenville 6 ft Nutcrackers in O.P. Taylors window 2010 Public Domain

A Tough Nut to Crack: a Nutcracker Suite

I was a tween, around Clara’s age, when I unwrapped my own nutcracker prince from under the Tannenbaum.

Christmas was, and is, practically synonymous with The Nutcracker, a kind of literary fairy tale by E.T.A. Hoffman that Pyotr Tchaikovsky spun into a famous ballet. I was mesmerized by the brutal beauty of tip-toe dancing, and sometimes bound my big, flat feet with masking tape and pretended to be a prima ballerina- a requisite rite of passage, perhaps, for young girls. But my main curiosity and fantasy was not about the transformation from statue to living man, or about the prince, or about everlasting love. I was born an objectophile, enchanted most by artifacts, by art. It was the thing itself I wanted so badly- the wooden, German-crafted nutcracker doll. I have always felt that handmade things were alive in their own way, bearing interwoven histories that bear witness to surprising stories of the human experience.

Germany has woodcarving in its blood. My ancestors are legendary, going back centuries, for their carpentry skills. This manifests in pragmatic ways with sturdy, quality house-framing, and cabinet-making. My grandfather built from scratch, with his bare hands, the majestic Swiss Chalet house I grew up in, on a bedraggled orchard property. This, after coming to Canada with nothing. More recently, my nephew raised a massive two-storey barn in his backyard as a summer project.

German Smoke Men and Nutcracker, by Dietmut Teijgeman-Hansen via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Deed

But it is the offbeat oddities for which the whole world knows us: elaborate cuckoo clocks, intricate religious figurines, spinning folk art candelabra with o-mouthed angels, stout statues with ruddy cheeks and bristly beards that puff incense smoke from their pipes and nostrils. The hallmark of German woodwork is a unique blend of folksy naïve qualities with impeccable craftsmanship. They are beautiful, and weird.

Our chapter of the nutcracker story began in the Erzgebirge mountains of Saxony in east Germany. These once remote mining villages brought metallurgy from the bounty inside the hills, and woodcraft from the gifts of the surrounding forests.

We picture gruff and rugged miners, in the ambiance of snowy woods and mountain peaks, whittling and carving nutcracker figurines and nativity shepherds and camels. It’s seemingly a world away from the Halloween werewolf legend brought to life by Michael Jackson back when I was mummy-swaddling my toes to play Clara under the Christmas tree. But Jackson often told the tale of how his Thriller album, centered around the campy title graveyard fantasy, was inspired by Tchaikovsky’s 1892 Nutcracker Suite.

He famously told Ebony Magazine, “Ever since I was a little boy, I would study composition…And it was Tchaikovsky that influenced me the most…If you take an album like Nutcracker Suite, every song is killer. I said to myself ‘why couldn’t there be a pop album like that where every song … was a hit song?”

The Russian composer was not as thrilled as Michael was with his ballet suite. Tchaikovsky was even more of a perfectionist than Jackson, and known for his volatile, tempestuous emotions towards his own music. He often destroyed his scores, deeming them unworthy. Though the artist wasn’t wholly pleased, the suite found favour with its audiences. But the whole Nutcracker as a ballet was considered too childish and fantastical. It did not become popular until it was performed in America, where it has been an essential part of Christmas festivities since mid last century.

Photo of 1892 production of The Nutcracker in St Petersburg. PUblic Domain.

A quarter century or so later, released 41 years ago (!!!!) Thriller was the world’s best-selling album by the end of its first year, and has remained in top place ever since. Though we sometimes associate Thriller with Halloween or with horror stories, not with sugarplum fairies and sleigh bells, Jackson’s Nutcracker-inspired goal was to create a complete and varied experience by arranging a variety of perfect songs. It was a plan that paid off in spades.

If Jackson was influenced by ballet and by musicals, as well as by horror stories and cinema, Tchaikovsky’s score was inspired by Alexandre Dumas’ more sanitized retelling of Hoffman’s 1816 fable, Nussknacker und Mausekönig (Nutcracker and Mouse King.) Ernst Theodor Wilhelm “Amadeus” Hoffmann was also a composer, and a painter, and a writer. He was a Romantic storyteller who rejected the rational rationale for art, preferring to conjure the darkness and mystery that he believed was the true heart of human imagination. While Hoffmann’s is hardly a household name, his horror stories are widely known. The Nutcracker, of course, but also The Sandman and others. His stories influenced everything from The Matrix to The Twilight Zone to Edgar Allan Poe.

It is only with modern eyes that Hoffmann’s horror story nutcracker should be a surprise. In their German originals, all of our Disneyfied tales were truly macabre, with gruesome and grisly folklore at their core. The nutcracker dolls that today are all heroic princes and soldiers were not always so. If some retain their creepy ghosts of Christmas past, with their big leering teeth and deadpan stare, that is because the first ones were created as apotropaic totems, meant to frighten malevolent spirits away. In the mountain villages, mining and lumber life was extremely harsh, and the peasants had precious little with which to defend themselves against the darkest gods.

17th Century Nutcrackers, Germany, from Nutcracker Museum, photo René Röder, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The first Erzgebirge nutcrackers looked much different from the stylized, standing soldier variety. Throughout parts of Europe, there were plain carved wood nutcrackers made to look like people or animals. In the mountains of eastern Germany, crafting them served several purposes. They were good luck charms of protection against evil. They could honour the animals of the region, or the life of peasants. Many figures were of miners, cheesemongers, chimney sweep, shoemaker, or other humble positions of village life. They could be satirical, too- sometimes the rich and powerful were mocked with ugly caricatures.

The nutcrackers could be sold by travellers to earn a few dollars at open doors along their journey. Creating them helped families pass the time together and develop new skills when work was in short supply, or when the weather was inclement. And perhaps most commonly, they were very popular gifts. The association with gift-giving is one way they first became associated with the Christmas holidays. Another way, that also popularized the soldier model from Hoffmann’s tale, was that allied soldiers bought them during their time in Germany as souvenirs and holiday presents.

The art of the nutcracker eventually became an important export of German artisans, with multigenerational nutcracker houses upholding traditional creation methods for Christmas markets all over the world today.

Nutcrackers at the Christmas Market, photo by mcfarlandmo CC BY-NC 2.0 Deed via Flickr

But of course, we are missing the most important purpose of the nutcrackers. It’s easy to forget in today’s realm of decorative Dollarama nutcracker tree ornaments and ballet performance matinees, that the original nutcrackers served an essential purpose. What was that?

Why, to crack nuts, of course.

When we can so easily buy cashews, hazelnuts, and almond slices, already shelled, in handy portions, it is difficult to appreciate the gravitas of the nut conundrum in our past. Even if we do opt to crack whole nuts ourselves, it is more of a quaint tradition than a dire need. After all, we probably have a classic and simple stainless steel tool from Home Sense or Canadian Tire on hand. Maybe we mislaid it once, between winters, and had to venture away from the fire and holiday music momentarily and fork out a few bucks for a replacement. But once upon a time, there was a major obstacle between us and the nutritious, delicious nuts we desired and depended on. Many nuts were too tough to crack, even when we were willing to risk our teeth for the cause.

Classic and simple Tablecraft model for cracking nuts- the one we all have!

Germany yielded walnuts and chestnuts, and had access to walnuts and hazelnuts. But these nuts did not come ready to eat. They had hard shells that required breaking.

This was the same concern of people the world over, not just in the Erzgebirge mountains. The evolution of the nutcracker and the lore that led to its winter ballet is just one chapter of a much longer saga. Long before our handsome prince soldier was awakened, people needed to get at those nuts.

A German solution was to use a wooden hinged lever decorated as a puppet animal or person. Italy, France, and beyond also used figurative decorations for the cause. But hand wrought iron and brass varieties were already used in the 12thcentury in France, too.

Bronze Hands Nutcracker, National Archaeological Museum of Taranto, Attribution, via Wikimedia Commons

Ancient Rome had powerful and elaborate nutcrackers. A massive 14 inch saw tooth bronze lever with twin lions dates back to around 200 BC. And a very unique and ancient model is on display now at the National Museum of Archeology Taranto, Italy. It is a massive bronze statue of women’s clasped hands, complete with gilded bronze bracelet bands.

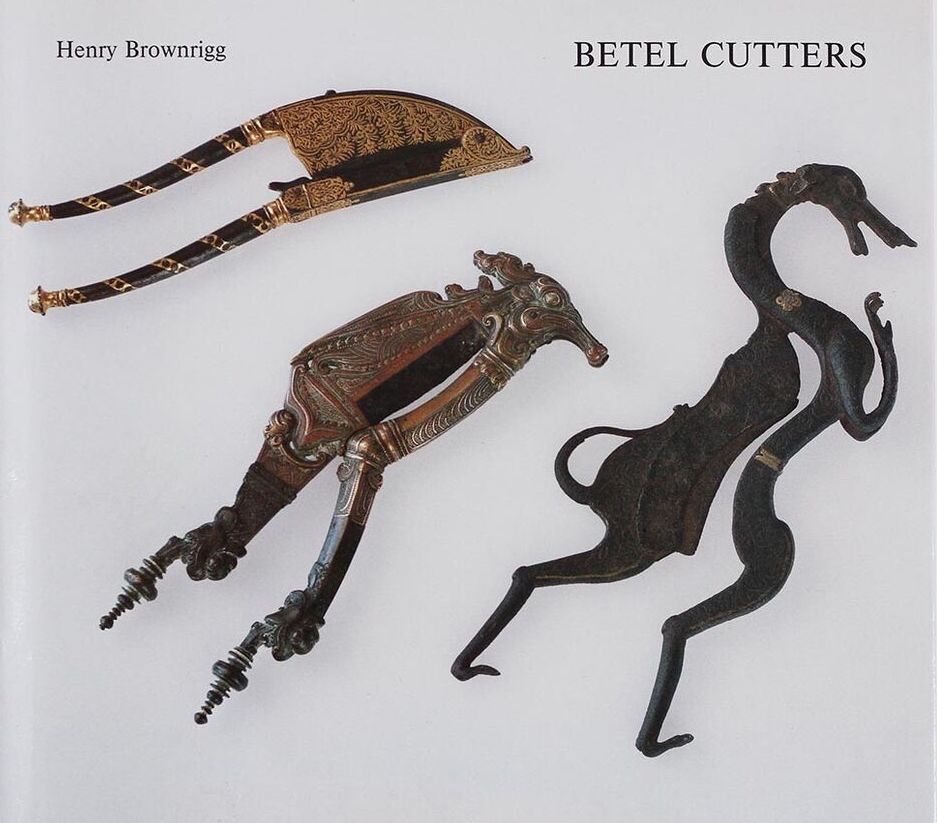

Thames and Hudson book, 1992

In India, nutcrackers are exquisite brass beauties imitating gods and monsters, with dragons and peacocks and hybrid animals. Stunning and strange, antique betel nut cutters are collectible today and have their own intriguing history. Crate and Barrell recently had a delightful and sturdy aluminum cast hippopotamus on offer, now sold out. There are squirrels and alligators and women’s legs, and cast iron tabletop tools that look more like medieval torture devices. The wooden German dolls come today as cops, basketball players, Elvis, Alice in Wonderland, Donald Trump, Snoopy, Day of the Dead skeletons, and Darth Vader.

Crate and Barrel hippo nutracker

We’ve been wrestling with nuts for even longer than these creative solutions show. The earliest nutcrackers are primitive indeed. On every continent, mysterious and prehistoric sets of local rocks with bumpy concave grooves have been found. We call them “nutting stones” given the possibility that the shapes were made from the practice of ramming them against nuts to crack them open. Some naysayers claim that the shape is natural, not man-made. Yet there are ethnographic accounts observing their household use by Indigenous people. There are well-documented tools such as the macadamia crackers used by Aboriginal Australians, that show human ingenuity for using what’s on hand to solve a problem.

Nutting Stone found in Kentucky, photo by Curtis Albert via Flickr CC BY 2.0 Deed

The jury is still out on whether nutting stones are the earliest known nutcrackers or something yet unknown. But we have definitely always used some tool or another to get inside the tough carapaces that nuts love to wear in hopes of avoiding us. Even our primate friends, who have bigger, tougher jaws and stronger chewing muscles, prefer to use tools. Scientists have observed monkeys smashing nuts open with rocks.

When there’s a will, there’s a way.

It was forty years ago that I unwrapped my Erzgebirge totem, a toothy fellow crafted for function as well as art. He was made by people who might be my distant relatives. Although he is a treasure I’ve lost in the passage of time, I’ve never lost the profound thrill of mystery his likenesses instill in me with just a glimpse. A few notes of The Nutcracker Suitetake me into magic, then deep into the hills of my bloodline where I was dreamed up long before the stork dropped me off at Niagara Falls General Hospital. The nutcracker art is a kind of magic, with myths and legends to accompany. The dolls were woven into Christmas by custom and by chance, but fit too into our darker stories.

Go figure. It’s always the stories, that’s the thing. We can’t stop making them up. We charge every object and foodstuff with myth and meaning. We can’t stop imagining and plotting and building folklore and fables around everything, whether it’s how the leopard got its spots, or a macabre tale of terror and battle between a handy kitchen tool that cracks nuts and evil mice that talk.

And then we change the story around again, make it grander, add in some glitter and pointy ballerina shoes. And then we do it again: we sprinkle in some fairy dust and a handful of candy canes and say, Merry Christmas!

Lorette C. Luzajic

**

““Ah! Dear Father! Who owns that darling little man over on the tree there?” “He,” the father answered. “He, dear child, should work hard for all of us. He should crack the hard nuts for us nicely…The father then removed him cautiously from the table and, raising the wooden cape aloft, the manikin opened his mouth wide, wide, and showed two rows of very sharp, very tiny white teeth. When told to do so, Marie inserted a nut and—Crack! Crack!—he chewed up the nut, so that the shell dropped away, and the sweet kernel itself ended up in Marie’s hand.”

E.T.A. Hoffmann, The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, 1816

Nutcracker, 1899, by Theodor Hosemann, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons