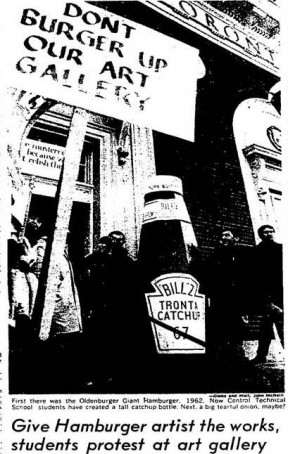

In 1967, there was a fracas outside the Art Gallery of Ontario, with protestors and bullhorns and placards. The alleged injustice that disgruntled Torontonians on this occasion was not police violence, vaccine mandates, or war. Nor were there fires set, looting, or property damage. There was, rather, a nine-foot high bottle of ketchup paraded up and down Dundas. Some locals, in particular art students from nearby Central Tech, were disgruntled about the museum’s recent art purchase, Giant Hamburger, by Claes Oldenburg. The massive floor burger weighed in at 700 pounds and $2000, and burgeoning artists were furious about the tasteless lump of canvas and polyurethane foam.

Arguably, the ketchup bottle had as much social commentary and historical heft as the hamburger, if not more, and merited a place in the hallowed walls of art history, but the museum rejected the donation, dismissing the gift outright because it was not “an important and original work of art.” Oldenburg of the hamburger was himself more generous toward the protest, admitting, “My work is going to get old soon enough.”

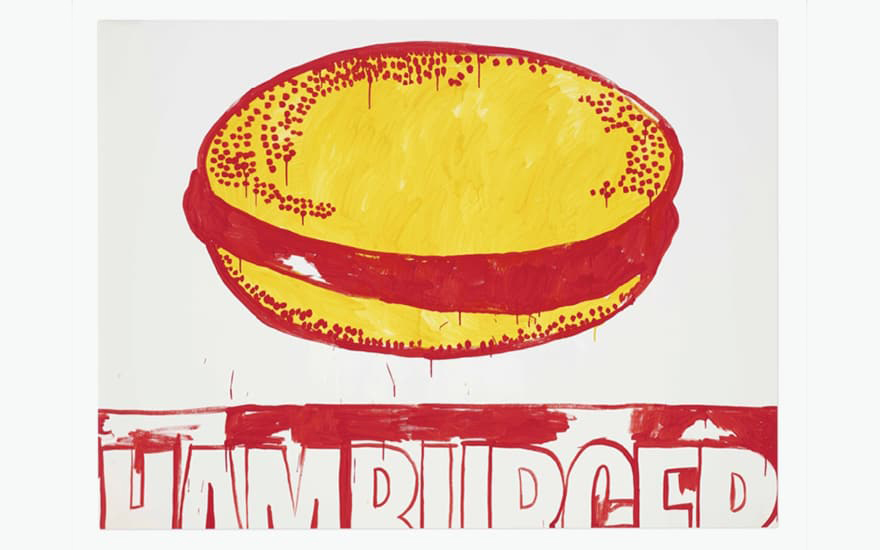

Giant Hamburger, later retitled Floor Burger, was made in 1962, neck and neck with Warhol’s Tomato Soup during the earliest years of pop art’s birth. It was an ugly, lumpy creation, one of many “soft sculptures” the artist had made by stuffing canvas or burlap with chicken wire, newspaper and other refuse. While not a particularly beautiful piece, its goofy presence that demanded so much gallery space was unforgettable and it soon became a visitor favourite and a Toronto landmark.

Oldenburg’s hamburger homage captured something of the epic and the absurd in gastronomy and economy. The hamburger- really, when it comes down to it, nothing more than a hunk of meat between two more hunks of bread- had a fascinating journey from its humble beginnings to the big time, as the world’s most popular sandwich.

Floor Burger, by Claes Oldenburg, 1962

Perhaps even more importantly was all that it symbolized- convenience, entrepreneurial innovation, freedom for women from barefoot kitchen labour, and mega-flavour. The American dream between two buns.

Whether or not some of that has been smothered in fast food’s contribution to the environmental decimation, to the cultural erasure from globalization’s homogenizing impact, and to the diabetes epidemic and world obesity, everyone loves a hamburger. Specific and reliable stats are impossible to come by, but it’s something like 50 billion burgers sold annually- in the USA alone. It’s safe to say world consumption is at least three times that. Other countries adore hamburgers just as much, and choose them whenever given the option- not just Canada, Australia, and the UK, but Spain, China, South Korea, Turkey, Malaysia, Mexico, Japan, Brazil, and beyond.

What is a hamburger? At its most basic definition, it is a sandwich consisting of a ground beef patty wedged between two slices of bread. It is usually served with condiments that can range from blue cheese and truffle goo to bacon and BBQ sauce, but at its most classic, contains ketchup, mustard, lettuce, tomato, onion, and pickles.

Ewan Munro from London, UK, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

There are numerous claims to the invention of the hamburger, but like most origin stories, a seed of truth in each of them works towards forming the bigger picture. The hamburger is a tale of converging events and evolution rather than a singular bingo moment. We can best understand the hamburger as a hybrid of Hamburg, Germany’s genius and American carnival cuisine merging into the spectacular sandwich symbol we know and love today. It is a recipe of ingredients, inventions, history, and business coming together between the buns that makes the hamburger what it is.

“Hamburgh sausage” was first mentioned in Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery Made Easy, 1758 edition out of England. This was basically minced beef in a sausage on toast. The “frikadelle” were, from the 1600s on, popular German meatballs- or possibly Danish meatballs- flattened into a patty. They evolved onto a bun and were called Hamburg Rundstück warm- round Hamburg beef on a warm bun.

Some version of this Hamburg-style steak between bread finds early mentions rather widely from the 1840s onward, between Germany and America. Portable beefsteaks were easy edibles for dock workers and other labourers in both places, widespread port foods, including the Hamburg port in New York.

From the 1890s, there are numerous ads for “hamburger steak sandwiches” in newspapers from Boston to Hawaii. Fast food was being born, with sandwiches appearing for purchase on trains and at business travel hubs, including fairs and carnivals. By 1904, hamburgers at the St. Louis World Fair made the headlines at the New York Tribune as “the innovation of a food vendor on the pike.” Fletcher and Ciddy Davis of Texas were one couple lauded for the pivotal burger with “Old Dave’s Hamburger Stand.” The couple had been selling patty sandwiches in Texas since the 1880s, served with onion slices and a pickle on the side.

However, Charlie Nagreen, nicknamed “Hamburger Charlie” had been selling “Hamburger steak” smashed on a sandwich at another fair, the Seymour Fair in Wisconsin, since 1885. Charlies was a fifteen year old entrepreneur when he had the idea to make meatballs portable to browsers walking through the fair, and sold them there every year until his death in 1951. But there was a parallel contender in the same year, 1885, at the Erie County Fair- in Hamburg, New York. Devotees of the Frank and Charles Menches origin story claim the word “Hamburger” comes from Hamburg, New York, not Germany. However, Tulsa, Oklahoma insists it is “The Real Birthplace of the Hamburger” but “Grandpa Oscar” didn’t serve his first burger until 1891.

WIMHARTER, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Whoever wrote the hamburger story first, it was dependent on a few factors. One was the idea of the sandwich itself, which is even older and more convoluted. The sandwich is attributed to and named after Britain’s John Montagu, Earl of Sandwich, in the early 1700s. Legend says he hated to take a break from gambling for dinner, and a finger food solution was devised. This is a fun story, but nearly every culture has some kind of “bread as plate” dish, where food is served on top of or in between or cooked right into dough.

Just as integral to the evolution of the hamburger was invention of the meat grinder. While we think of minced meat as cheap and lowly, before the Germans dreamed up the device for grinding up animal flesh, ground beef and other meats took a lot of time to prepare. It was easier to take a chunk of something tough and chewy on the go. The tender hamburger- Hamburg steak- on a more mass scale naturally followed the mid-nineteenth century grinder. Likely that the stuff followed German immigrants and travelling businessmen from Germany to the ports of New York State and into the fairs across America. The timing coincided with the German-American Henry John Heinz manufacturing the delicious, popular red sauce we call ketchup, considered by most the perfect marriage for the meat.

Other factors that came together to blast the hamburger sandwich into fast food on an epic industrial and global scale included commercial freezing capabilities, long haul trucking, and air travel. Early restaurants were fair and carnival stands, followed by rapidly expanding restaurant chains like White Castle, Big Boy, and then, of course, McDonald’s and all of its competitors. The rest is, as they say, hamburger history.

The beef in a bun burgers had become so ubiquitous and legendary that by the time pop art was born, they were one of the symbols of deliciousness, mass production, commercialization and globalization, along with tin can soups and Coca Cola. Although Warhol didn’t paint his version of the hamburger until the ‘80s, Toronto had already secured Oldenburg’s Floor Burger by ’67. This was thirteen years before the legendary local Lick’s was born on Queen East.

In this writer’s opinion, Lick’s was the most spectacular burger Toronto ever offered, if you could stand the goofy sing-song grill and counter staff repertoire that set the chain apart. The business has now morphed into an online slogger of frozen patties, and you’ll have to drive north to Parry Sound for Lick’s last remaining open door.

Andrew Currie (CC BY 2.0)

Not quite as far north is Golden Star, an old-school burger shop that opened in ’64. The baby of Frank Doria, who died in 2014, Golden Star remains an old-school holdout that refuses to succumb to Yonge and Steeles condo zoning. With ancient fake Formica wood tables and dingy orange diner décor, neon yellow overhead menu lettering, and a vintage sign outside from the golden age of diners, they continue to serve the same juicy grilled homeburgers that made them famous, along with requisite sides like onion rings and strawberry milkshakes.

Adventurous foodies might be tempted by another Toronto landmark, Alfie’s, a bona fide dive at Queen and Sherbourne. The sign outside has dubiously proclaimed “best hamburgers in town” for as long as I can remember. This Moss Park drinking hole is not just famous for its burgers – recent murders include a baseball bat beating just outside, but luckily a young man shot in the neck survived his visit. Folks milling outside will supply your every need for crack or someone else’s prescription pills.

The ambiance is memorable, too, with no windows at all. Vaughn Chipman for Vice Magazine famously braved the joint for the burger in 2012 and reported, “Using a plastic grocery bag as a glove, the bartender threw two massive piles of ground beef onto the grill…The burger ended up being delicious.”

Marc Falardeau (CC BY 2.0)