Wine and Art is an ongoing GFR series on the relationship between the two creative endeavours by working artist and author Lorette C. Luzajic.  I didn’t love the Rioja I was working on, so I finally opened the bottle of white that had been chilling for seven months at the back of my fridge. Since Spanish wine is my favourite, I thought it would taste better another time – it was just clearly the wrong fit for the delicate cream of lemon-cilantro bisque I’d been simmering all afternoon. Then those first crisp notes of spring hit my palate, and I felt like I was coming out of a long hibernation. Red wine is all seasons wine, to be sure, sleepy and warm and cozy on long winter nights, and sultry and heady in the dead heat. But white’s more subtle profile has a refreshing, understated kind of poetry. Red is smart and sullen and so compelling that sometimes one can forget their first love. A few sips in and I remembered. One should never have to dust off a Riesling.

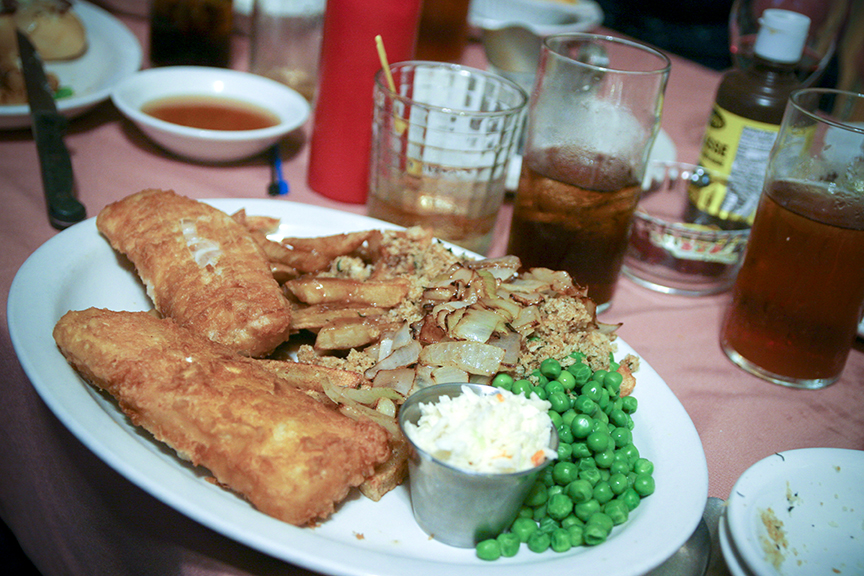

I didn’t love the Rioja I was working on, so I finally opened the bottle of white that had been chilling for seven months at the back of my fridge. Since Spanish wine is my favourite, I thought it would taste better another time – it was just clearly the wrong fit for the delicate cream of lemon-cilantro bisque I’d been simmering all afternoon. Then those first crisp notes of spring hit my palate, and I felt like I was coming out of a long hibernation. Red wine is all seasons wine, to be sure, sleepy and warm and cozy on long winter nights, and sultry and heady in the dead heat. But white’s more subtle profile has a refreshing, understated kind of poetry. Red is smart and sullen and so compelling that sometimes one can forget their first love. A few sips in and I remembered. One should never have to dust off a Riesling.  Germany doesn’t have a sexy reputation in the wine department. We do not picture dinner in Frankfurt the same way that we see the Mediterranean table, an endless parade of olives and citrus and feta and seafood and red, red wine. We’re known as a sturdy people, better stereotyped with a stein of strong craft beer and a sausage than with any kind of cultured, metrosexual flare. I was once told by a store sommelier to skip the German rack altogether in my pursuit of the world’s grapes. And that might be reasonable if one only drinks reds. But those who know that variety is the spice of life know that Germany’s spicy Rieslings are the romance of the rainbow. Riesling’s signature sweet and spicy personality gives it a unique versatility. It can provide the appropriate backseat decorum to menus of lighter fare, like my lemony soup. But it can also stand up to those sausages – Riesling never met a wurst it didn’t like. Even more importantly, this white never waxes washed out or watery. Its fruity and bloom perfume is balanced by an elegant acidity. And there’s that elusive minerality, the much-disputed presence or absence of metallic, chemical nuances, that slate-soaked flavour that tastes like the earth but somehow spartan and clean instead. This quality doesn’t exist in red wine at all, and is too faint in the vast majority of whites. I like to approach wine the way I approach abstract paintings. Each wine has its first impression, its face if you will. In the same way, an abstract artwork evokes an initial response, a summary of its parts reflected in one’s visceral reaction. In both wine and art, there is bound to be a like or dislike right off the bat. This opinion will change as one becomes more deeply acquainted with the work of art, whether it is in the bottle or on canvas. Layers, texture, depth, colour, design- all of the elements are present from the beginning, but it takes time for their full unfolding. We develop a relationship with the work and our experience of it deepens. If we understand more of its context, the biography of the work, its intentions, its methods, its actors, we can develop an appreciation for a wide variety of qualities. Like a Mark Rothko, for example, a liquid work of art can be massive and bold and command a kind of spiritual contemplation. Or it can be more like a Jackson Pollock work, created with rebellious, aggressive strokes and unorthodox techniques. But after its spell wears off, one is left with nothing but a dizzy, ugly mess and an insurmountable bill.

Germany doesn’t have a sexy reputation in the wine department. We do not picture dinner in Frankfurt the same way that we see the Mediterranean table, an endless parade of olives and citrus and feta and seafood and red, red wine. We’re known as a sturdy people, better stereotyped with a stein of strong craft beer and a sausage than with any kind of cultured, metrosexual flare. I was once told by a store sommelier to skip the German rack altogether in my pursuit of the world’s grapes. And that might be reasonable if one only drinks reds. But those who know that variety is the spice of life know that Germany’s spicy Rieslings are the romance of the rainbow. Riesling’s signature sweet and spicy personality gives it a unique versatility. It can provide the appropriate backseat decorum to menus of lighter fare, like my lemony soup. But it can also stand up to those sausages – Riesling never met a wurst it didn’t like. Even more importantly, this white never waxes washed out or watery. Its fruity and bloom perfume is balanced by an elegant acidity. And there’s that elusive minerality, the much-disputed presence or absence of metallic, chemical nuances, that slate-soaked flavour that tastes like the earth but somehow spartan and clean instead. This quality doesn’t exist in red wine at all, and is too faint in the vast majority of whites. I like to approach wine the way I approach abstract paintings. Each wine has its first impression, its face if you will. In the same way, an abstract artwork evokes an initial response, a summary of its parts reflected in one’s visceral reaction. In both wine and art, there is bound to be a like or dislike right off the bat. This opinion will change as one becomes more deeply acquainted with the work of art, whether it is in the bottle or on canvas. Layers, texture, depth, colour, design- all of the elements are present from the beginning, but it takes time for their full unfolding. We develop a relationship with the work and our experience of it deepens. If we understand more of its context, the biography of the work, its intentions, its methods, its actors, we can develop an appreciation for a wide variety of qualities. Like a Mark Rothko, for example, a liquid work of art can be massive and bold and command a kind of spiritual contemplation. Or it can be more like a Jackson Pollock work, created with rebellious, aggressive strokes and unorthodox techniques. But after its spell wears off, one is left with nothing but a dizzy, ugly mess and an insurmountable bill.  I always think of Pinot Grigio as Mondrian – classic, clean, and minimalist. Malbec summons Franz Kline, with its expansive, gestural temperament and uncanny ability to be simultaneously ultramodern and archetypal. And Rioja? The matador machismo of Tempranillo is tempered by a careful craftiness. Such a seduction is best reflected in historical masters like Velazquez and Goya, but if its got to be abstract, Robert Motherwell’s Elegy to the Spanish Republic series could go down nicely enough. Germany’s abstract expressionist export, Hans Hoffman, is a perfect parallel for its Riesling. The wine is seldom white, veering towards the striking greens and yellows that Hoffman favours. The artist’s pragmatic penchant for spatial theory and structure drives his work, and perfectly complements the angular complexity of the wine.

I always think of Pinot Grigio as Mondrian – classic, clean, and minimalist. Malbec summons Franz Kline, with its expansive, gestural temperament and uncanny ability to be simultaneously ultramodern and archetypal. And Rioja? The matador machismo of Tempranillo is tempered by a careful craftiness. Such a seduction is best reflected in historical masters like Velazquez and Goya, but if its got to be abstract, Robert Motherwell’s Elegy to the Spanish Republic series could go down nicely enough. Germany’s abstract expressionist export, Hans Hoffman, is a perfect parallel for its Riesling. The wine is seldom white, veering towards the striking greens and yellows that Hoffman favours. The artist’s pragmatic penchant for spatial theory and structure drives his work, and perfectly complements the angular complexity of the wine.  What I remembered after cleaning out the bottom shelf of my refrigerator is that white wine is no less intoxicating than the brooding intensity of the reds. Unless one is speaking literally, that is. Riesling is famously low in alcohol, which is one of the reasons that it can taste sweet. But what a joy to finish a whole bottle without being overly indulgent. There is nothing I love more than sipping while I work, especially when I can finally pull open the windows and let the springtime into my studio. The heavy-handed effect of the higher percentages can cut creative sessions too short. The muse works best with a lighter touch. There is no happier place that I can be, immersed in both of the best worlds at once, glass in one hand, brush in the other.

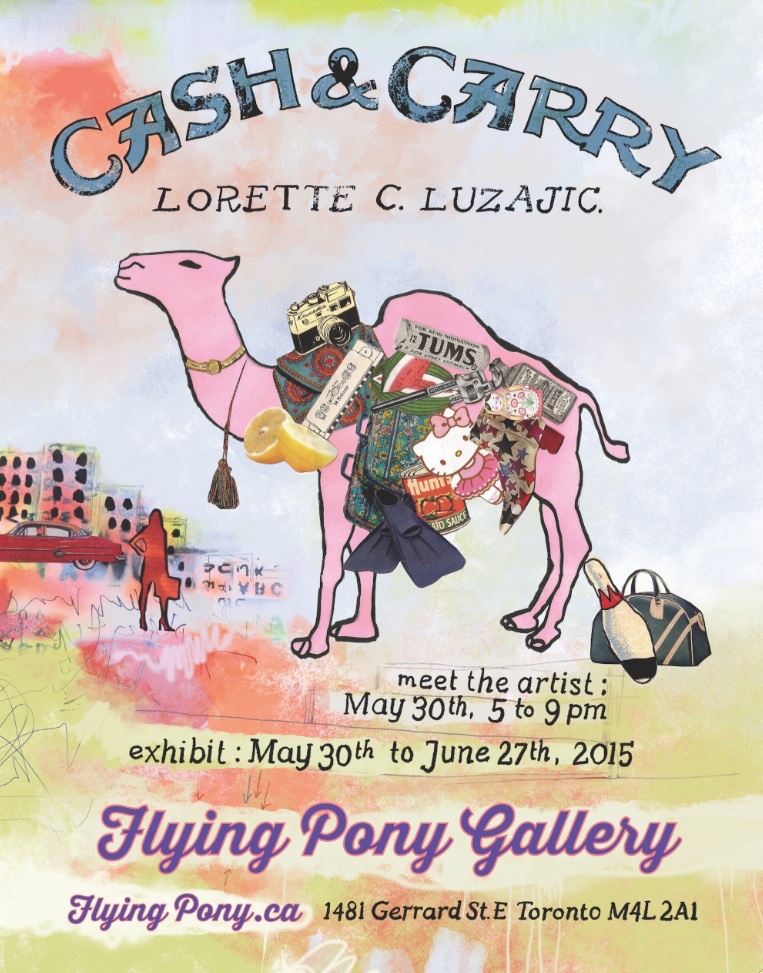

What I remembered after cleaning out the bottom shelf of my refrigerator is that white wine is no less intoxicating than the brooding intensity of the reds. Unless one is speaking literally, that is. Riesling is famously low in alcohol, which is one of the reasons that it can taste sweet. But what a joy to finish a whole bottle without being overly indulgent. There is nothing I love more than sipping while I work, especially when I can finally pull open the windows and let the springtime into my studio. The heavy-handed effect of the higher percentages can cut creative sessions too short. The muse works best with a lighter touch. There is no happier place that I can be, immersed in both of the best worlds at once, glass in one hand, brush in the other.  Join Lorette C. Luzajic at her upcoming solo exhibition, Cash and Carry, at the Flying Pony Gallery on May 30, 5-9 pm, at 1481 Gerrard Street East. The show runs until June 27.

Join Lorette C. Luzajic at her upcoming solo exhibition, Cash and Carry, at the Flying Pony Gallery on May 30, 5-9 pm, at 1481 Gerrard Street East. The show runs until June 27.  Lorette C. Luzajic is an artist and writer with roots in southern Ontario’s wine country soil. Native to Niagara, at home in Toronto, her work is inspired by wine, cheese, and bleak post-apocalyptic literature. Visit her at mixedupmedia.ca. Photo: Ralph Martin.

Lorette C. Luzajic is an artist and writer with roots in southern Ontario’s wine country soil. Native to Niagara, at home in Toronto, her work is inspired by wine, cheese, and bleak post-apocalyptic literature. Visit her at mixedupmedia.ca. Photo: Ralph Martin.

Abstract Pairings

amazingly refreshing blog…can’t wait to go out and get a bottle of Reisling and sip in the spring! Thanks Lorette!