Toronto-based artist Lorette C. Luzajic’s ongoing Good Food Revolution series Wine and Art goes beyond the wine and cheese of an exhibition opening and into the relationship between the arts and wine. Click here to see the whole series.

Toronto-based artist Lorette C. Luzajic’s ongoing Good Food Revolution series Wine and Art goes beyond the wine and cheese of an exhibition opening and into the relationship between the arts and wine. Click here to see the whole series.

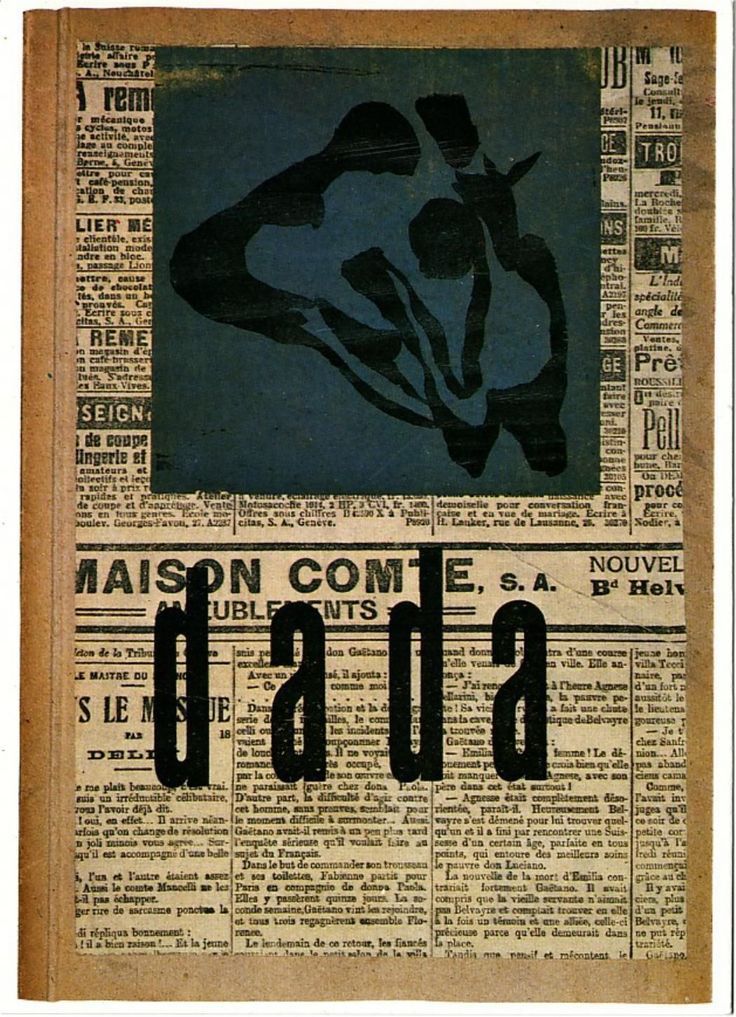

Jean Arp’s prominence in the world of Dada art has always struck me as ridiculous.

As a founding figure of the ism, he was actively philosophizing and making all manner of the absurd, deconstructing and combining disparate elements with no rhyme or reason. This pre-punk epoch grandfathered the culture of the zine, and with the thrill of newly affordable reproductions, cut and paste was given wings. Dada as a movement was preoccupied with nothingness, with meaninglessness, with unbeing, with shock, shlock, and whatever was ugly, rebelling against all tradition in art history.

It didn’t itself yield much oeuvre of lasting importance, but it broke ground by breaking barriers and yielding art to a vast array of important experimentation and revolt that continues to this day.

Dada was the art of anti-art, and this is where I can’t quite place its inventor. Dada as a movement turned its back on beauty, but Arp was never able to evade beauty for long.

I have a big yellow book of Arp’s poetry and other musings, amusing scribblings about Kandinsky and Magritte and Ernst and a whole lot of forced nonsense. It’s laugh out loud wondrous because in all of its missteps of ardent anarchy, I can only see my own reflection in youth. He stumbles from poem to poem with the express purpose of making manure out of gold – “sit down on my big toe”; “piquant suicide”; “the tarred ears of a smoke-giraffe” : “the stone of the universe with the sandwich hair” are some pithy samples. But he couldn’t help but seep beauty from his ink splattered pores, and said things like this, too: “Soon people will speak of silence as they do about about a fairy tale”; “the stars are dying in their aviaries”; and, “toward the infinite white.”

Arp meant to deconstruct whole concepts like purpose and meaning and beauty, and reduce them to their most primitive, elemental essence. But the bold, childish shapes that look like noses glued willy nilly somehow can’t escape their bourgeois confines of pleasing symmetry.

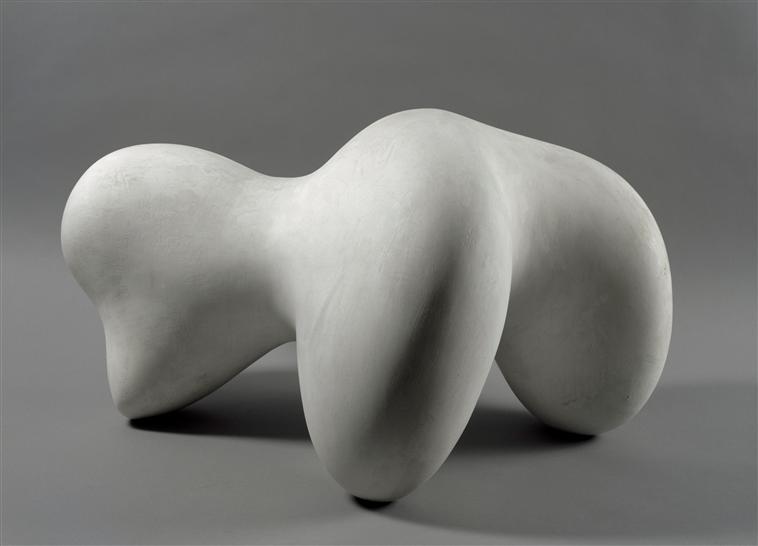

Arp should never have dared to take up sculpture. Every stone he touched turned sublime.

Perhaps his sculptures were an act of submission. Ultimately, we are powerless to resist the impact beauty has on our soul.

His sculptures were most carnal; they were bold, smooth, sensuous acts of minimalism. But the spare and simple and heavy works were never clinical or sterile. His art was fertile, voluptuous, tender.

Jean Arp made boulders weightless, sensual, as soft and luminous as Marilyn Monroe.

Jean Arp made boulders weightless, sensual, as soft and luminous as Marilyn Monroe.

Pairing wine and Arp is admittedly a bit of a stretch: if this artist had a passion for the fruits of the vine, it’s not something he’s famous for. Yet I can’t help but summon his 3-D whenever wine talk turns to body and structure. I often think of the weight of wine as sculpture. All of the properties of wine, from its perfume bouquet to its sensual, sedating effects, to the aesthetics of colour, ultimately rest on its body.

“What does ‘wine structure’ even mean?” asks Courtney Schiessl, a Brooklyn-based sommelier and wine writer. She writes at the wine website vinepair.com, “Structure essentially refers to the major elements that can be assessed when tasting a wine: acidity, sweetness, body, alcohol, and tannin.”

Be that as it may, wine’s structure is not about an esoteric wagging of aficionado tongues- it is everything solid and tangible about our experience of wine. Even without the right words, we can tell during pouring whether a wine is thin and translucent, or sturdy and opaque. You might think here of the texture differences between skim milk and cream.

The way wine sits in our mouth is separate from its flavours. Some wines we instinctively describe as light and airy, and others are thick and solid. And while it wouldn’t hold up in a court of foodie law, I personally consider the effects of the wine to be part of its sculpture. Some pale pinks have a frilly, gauzy kind of mellowing, flitting about us like fireflies. Other highs are more ornate, with a tangle of moody limbs outstretched in pleasing curvature and lots of flickering bits of metallic. Bernini, perhaps, or all the other fountains of Rome. At times, the intoxication’s structure is reliable and solid, like carpentry and blueprints for a back deck.

I spend a lot of time and writing extolling the virtues of wine, its poetry and spirituality and sensuousness and history and connection to the past and to other worlds away. But wine is also earthy and essential; it is something we consume as food. This is just as much sculpture as remixing stones and paper cutouts into two or three dimensions.

I spend a lot of time and writing extolling the virtues of wine, its poetry and spirituality and sensuousness and history and connection to the past and to other worlds away. But wine is also earthy and essential; it is something we consume as food. This is just as much sculpture as remixing stones and paper cutouts into two or three dimensions.

I don’t know why it is for me that contemplation of Arp’s art always makes me thirsty. His fight against what is beautiful ironically led him full circle, back to beauty, making his struggle to depart from traditional aesthetics as absurd as his intentions. While I could readily get matchy matchy and pin a post-it note declaration of “shiraz” or “Garganega” on various examples of his sculpture, I want to suggest instead a different kind of game: might we ask ourselves how mystery and mythology and beauty intersect with the ingredients in our life that are concrete and corporeal?

On those occasions where we try to reconcile our emblems of science to the palpable and real, might we consider that our very attempts at reductionism only reveal beauty for what it is?

Wine and art are among the few eternal elements in the human story, with us from the start: I suspect they will outlast and outshine all of us, and all of our attempts to explain them.

See more of Lorette C. Luzajic at mixedupmedia.ca.