I will begin this article by admitting that I may have been biased. Each year that I attended the Northwest Wine Expedition, an annual gathering of producers from all over Oregon and Washington, my deep love for Oregon and its lithe Pinot Noirs and Chardonnays always drew me to focus heavily on their presence. In fact, in previous coverages of these events (you can read those here and here), I was generally unimpressed with the limited number of Cabernet Sauvignon wines I tasted, and my opinions on such styles are evidently transparent.

This year, I was determined to give things another chance, and I’ve always said that if you hate (hate is a strong word – Ed.) something, you better really know why; I once listened through an entire Justin Bieber album to justify my disdain.

Fellow GFR writer Olivia Siu and I split the event in half (check out her rundown here), and I chose Washington.

There’s never enough space in the article to thoroughly speak about both while actually saying something worth reading, and I personally wanted to see if there was something I’d been missing. There was. With ancient ice age floods, a growing history hundreds of years old, and some of the most diverse soil profiles anywhere in the world, Washington captured my interest and maybe a bit of my heart.

It feels like Washington’s winemakers can make just about anything they like, though with all of Washington’s versatility, a style still seems to be emerging, almost subconsciously.

Perhaps there is a growing desire to distance their wines from the reputation of Napa Valley and its relatives as a region where Cabernet Sauvignon predominates.

This year’s wines were generally more acidic, mineral, savoury, and made with well-integrated oak and true varietal character. Even in one of Washington’s hottest and driest AVA’s, this still rings true. The arid Red Mountain AVA was out in force at the Northwest Wine Expedition this year. In fact, I had really set out to taste wines from the Columbia Gorge and Walla Walla, areas that blur the line between Washington and Oregon’s terroirs, but things don’t always go to plan, and I instead pursued the mountain’s fascinating history and visceral style.

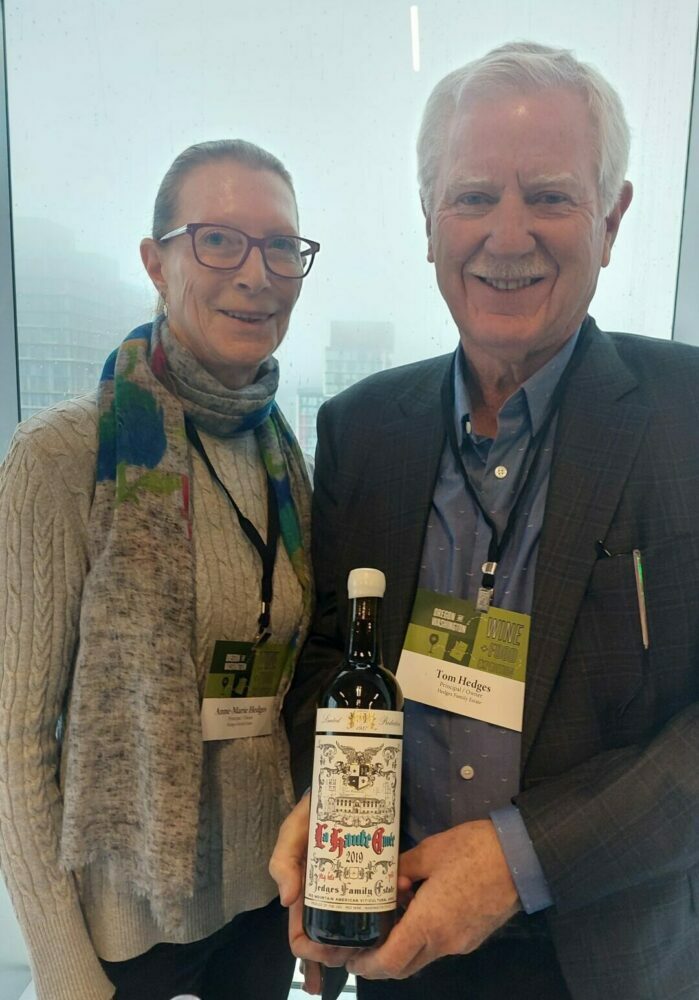

Tom and Anne-Marie Hedges posing with their prized Haute Cuvee release

As always, I’m most interested in speaking directly to a winemaker tending their own table, and Tom and Anne-Marie Hedges caught my eye this year. A family owned and operated Estate, established in 1987 at the heart of Red Mountain AVA, they tend a full Organic and biodynamically certified 130 acres of planted land.

The wines I tasted were balanced, textured, with excellent acidity and tension, and deeply rooted in the old-world. There are a lot of boxes being checked here, and their new certifications speak for a lot of the movement occurring within Washington right now.

Low rainfall, coupled with near-desert conditions and mountain winds, means the conversion to more natural vineyard management and winemaking techniques comes rather naturally (pun unintended). Hedges vineyards sit on the floor and low slopes of the mountain, where many of the first plantings were laid in 1975 on the sediment left behind by the great Missoula Floods. There, they’ve planted several Rhone and Bordeaux varieties, producing both varietal and blended wines.

The 2020 Hedges Estate red drinks like Bordeaux and Northern Rhône formed a supergroup, a smash of the deep structure and savouriness of the mountains with the deep fruit and oak of Bordeaux. Menthol, ripe red currants, and black cherries, a wonderful integration of classic baking spices, finish distinctly ferrous and bloody. Split 55% Cabernet Sauvignon, 26% Merlot, 9% Syrah, 6% Cabernet Franc 3% Malbec, and 1% Petit Verdot, this is a well balanced but still powerful offering, with toothy tannins and great acid to boot. $41.25 on clearance at the LCBO right now with a couple dozen bottles remaining, snag ‘er up!

![]()

This wine represents the history and classic style that dominate most of the Red Mountain AVA, but a change is slowly and surely occurring. Producers are seeking higher, steeper, and ever more extreme terriors. Red Mountain’s peak reaches over 1,400 ft of elevation, and each year plantings creep closer.

In fact, what we’re seeing in Red Mountain is just a small part of the overall larger movement. The true volcanic, basalt soils of Washington are high up, where ancient flood waters failed to drown the mountain tops and lay the sediment that provides the basis for the Columbia Valley. These vineyards, such as the newly anointed Candy Mountain AVA, reach heights of 1,360ft above sea level.

Further east, by the Walla Walla River, steeply sloped rocky hills brimming with exposed basalt sit yet unplanted and untested, assuredly not for long. As producers venture higher, aspects are changing as well. Many vineyards are being planted on north facing slopes instead of traditional south facing slopes, changing the nature of sun and wind exposure and yielding fresher styles with livelier acid.

These sites are a gamble now, but they may reap incredible benefits down the road. Climate change will come for us all, and even Washington, which currently sits in a window of remarkable climatic stability, will eventually feel the brunt of that change. Winemakers are future-proofing their region while meeting the changing demands of consumers. It’s no secret that a collective palate fatigue has set in for the ultra-rich, ultra-extracted oak monster Cab’s of the last two decades, and Washington now sits perfectly positioned to absorb this new interest into their reputation.

We cannot, however, talk about the trends of the market without looking at some new exemplars of Washington’s versatility. SMAK produces exclusively rosé style wines with grapes from single vineyards all over the valley.

After a full day of Cabernet Sauvignon’s and Syrah’s all vying for the title of “most age-worthy and concentrated”, I was overjoyed to see the table of bright, pale rosé wines. Fiona S. Mak, winemaker and founder, produces single-vineyard rosé’s in the Walla Walla Valley, each wine made for a different season of the year.

I have a soft spot for well made rosé’s, and this level of commitment to them tugs my heartstrings, I admit. These were some of the only rosé wines on offer at NWWE, and I find it important to represent the diversity in style that Washington is capable of.

Her 2021 Spring rosé, a 100% Sangiovese wine hailing from the Mission Hill Vineyard, is a fully dry, gently skin-contacted rosé flush with florality and sweet citrus oils. A sapid and refreshing palate laced with wet stone and juicy acidity drives it all home.

![]()

Rosémaker Fiona Mak. (I realize I made everyone do the same pose, but to be fair it is a good pose.)

Finally, some honourable mentions from the event:

2018 Betz Single Vineyard Syrah, “La Serenne”, returned. I noticed a marked improvement that validates what I said about it last year, showing more depth of fruit and plusher tannins.

![]()

2019 Valdemar Cabernet Sauvignon from the Walla Walla was bursting with garrigue, earth and dark layered fruit. Tons of weight and quality tannin, brings me back to the old Bordeaux adage of “the iron fist in the velvet glove”. This is big wine for big bucks.

![]()

With the combination of exciting new terroirs, excellent value, and dark(er) horse varieties like Malbec and Sangiovese showing incredible promise (not to mention some incredible Syrah, which I swooned over last year), it’s hard not to feel Washington’s momentum. Everything they need to become one of the great wine producing regions of the world is there; all it will take is time and a few ambitious (and maybe slightly insane) winemakers.

There is a lot of solace in that promise of progress in a sector where there is so much uncertainty.

(All wines are rated out of a possible five apples)