Wine and Art is an ongoing GFR series on the relationship between the two creative endeavours by working artist and author Lorette C. Luzajic.  I can’t imagine that 17th century Dutch wine was all that good, but Johannes Vermeer is a magician. He is able to tempt us to the table with his painting, Glass of Wine (pictured above), transporting us four centuries into the past. In his familiar room with the dark and light diamond floor, we watch a young woman’s exquisite hesitation before she sips forbidden potion. True, the boyfriend’s there, his hand clasped on the jug, ready to fill ‘er up. He needn’t be so obvious, or impatient. But we understand why he’s so enamoured by the little lady who demurely courts her glass. The sunbeams breaking the heavy dark of these Dutch interior paintings glow on her scarlet gown. This painting is incredibly sensual, reveling in a gentle yet insistent Eros, and some delicious mystery. And so it is a wholly unsuccessful painting. It is supposed to be a warning, not an invitation, to the evils of wine and other vice. But as they say, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. This is as good a cue as any to select a libation as a contemplative aid. Since Dutch wine is hard to find in Toronto, I went with neighbouring Germany. This was a chance for me to branch out, so I took it. Germany has been producing wine since ancient Roman times – at least 1700 years – but it’s not usually my first pick. And not usually anyone’s else’s. Sure, for those who like their wines sweet and spicy, Germany can boast of some very fine Riesling and Gewürztraminer wines. But the nation is best known, if you’ll pardon the pun, for wines at the bottom of the barrel. Some historians blame the Protestant Reformation for the region’s un-sexy wine reputation. The Judeo-Christian tradition celebrated moderate, joyful use of spirits until this time, when killjoys like Martin Luther and John Calvin decided God’s gifts were actually poisons from the devil. Until then, wine was always central even to Christianity’s most sacred ritual, the Eucharist, where it represented life itself. But in the 1500s and onwards, the traditions of monks responsible for much of Europe’s wine history were obliterated and forgotten during the sweep of the Reformation. Areas like Spain, Italy, and France that remained predominantly Catholic have, of course, the best wines in the world, an unbroken lineage across millennium. The flaw in this story is invisible until you find yourself with a stein of spectacular German beer. Beer was around these parts of Europe for about a thousand years longer than wine. But beer was equally a target during the vice squad crackdowns that swept the continent from the 1500s on. So we are left with holes in the theory, and holes burned in sour guts by the likes of Blue Nun and Black Tower. Some scientists suggest the climate is simply not as hospitable as others to amazing grapes. Whether or not Protestants are to blame for the mediocre wines in Germany and the surrounding Low Countries, we can definitely say that Vermeer and the Dutch interior genre of painting was the consolation prize of the Reformation. Art had always been grand in themes and execution, with subjects of religious and classical mythology. But now all religious art was considered idolatry, so painting began to shift to mundane themes of everyday life instead. Enter all the bowls of fruit or flowers, the pastorals and landscapes, and the people sitting around reading. Art also began to reflect the pictorial admonishment of vice. Works of art were now meant to use non-religious figures- ordinary people- to act as warnings about the wages of sin. All this explains why in the 1500s and 1600s so many paintings of peasants playing cards, passing out with their pants down, start showing up in museums the world over. Vermeer was Dutch Reformed, but he converted to Catholicism to marry his fiancee. We can’t know much at all about the motivations or ideas of Johannes Vermeer, because very little remains in evidence of his life. But I like to speculate that this enmeshment of spiritual philosophies is why Vermeer does a lousy job of warning us off of the pleasures that lead us astray. On the surface, his genre paintings look like those of his colleagues, with all the requisite lutes and pitchers and tablecloths. But his works cling stubbornly to a sublime ideal of beauty, outmoded under the new Puritanism. The folks in his artwork retain mythical, ethereal qualities rather than looking down to earth. He imbues even the quotidian toil of tasks with more spirituality and lofty enchantment than their due.

I can’t imagine that 17th century Dutch wine was all that good, but Johannes Vermeer is a magician. He is able to tempt us to the table with his painting, Glass of Wine (pictured above), transporting us four centuries into the past. In his familiar room with the dark and light diamond floor, we watch a young woman’s exquisite hesitation before she sips forbidden potion. True, the boyfriend’s there, his hand clasped on the jug, ready to fill ‘er up. He needn’t be so obvious, or impatient. But we understand why he’s so enamoured by the little lady who demurely courts her glass. The sunbeams breaking the heavy dark of these Dutch interior paintings glow on her scarlet gown. This painting is incredibly sensual, reveling in a gentle yet insistent Eros, and some delicious mystery. And so it is a wholly unsuccessful painting. It is supposed to be a warning, not an invitation, to the evils of wine and other vice. But as they say, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. This is as good a cue as any to select a libation as a contemplative aid. Since Dutch wine is hard to find in Toronto, I went with neighbouring Germany. This was a chance for me to branch out, so I took it. Germany has been producing wine since ancient Roman times – at least 1700 years – but it’s not usually my first pick. And not usually anyone’s else’s. Sure, for those who like their wines sweet and spicy, Germany can boast of some very fine Riesling and Gewürztraminer wines. But the nation is best known, if you’ll pardon the pun, for wines at the bottom of the barrel. Some historians blame the Protestant Reformation for the region’s un-sexy wine reputation. The Judeo-Christian tradition celebrated moderate, joyful use of spirits until this time, when killjoys like Martin Luther and John Calvin decided God’s gifts were actually poisons from the devil. Until then, wine was always central even to Christianity’s most sacred ritual, the Eucharist, where it represented life itself. But in the 1500s and onwards, the traditions of monks responsible for much of Europe’s wine history were obliterated and forgotten during the sweep of the Reformation. Areas like Spain, Italy, and France that remained predominantly Catholic have, of course, the best wines in the world, an unbroken lineage across millennium. The flaw in this story is invisible until you find yourself with a stein of spectacular German beer. Beer was around these parts of Europe for about a thousand years longer than wine. But beer was equally a target during the vice squad crackdowns that swept the continent from the 1500s on. So we are left with holes in the theory, and holes burned in sour guts by the likes of Blue Nun and Black Tower. Some scientists suggest the climate is simply not as hospitable as others to amazing grapes. Whether or not Protestants are to blame for the mediocre wines in Germany and the surrounding Low Countries, we can definitely say that Vermeer and the Dutch interior genre of painting was the consolation prize of the Reformation. Art had always been grand in themes and execution, with subjects of religious and classical mythology. But now all religious art was considered idolatry, so painting began to shift to mundane themes of everyday life instead. Enter all the bowls of fruit or flowers, the pastorals and landscapes, and the people sitting around reading. Art also began to reflect the pictorial admonishment of vice. Works of art were now meant to use non-religious figures- ordinary people- to act as warnings about the wages of sin. All this explains why in the 1500s and 1600s so many paintings of peasants playing cards, passing out with their pants down, start showing up in museums the world over. Vermeer was Dutch Reformed, but he converted to Catholicism to marry his fiancee. We can’t know much at all about the motivations or ideas of Johannes Vermeer, because very little remains in evidence of his life. But I like to speculate that this enmeshment of spiritual philosophies is why Vermeer does a lousy job of warning us off of the pleasures that lead us astray. On the surface, his genre paintings look like those of his colleagues, with all the requisite lutes and pitchers and tablecloths. But his works cling stubbornly to a sublime ideal of beauty, outmoded under the new Puritanism. The folks in his artwork retain mythical, ethereal qualities rather than looking down to earth. He imbues even the quotidian toil of tasks with more spirituality and lofty enchantment than their due.  Vermeer’s peers do not have the same sensual touch. Gerard Ter Borch uses the same props as Vermeer – the lutes, the funny pantaloons, the little dog. His works most probably were influential to Vermeer. And he too can’t quite let go of beauty, which after all, drives an artist. But he does not have Vermeer’s airy, idealist fingers. He is much more blatant in his admonishments against drink. In his work, the woman holds her own jug. In that one, her companion has already passed out.

Vermeer’s peers do not have the same sensual touch. Gerard Ter Borch uses the same props as Vermeer – the lutes, the funny pantaloons, the little dog. His works most probably were influential to Vermeer. And he too can’t quite let go of beauty, which after all, drives an artist. But he does not have Vermeer’s airy, idealist fingers. He is much more blatant in his admonishments against drink. In his work, the woman holds her own jug. In that one, her companion has already passed out.  In another, a half-soused maiden is clinging to the arm of a lecherous date, playing at keeping the glass away while giving full permission for a refill with her eyes.

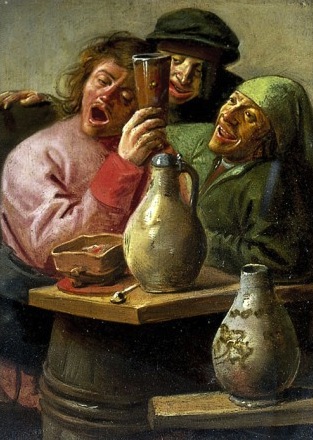

In another, a half-soused maiden is clinging to the arm of a lecherous date, playing at keeping the glass away while giving full permission for a refill with her eyes.  Jan Steen went out of his way to show humans at their most base, with boisterous groups of ugly villagers, drinking, gambling, and dancing in chaotic heaps of disarray. He was really a Catholic but took great joy in creating in the new Reformed style.

Jan Steen went out of his way to show humans at their most base, with boisterous groups of ugly villagers, drinking, gambling, and dancing in chaotic heaps of disarray. He was really a Catholic but took great joy in creating in the new Reformed style.  Adriaen Brouwer made no apology of his focus on slovenly details, with ruddy men and unbathed women. At times one almost wonders if his work is satire rather than conviction- but one need only picture the realistic state of history and humanity at this time to think it was realism of an important sort. In any event, the kinds of art being produced reflected the kinds of art permitted. Protestant paintings meant protest paintings. You could protest gluttony and avarice and boozing. You could draw some boring pears. But the rest was vanity. Or worse, idolatry. The iconoclasts of the era rampaged through cathedrals and convents, urinating on crucifixes and building bonfires on which they burned priceless sculptures and paintings. They dictated what could be created from then on. The Catholic Church had been the most important patron and inspiration of art, and depictions of classical mythology and Christian theology were mainstays of art history. To Protestants, these were emblems of ostentatious excess. They hated empty pomp and ceremony as distractions from focus on God, and saw ecclesiastic extravagance as being at the expense of the common man. These things were all worthy of examination. But unfortunately, these condemnations included the belief that pleasure and beauty – wine and art, for example, were idolatry. Reformers interpreted the practice of contemplation of religious art as worship of objects.

Adriaen Brouwer made no apology of his focus on slovenly details, with ruddy men and unbathed women. At times one almost wonders if his work is satire rather than conviction- but one need only picture the realistic state of history and humanity at this time to think it was realism of an important sort. In any event, the kinds of art being produced reflected the kinds of art permitted. Protestant paintings meant protest paintings. You could protest gluttony and avarice and boozing. You could draw some boring pears. But the rest was vanity. Or worse, idolatry. The iconoclasts of the era rampaged through cathedrals and convents, urinating on crucifixes and building bonfires on which they burned priceless sculptures and paintings. They dictated what could be created from then on. The Catholic Church had been the most important patron and inspiration of art, and depictions of classical mythology and Christian theology were mainstays of art history. To Protestants, these were emblems of ostentatious excess. They hated empty pomp and ceremony as distractions from focus on God, and saw ecclesiastic extravagance as being at the expense of the common man. These things were all worthy of examination. But unfortunately, these condemnations included the belief that pleasure and beauty – wine and art, for example, were idolatry. Reformers interpreted the practice of contemplation of religious art as worship of objects.  The no-frills approach to spirituality had much to recommend it. The Protestants put the Bible into the hands of the people, for example, whereas historically it was only allowed in the hands of the clergy. This contributed hugely to spreading literacy near and far. It had always been only for the elite. The demands of the Protestants also helped to limit the darker powers of the church, such as the con men selling tickets to heaven in the form of indulgences. Poor, ignorant, desperate and sick people who could least afford them were conned out of their meager pennies on such empty promises. But in place of beauty and art, Protestants had their own idols of austerity and severity. The impassioned punishment of Catholics gave way to the asceticism of Puritanism. From our future vantage point of four hundred years, we can bargain with John Calvin to declare that dancing and wine and other evil spirits and art are not valid reasons to be sent to the gallows. We can duke it out with John Wesley, who said, “You see the wine when it sparkles in the cup, and are going to drink of it. I tell you there is poison in it! and, therefore, beg you to throw it away.” We can point to the parts of the Bible that they missed, such as the erotic love poetry of Solomon, which was full of wine and kissing. And all that lyre playing and the dancing in the Psalms. And the part where Christ himself was caught red handed, not just drinking wine, but making it. And those of us who passionately hold the belief that creativity is a divine attribute – the part of us “made in the image of God”- can rage against the sheer folly of Calvin and Co.’s rejection of music and art and theatre. But this grievous fallacy propelled art history in unexpected directions. One was the ultimate secularization of art. All those paintings of dusty wine glasses and apples and other routine objects changed the monopoly of meaning for art and opened the playing field to all subjects and all people. Another effect was a radical shift in the patronization of art, and in the art market.

The no-frills approach to spirituality had much to recommend it. The Protestants put the Bible into the hands of the people, for example, whereas historically it was only allowed in the hands of the clergy. This contributed hugely to spreading literacy near and far. It had always been only for the elite. The demands of the Protestants also helped to limit the darker powers of the church, such as the con men selling tickets to heaven in the form of indulgences. Poor, ignorant, desperate and sick people who could least afford them were conned out of their meager pennies on such empty promises. But in place of beauty and art, Protestants had their own idols of austerity and severity. The impassioned punishment of Catholics gave way to the asceticism of Puritanism. From our future vantage point of four hundred years, we can bargain with John Calvin to declare that dancing and wine and other evil spirits and art are not valid reasons to be sent to the gallows. We can duke it out with John Wesley, who said, “You see the wine when it sparkles in the cup, and are going to drink of it. I tell you there is poison in it! and, therefore, beg you to throw it away.” We can point to the parts of the Bible that they missed, such as the erotic love poetry of Solomon, which was full of wine and kissing. And all that lyre playing and the dancing in the Psalms. And the part where Christ himself was caught red handed, not just drinking wine, but making it. And those of us who passionately hold the belief that creativity is a divine attribute – the part of us “made in the image of God”- can rage against the sheer folly of Calvin and Co.’s rejection of music and art and theatre. But this grievous fallacy propelled art history in unexpected directions. One was the ultimate secularization of art. All those paintings of dusty wine glasses and apples and other routine objects changed the monopoly of meaning for art and opened the playing field to all subjects and all people. Another effect was a radical shift in the patronization of art, and in the art market.  Dutch genre paintings were filled with regular people, not martyrs and saints. They also showed rooms and objects and food, everyday aesthetics for everyday people. This meant ordinary people saw their own lives in artworks, and that meant the artworks found their way onto their walls. For centuries the Catholic Church had been the money behind art, and the Reformed Church had no art at all. This also changed the market profoundly. Artists began painting smaller works meant for home walls, not cathedrals. Artists now painted with hopes of selling to other kinds of buyers. Without the church to support them, they set their sights on middle class citizens. Changing subject matters brought a changing audience. That meant sudden artistic freedom. They no longer had to paint the dictates of the old church. The new church had dictates, too, but with the fading influence of central spiritual power, and the power of the market in the hands of the people, artists found themselves more and more empowered towards a wider range of expressions.

Dutch genre paintings were filled with regular people, not martyrs and saints. They also showed rooms and objects and food, everyday aesthetics for everyday people. This meant ordinary people saw their own lives in artworks, and that meant the artworks found their way onto their walls. For centuries the Catholic Church had been the money behind art, and the Reformed Church had no art at all. This also changed the market profoundly. Artists began painting smaller works meant for home walls, not cathedrals. Artists now painted with hopes of selling to other kinds of buyers. Without the church to support them, they set their sights on middle class citizens. Changing subject matters brought a changing audience. That meant sudden artistic freedom. They no longer had to paint the dictates of the old church. The new church had dictates, too, but with the fading influence of central spiritual power, and the power of the market in the hands of the people, artists found themselves more and more empowered towards a wider range of expressions.  Buying art was so hot that it stands out in the study of Dutch and Flemish art. Look at how many of the paintings feature paintings. The Wine Glass features a piece of stained glass, coyly toying with the painting’s supposed message of resisting drink by showing Temperance and her glass. Nearly every Vermeer painting shows multiple artworks in the background. The works by his colleagues show the same phenomenon. This is because the private ownership of art had skyrocketed exponentially and now all homes with any means at all had art collections of their own. Indeed, what is now the Netherlands was a major, if not the crown, commercial art hub of the entire world at the time. The Reformation’s hope was to reduce the importance of art but it was turned on its head. Proliferation of painting ownership began to mushroom like wildfire into every parlour and every corner of commerce. Today art is common in homes of all classes. Finally, the Counter-Reformation, or Catholic Reformation, came about in response to the Reformation. While there was some kowtowing to criticisms, the greater effects came when the church “decided to make a virtue of what many regarded as its weaknesses,” as historian Paul Johnson wrote in Art: a New History. The church, “embarked on a deliberate policy of emphasizing the spectacular…churches…were to be ablaze with light, clouded with incense, draped in lace, smothered in gilt, with huge high altars, splendid vestments, sonourous organs, and vast choirs…Catholicism would respond to simplicity and primitive austerity with all the riches and colour and swirling lines and glitter in its repertoire, adding new visual effects as artists could create them.” And so it is that art moved in two distinct directions. One was the plain art for plain people direction, spawned from the revolutionary idea that led to unprecedented commerce of paintings and ultimately all secular and modern art. The other was the glorious, grandiose exaggeration of beauty and ornament. The rebellion against Puritanism ushered in the spectacular lavishness of high Baroque and then Rococo art. These eras of art are flamboyant and dazzling and gaudy jewels in the human idea factory. Needless to say, all the bonfires lit and topped with irreplaceable paintings did not quench the human appetite for beauty. And no matter how many times Dutch tavern scenarios warned us of the ravages of the demon grape, wine has never been as perfected an art, or as popular, as it is today. There were many positive changes to history, of course, wrought by the Reformation- this being one of them. The objective to crush the importance of art turned out the exact opposite. As the saying goes, the Lord works in mysterious ways. Cheers!

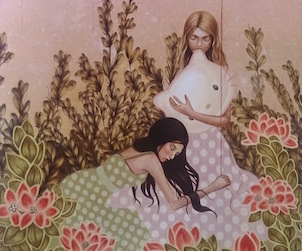

Buying art was so hot that it stands out in the study of Dutch and Flemish art. Look at how many of the paintings feature paintings. The Wine Glass features a piece of stained glass, coyly toying with the painting’s supposed message of resisting drink by showing Temperance and her glass. Nearly every Vermeer painting shows multiple artworks in the background. The works by his colleagues show the same phenomenon. This is because the private ownership of art had skyrocketed exponentially and now all homes with any means at all had art collections of their own. Indeed, what is now the Netherlands was a major, if not the crown, commercial art hub of the entire world at the time. The Reformation’s hope was to reduce the importance of art but it was turned on its head. Proliferation of painting ownership began to mushroom like wildfire into every parlour and every corner of commerce. Today art is common in homes of all classes. Finally, the Counter-Reformation, or Catholic Reformation, came about in response to the Reformation. While there was some kowtowing to criticisms, the greater effects came when the church “decided to make a virtue of what many regarded as its weaknesses,” as historian Paul Johnson wrote in Art: a New History. The church, “embarked on a deliberate policy of emphasizing the spectacular…churches…were to be ablaze with light, clouded with incense, draped in lace, smothered in gilt, with huge high altars, splendid vestments, sonourous organs, and vast choirs…Catholicism would respond to simplicity and primitive austerity with all the riches and colour and swirling lines and glitter in its repertoire, adding new visual effects as artists could create them.” And so it is that art moved in two distinct directions. One was the plain art for plain people direction, spawned from the revolutionary idea that led to unprecedented commerce of paintings and ultimately all secular and modern art. The other was the glorious, grandiose exaggeration of beauty and ornament. The rebellion against Puritanism ushered in the spectacular lavishness of high Baroque and then Rococo art. These eras of art are flamboyant and dazzling and gaudy jewels in the human idea factory. Needless to say, all the bonfires lit and topped with irreplaceable paintings did not quench the human appetite for beauty. And no matter how many times Dutch tavern scenarios warned us of the ravages of the demon grape, wine has never been as perfected an art, or as popular, as it is today. There were many positive changes to history, of course, wrought by the Reformation- this being one of them. The objective to crush the importance of art turned out the exact opposite. As the saying goes, the Lord works in mysterious ways. Cheers!  Lorette C. Luzajic is an artist and writer with roots in southern Ontario’s wine country soil. Native to Niagara, at home in Toronto, her work is inspired by wine, cheese, and bleak post-apocalyptic literature. If you missed her at the ROM or the Ritz, visit her at mixedupmedia.ca. Photo: Ralph Martin.

Lorette C. Luzajic is an artist and writer with roots in southern Ontario’s wine country soil. Native to Niagara, at home in Toronto, her work is inspired by wine, cheese, and bleak post-apocalyptic literature. If you missed her at the ROM or the Ritz, visit her at mixedupmedia.ca. Photo: Ralph Martin.

Wijn Reformatie

I was just at the Rijksmuseum and noticed a lot of “partying” in the paintings. Thanks for this! Very interesting.

Your writing has taken me to places in art that I would never with my own eyes. I love the way you write. Dad enjoyed this one to! Love you and thank you again! Your #1 and 2 fans!