When I arrived on that crisp October day, I felt confident and comfortable about the event ahead.

It was my first time at Kampai Toronto, the largest sake festival in Canada, but I had been to large tastings like this before, and I knew the score. Where to look, who to talk to, what kind of questions to ask, and pretty much all of that went out out the window.

I was out of my element, overwhelmed, flummoxed, and absolutely, completely, having the time of my life.

I learned very quickly that the logic of my wine-brain could not be applied here. Sake is an island unto itself, much like the country it hails from. It is insular, proud, deeply rooted in tradition, and completely unique.

The event hall, soon to be full of eager sake drinkers

I did what I always do at wine events, and that’s focus on a singular style and expression to sniff out (pun intended) the subtleties between regions and brewers.

I decided to try as much Junmai sake as possible.

Sake is divided into several grades depending on how the rice is milled, and if brewers alcohol is allowed in the final product. Junmai sakes are pure rice sakes, with no added alcohol, though Junmais are not always the highest quality sake, some added brewers alcohol is not always a bad thing and in a lot of cases can enhance the body and aromatics of the sake. Junmai is simply what I am most familiar with, and it’s what you’ll find dotting LCBO shelves.

The real high-quality indicators are Ginjo and Daiginjo, referring to how finely the rice has been milled, the latter being the finest and usually considered the pinnacle of a brewers craft. Of course, sake is home to a wide variety of styles and regions, and the masterclass with esteemed Ontario sake Sommelier Michael Tremblay was barely able to scrape the surface. There are sakes infused with citrus and botanicals, styles ranging from dry to sweet, and countless different types of rice, and even made in sparkling styles.

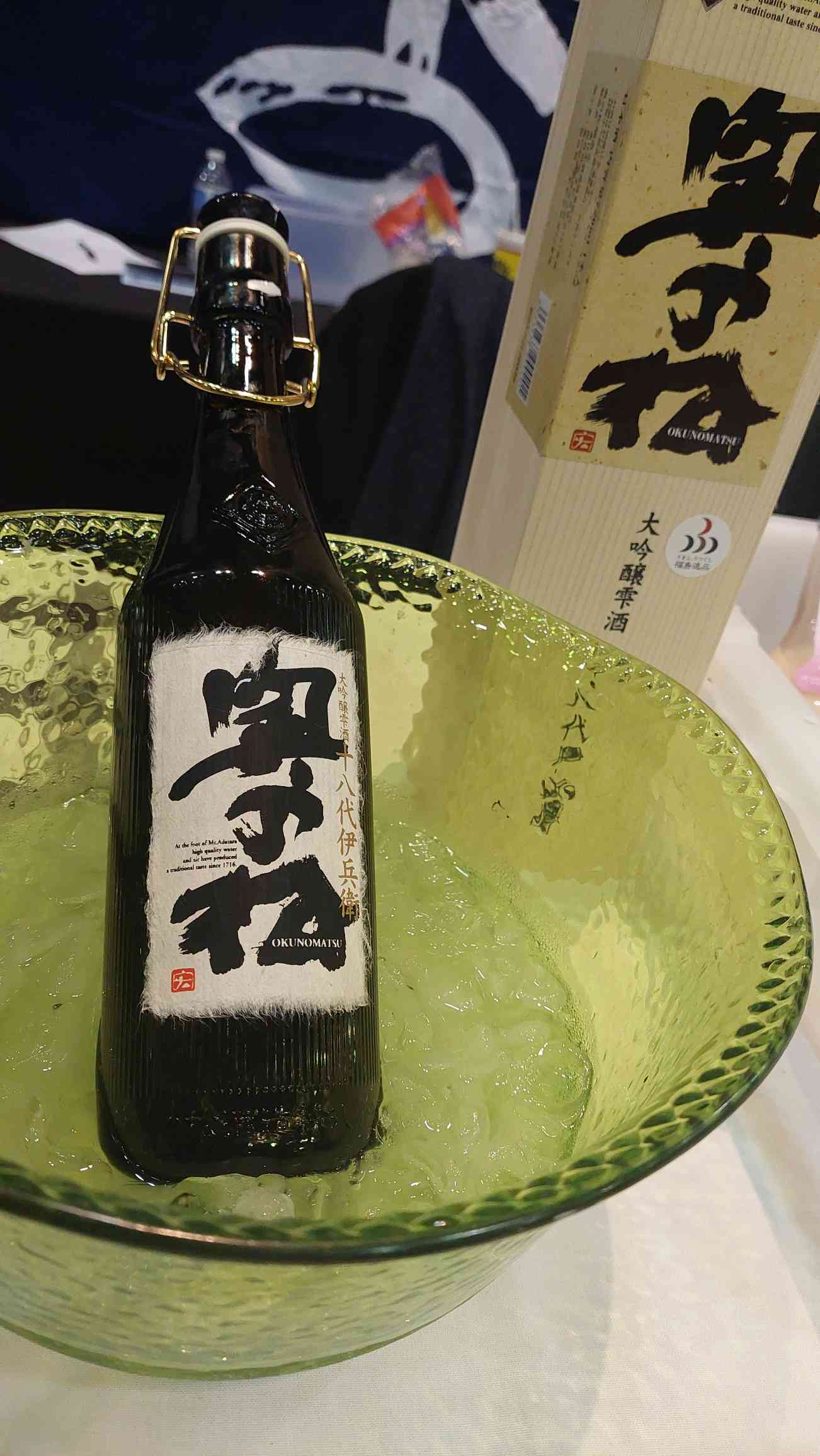

One thing that stood out to me, was how the water used for brewing was viewed as integral component for sake, and places with very soft water, like Hiroshima, make very subtle, gentle sake, while places with hard water such as from Nigata, are spicy and full bodied. I’ve been around wine quite a lot recently, but I planted my roots in beer and brewing, so I know that water profiles are very important to fermentation. Harder water contains nutrients for the yeasts, and allows for a more robust and intense fermentation. Just about every sake label has something on it about the water they use, front and centre. In fact, one of my favourite producers boasts one such label, “At the foot of Mt. Adatara, high quality water and air have produced a traditional taste since 1716”; Okonumatsu.

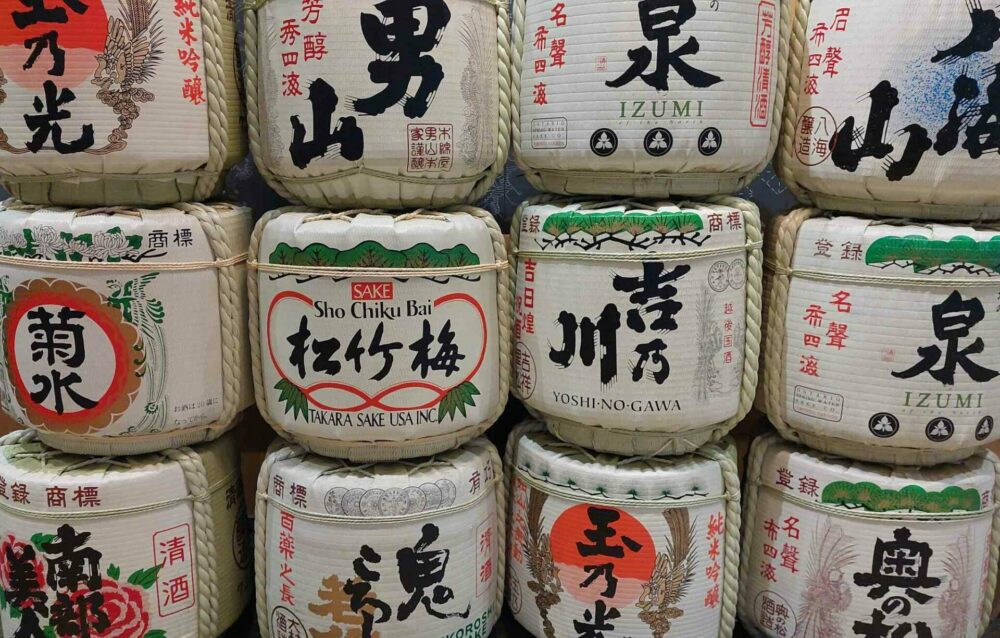

A wall of traditional sake barrels, or “Komo-daru”, line the wall welcoming guests to the event

A brewer from Fukushima, Okonumatsu is one of the brands represented by Kado Enterprise, who brings in quite a lot of LCBO available sake, which is why I knew Okonumatsu at all. This was my first lightning bolt producer, the turning point in quality, and Okonumatsu’s Adatara Ginjo is a bottle I have checked the LCBO for every single time I go into one, and never saw again. But that’s ok, because the sakes I did get to drink at Kampai more than made up for it.

The crowning jewel of the Okonumatsu line, the “Ihei” Junmai Daiginjo, is an incredibly subtle yet unctuous sake with layers of soft floral flavour and a finish that goes on forever.

I did succumb to my curiosity and deviate from my plan a few times, mostly for sparkling sake. One particularly wild invention was a sparkling sake done in the ancestral method, nearly pet-nat style, with a decent amount of lees aging. The sake, Masumi Origarami Sparkling Junmai Ginjo, was fruity, deeply textured, and full of toasty earthiness and lactic tang, reminiscent of Manchego cheese. I’m recommending this almost purely based on how much fun it is to drink, and I can’t get over imagining it alongside a cheese pizza or charcuterie board.

Sake has a unique place beside food in a way I’ve never experienced before.

Sake plays on Umami, that savoury buzzword of the food world, and often a perplexing opponent to wine. Umami is the core 5th taste, the meatiness in dried mushrooms, anchovy paste, and of course MSG. In a lot of cases this flavour, when strong enough, can amplify bitterness and astringency in wine pairings.

Sake has no such problem, it flourishes in the face of Umami. As I write I am drinking Okonumatsu Daiginjo Junmai with a 16 month aged Red Leicester cheese, and it is wonderful. The sake just brings out all the sweetness, richness, and subtle fruity flavours of the cheese.

Sake doesnt just work with food, it completes it. It has a way of pulling out new complexities, new flavours. It lifts the dish. Even something as simple as simmered burdock root became full of flavour and complexity when I had it with the “Yamatan Masamune” a Ginjo brewed by Yagi Shuzobu in Ehime.

I’ve been focusing a lot this year on mating wine with umami heavy dishes, and while there are phenomenal wine pairings and breakthroughs, sake just fills the role so effortlessly, it’s hard to deny it its purpose. I had intended to drink more sake this summer, but now I realize I should be drinking it in the winter. Sake is not just made for sushi and fresh bright flavours of the coast, the inland areas of Japan such as Hokkaido traditionally would have limited access to fresh seafood, and receive one of the heaviest snowfalls in the world during the winter. Their sake evolved to be paired with cured and preserved fish, powerful aged miso, and grilled meats. The brewing and culinary history of each region is inseparable. I’m forcible stopping myself here from writing any more, for your sake (the other sake) and mine, dear reader. Lets talk about the future ahead of us.

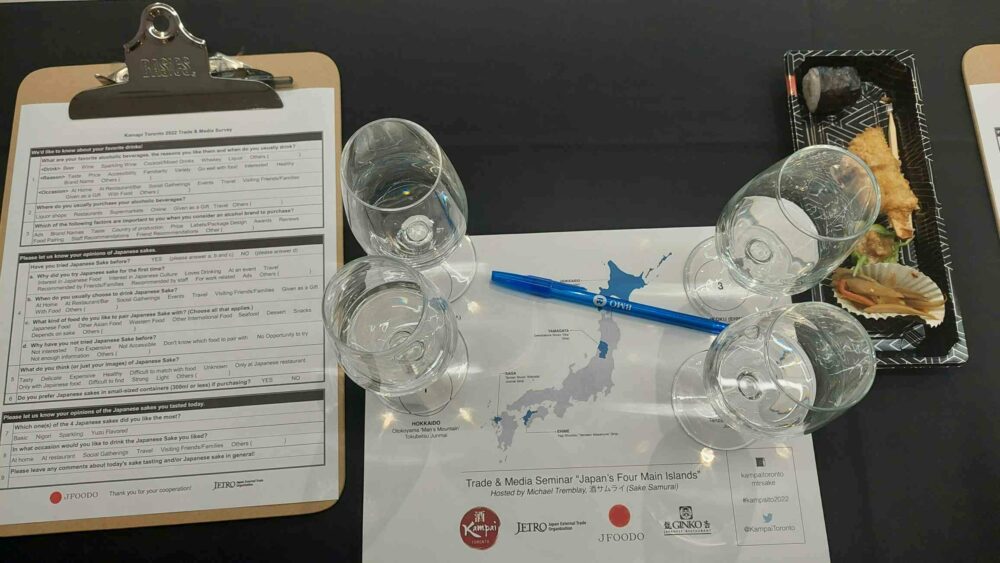

Guided by the one and only Michael Tremblay, a flight of four, each with its own food pairing.

The greatest barrier to the popularity of sake in Ontario right now is availability. One of the things that struck me the most, is how little I know about sake considering I drink just about as much of the stuff as I can get my hands on. I check the sake section every single time I walk into an LCBO, only to be greeted by the same handful bottles nearly every time.

There are specialty LCBO’s, like at Steeles and Markham road, which are better stocked, but the average location has very little to offer by way of true quality sake.

A new wine drinker can walk into any local LCBO, and usually find a solid offering that decently represents each main region. It’s sad that a new drinker interested in sake, will walk into an LCBO and their best bet is the kind of sake I buy to cook with. I spoke personally with several representatives of Canada’s sake importing groups, and heard complaints about the LCBO’s internal complexity and practices from just about everyone. The LCBO favours the middle-ground, stocking sakes that are widely distributable and targeted towards the casual consumer, but there are no standouts in middle-ground; and man, are there some serious standouts out there.

Sake is slowly but surely blowing up, with sales in Ontario up 10% from 2020 to 2021, making sake the LCBO’s next big target for their Destination collection, but as of now there’s a long way to go.

Before I wrap this up, there is one other big divider between sake and its other boozy brethren.

I wrote before that sake is an island unto itself, that it is completely unique and stands alone, but that distinction is also its limitation. Sake is almost exclusively paired with just Japanese food when it comes to restaurant offerings. Imagine if you would, that beer is only served at German restaurants, wine at French, and whiskey at American joints. It’s insane to even entertain the idea, all of these drinks come from hundreds of different cultures and places, and the intermingling of different pairings between cultures is what makes food and alcohol so interesting together.

Rice is not exclusive to Japan, and just like the Uzumi brewery making sake here in Ontario, sake breweries are popping up all over the world to meet the new demand. Sake will never truly break though, until you can walk into a Spanish tapas spot and order sake by the glass. It feels almost insane to imagine, but stranger things have happened, and as the empty bottle in front of me reveals, it is simply too good to pass up.