Pumpkin Spice Chocolate, photo by Theo Crazzolara via Flickr CC BY 2.0

Hooray for Pumpkin Pie!

It’s that time of year again, the season of pumpkin spice latte wars. “A gentle reminder,” read a friend’s Facebook post, “to be kind to those who enjoy pumpkin spice lattes even if you don’t.”

The pumpkin spice latte, otherwise known as the PSL, is an autumnal Starbucks extravaganza. Named for the cinnamon, nutmeg and clove spice blend inspired by traditional pumpkin pie seasoning, it hit the coffee counters 20 years ago and has since sold around half a billion beverages in the USA alone. (Recent recipe revision at Starbucks notes that the flavour shot now includes actual pumpkin!) It also started a pumpkin spice craze, with businesses of every ilk looking to cash in on the fervor- pumpkin spice candles, pumpkin spice bubble bath, pumpkin spice popcorn, pumpkin spice cough drops, pumpkin spice whiskey.

Not everyone is enthusiastic about PSL season. There are definite yay and nay teams for the phenomenon. Perhaps because the rise of the PSL coincided with the rocket trajectory of Instagram and other social media, it became both the subject of way too many cute fall sweater posts and object of derision for trolls. Memes about class, privilege, gender and race abounded, accusing PSL lovers of all kinds of nefarious misdeeds. Thus, a mountain was made from a molehill, and became an iconic cultural symbol.

On the one hand, the pumpkin spice latte was a tasty treat that ushered in the end of summer and transition to fall. Whether one enjoyed this particular recipe of syrup and espresso was no more or no less important than the Early Grey versus Orange Pekoe preference. On the other hand, the pricey liquid confectionary was viewed as bombastic, indulgent, capitalist, and white. For some, it was the ultimate symbol of a privileged class of women, the kind who wore Uggs to drive to yoga and carried tony handbags with teacup dogs inside them.

Miss October, waiting for the Great Pumpkin! photo by Deb, Montoursville, PA , in the beautiful Susquehanna Valley of central Pennsylvania, USA, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

It wasn’t just mean memes. An academic paper on “The Perilous Whiteness of Pumpkins” made the rounds. WaPo weighed in more recently on the problematic history of nutmeg: “Pumpkin spice wars: the violent history behind your favorite Starbucks latte,” read the ominous headline, with the tagline, “PSL is back, and so is its connection to a centuries old genocide.” BuzzFeed opined, “To consume and perform online in a basic way is thus to reflect a highly American, capitalist upbringing. Basic girls love the things they do because nearly every part of American commercial media has told them that they should.”

The backlash had a backlash, too, of course. Hating the PSL craze was all about hating women, disguised as virtue. Rebecca Jennings wrote in Vox last summer, “Essentially, hating pumpkin spice lattes is our way of othering those who drink them…”

But long before anyone had heard the phrase “pretty privilege” or began posting the excruciating minutiae of their every daily coffee break and wardrobe change on Instagram, pumpkin spice enmity was a thing. Centuries ago, pumpkin pie was a symbol of abolitionism, the choice of the states who fought against slavery. Southern states viewed pumpkin pie as a taste imposed on them and clung to their penchant for pecans and sweet potato pies.

Still Life with Pumpkins and Onions, by Ida Pulis Lathrop (USA) before 1937

The discussion over the meaning of Thanksgiving in the context of colonialism and America’s indigenous peoples continues today, with many criticizing the holiday’s historic legacy as the erasure of the cultures of America’s original peoples. Traditional perspectives on the holiday celebrate friendship between European immigrants and the Indigenous folks who welcomed them and helped them acclimatize to the challenges of the land. Sharing the autumn harvest together and mutually giving thanks is, in this view, a holy-day indeed.

As with many things, perhaps either view is not the whole truth and nothing but the truth. Neglecting the vicious cruelties of the settler past is unconscionable. But Thanksgiving was also an important holiday in the history of the abolition of slavery. Pumpkin pie is the enduring symbol of that holiday. Thanksgiving was a 200 plus year tradition in American when Abraham Lincoln, the abolitionist who issued the Emancipation Proclamation, made it a national holiday in 1863, a day set aside for “thanksgiving and praise.”

Harper’s Bazar Thanksgiving, 1892

The jewel of the Thanksgiving table, pumpkin pie, was a frequent symbol in women’s abolitionist literature, including the 1827 anti-slavery novel, Northwood, by Sarah Josepha Hale. Hale worked tirelessly for decades to declare Thanksgiving a national holiday, and in her book, pumpkin pie was the star of the dessert cornucopia: “the pumpkin pie occupied the most distinguished niche.” A famous poem from 1842 by abolitionist Lydia Maria Child ended with “Hurra for the pumpkin pie!”

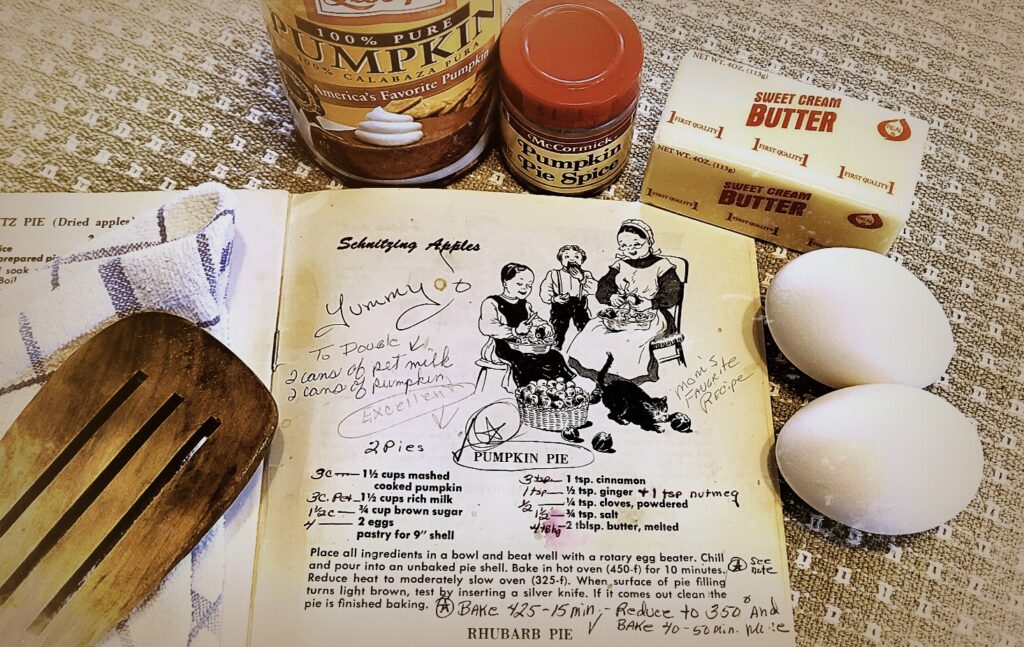

Old Amish Cookbook, by JLS Photography Alaska CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Deed via Flickr

Whether it is currently an emblem of abolition or of the privileged classes, pumpkin pie is an absolutely American cuisine, with a blend of Indigenous and European roots. “Pumpkin” usually refers to medium to large sized round squashes growing in America and Mexico and Central America for around 9000 years. The word probably comes from “pohpukun” in the Wopanaotooaok language of Massachusetts. (Our word “squash” is from the Narragansett word, “askutasquash.”) Many sources, including the Oxford English Dictionary report that the word pumpkin is also from the Greek, “pepon,” for “melon,” or from the French, “pompion,” a term that poetically describes squash touched by the sun.

Pumpkins didn’t become “pumpkin pie” the way we know it until the squash journeyed back to Europe with Dutch and French settlers, making its way to England, and returning to New England.

The first pumpkin pies in the region looked a lot different from today’s. They were more of a stew, with blended sweet and savory ingredients, cooked right inside the pumpkin shell. Eventually, this meal turned into dessert, with a custard and pumpkin pulp blended on top of pastry. Many early versions were recorded as “pumpkin puddings” and did not always have crusts.

Pumpkin pie in one form or another appeared in French, English and Dutch cookbooks, dating back to the 1600s. This one, combining pumpkin with currants and those contentious pumpkin spices is from Hannah Woolley’s The Gentlewoman’s Companion in 1675. “Take a pound of Pumpion, and slice it, an handful of Time, a little rosemary, sweet marjoram…take cinnamon, nutmeg, pepper, and a few cloves…also ten eggs, and beat them all together with as much sugar as you shall thin sufficient….take apples sliced thin round ways…with currans betwixt the layers, be sure you put in good store of sweet butter…”

Pumpkin Pie by David Goehring CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Today, the best pumpkin pies are plain, almost homely: just a decent pie crust, filled with a smooth brown blend of mashed pumpkin, eggs, cream, sugar, butter and nutmeg, ginger, cinnamon, and cloves.

The early immigrants learned how to eat pumpkin from the original inhabitants of the land. Pumpkins, and squash in general, were one of the “Three Sisters” of Indigenous American agriculture. For the Iroquois, the Three Sisters were maize, beans, and squash, three spiritual gifts that sprouted from the Sky Woman’s daughter to sustain life.

Even before the cultivation of corn or beans, pumpkins were a staple food and crop for numerous Indigenous tribes of the regions, including the Pueblo, Apache, Hopi, Navajo, Pima and others. Southwestern tribes scooped out the seeds and toasted them, covered them in chile powder, and ate them with a mixture of nuts and fruits. It was a kind of early granola. The flesh was commonly cut into chunks and roasted in ovens or over coals, straight up. Mashed pumpkin was popular everywhere. And slices of the bulbous squash were cut and tied to the rafters to dry and provide nourishment through the long winters.

A Field of Pumpkins, Oregon, photo by Kirt Edblom CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr 2016

One cup of pumpkin flesh contains over twice the full beta-carotene needs for the day, more than a third of the vitamin K, almost as much copper, almost a quarter of the vitamin E needed, a fifth of iron, 13% of magnesium, and a good wallop of riboflavin, B6, C, and potassium. There are also loads of lutein and zeaxanthin, which along with the beta-carotene are three different sisters, essential nutrients for eye health and clear vision.

Pumpkin Puree Soup, by Marco Verch Professional Photography CC BY 2.0 Deed via Flickr

While most modern North Americans only consume pumpkin in lattes and pies, this big orange berry is a hardy vegetable that now grows all over the world and has become a prized part of planet-wide culinary history. Pumpkin curry is a defining dish in Myanmar, with veggie cubes sauteed with herbs and peanuts and chicken and tossed in tamarind, garlic, and onion. In Zimbabwe, nhopi is a beloved pumpkin porridge, mashed with peanuts and corneal. Mexico enjoys calabaza en tacha at Day of the Dead celebrations, a candied pumpkin delicacy. Bundavara is a Serbian pastry with pumpkin stuffed phyllo sheets. Challaw kadu is an Afghani stew with pumpkin and meat in yogurt sauce. In Russia, they have Olad’i iz tykvy, a kind of pumpkin pancake served with honey and sour cream. Fanesca is a traditional cod and pumpkin soup from Ecuador. Creamed pumpkin soup has variations all over Africa. In Botswana, it is blended with apples, herbs, butter, and cream, and served with antelope or other game. This is a favourite soup of Mma Ramotswe, the wonderful “traditionally sized” detective in Alexander McCall Smith’s series, The Number One Ladies Detective Agency.

Pumpin Pancakes with Honey, by Elena Leya via Unsplash

If you adore sushi and sashimi, chances are you’ve already had Japanese pumpkin. The kabocha squash is a familiar ingredient in the popular tempura appetizers. It is also a welcome guest in roasted lotus root and kabocha salads, and in crunchy kabocha cookies.

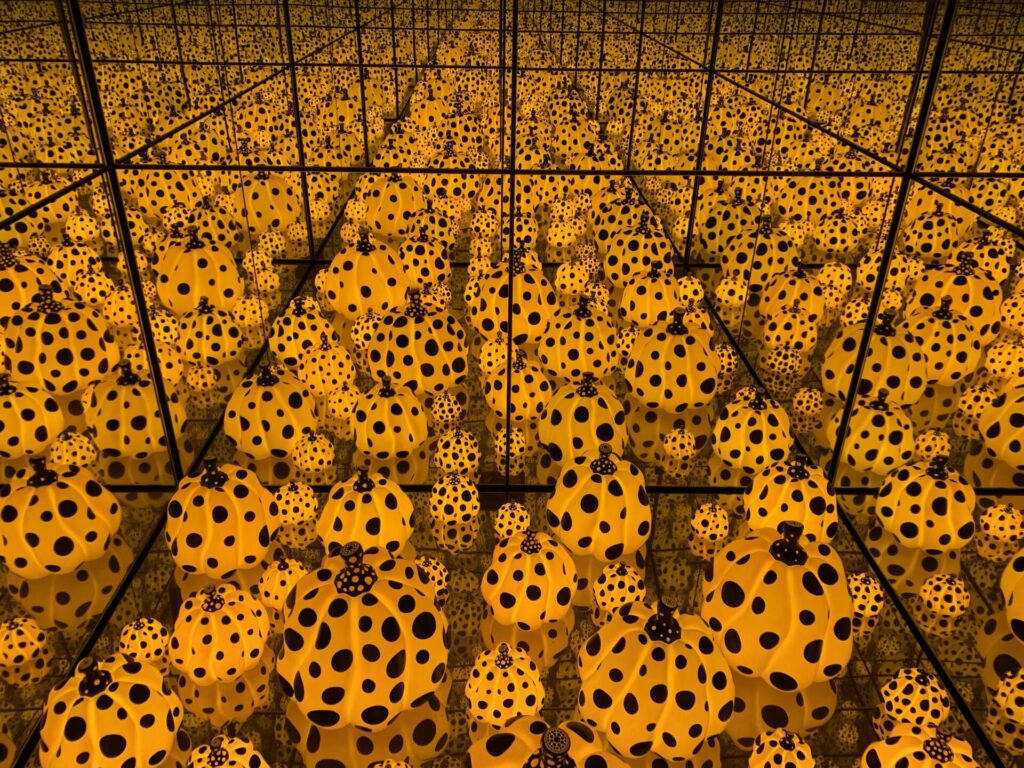

But Japan’s most famous pumpkins belong to the artist Yayoi Kusama. The nonagenarian is the world’s top selling female artist, and thanks to her endless production of polka dots and pumpkins, often combined, she is a household name today all over the world. Kusama has been working with these motifs since she was ten years old, bringing them to America and taking them back with her. She paints dots to contend with lifelong hallucinations or rolling fields of dots, creating “infinity rooms” with mirrors to intensify the volume of the dots, to show us how her visions were about the fear of being obliterated by the dots and to take command of them by making them beautiful. Kusama chose to live in an institution for people with mental illness since her return home in the 70s, because she feels safe there. She leaves every day to work in her studio.

Kusama has reconciled her terror of being engulfed by the incessant flow of polka dots with the realization that though we are each just a dot, unnoticeable in the cosmos, we are part of a thrumming sea like the stars.

The Spirits of the Pumpkins Descended Into the Heavens, by Yayoi Kusama (Japan) 2015 Photo by Ncysea CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The pumpkin motif is recurring because it brings her comfort. The artist has auditory as well as visual hallucinations and has heard plants speaking to her since childhood. In her autobiography, Infinity Net, Kusama writes, “The first time I ever saw a pumpkin was when I was in elementary school…Here and there along a path between fields of zinnias, periwinkles, and nasturtiums, I caught glimpses of the yellow flowers and baby fruit of pumpkin vines. I stopped to lean in for a closer look, and there it was, a pumpkin the size of a man’s head. It immediately began speaking to me in a most animated manner. It was still moist with dew, indescribably appealing, and tender to the touch.” Kusama “was enchanted by their charming and winsome form,” the “generous unpretentiousness” and “solid spiritual balance.”

She was still a teenager when she painted a picture of pumpkins for an exhibition and won a prize. After this, she began sitting with “the spirit of the pumpkin,” and meditating on the matter. “Just as Bodhidharma spent ten years facing a stone wall, I spent as much as a month facing a single pumpkin.” Though she painted her first pumpkins in the 1940s, it was half a century later that the squash became synonymous with Yayoi. Mirror Room (Pumpkin) was a patch of polka-dotted pumpkins magnified into infinity. Today, the artist is often seen wearing an orange dotted pumpkin dress.

Like Kusama, most of us find pumpkins jovial and reassuring, the PSL notwithstanding, with pumpkin pie as the ultimate in comfort food. There was even a Great Pumpkin in the Peanuts comic strips, a beloved but never seen being waited on in vain by Linus every year in a pumpkin patch. The Great Pumpkin was a symbol that both poked fun of foolish faith and acknowledged the human longing for spiritual connection. But the American pumpkin that brought sacred sustenance for millennia took a more sinister turn to become the terrifying jack-o-lantern, representing restless, tormented souls caught between the worlds.

Halloween Greeting, Gibson Cards, 1910

Like most everything, the jack-o-lantern is a syncretic concoction of various ideas, legends, stories, appropriations, and cultures. Its origins are multilayered and resulting meaning is vague. The name basically means “the man in the lantern.” One origin is from swamp gas flares on bogs in old Ireland, where legends about will’o’the’wisps, or restless spirits carrying lanterns over the swamps and moors, were born. More or less simultaneously, stories about the lantern carrying spirits evolved to perceive them as “night watchmen” who would keep the evil spirits away. There were folktales about Jack selling his soul to the devil, and others about putting spirit lanterns in the window to banish evil from the home. It was a new form of a much older practice of apotropaic magic, using objects to ward off evil or misfortune. Of course, there were more evil spirits wandering about at Samhain time, of course, when the veil was thin.

It was a common folk custom from Europe to Africa to carve symbolic personalities into vegetables, and the Irish gave old Jack a face in the form of the turnip. For a while, Jack was called the McLantern. The jack-o-lantern was a turnip in old England, too, in the late 1700s, then named Hobberdy’s Lantern. Similar lamps were also used to ward off vampires.

In North America, the traditional turnip lantern was retired because the pumpkin was big as a man’s head and roomy, much more suitable for lanterns with both practical and supernatural purposes. The popularity of the jack-o-lantern really took off once illustrations of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, a much-loved ghost story by Washington Irving, began showing the headless horseman carrying a pumpkin in place of his own severed head. Jack-o-lantern carving became a popular Halloween tradition and art, with all manner of intricate, tormented faces created to boo away unwelcome ghouls.

Jack’o’lantern Spectacular in Louisville, photo by Lou Oms, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The one subject we haven’t touched on is pumpkin beer. There’s another liquid gold that rivals the volatility and love hate divide of the PSL fall rollout, and it’s the annual orange craft beer. No one is neutral on this subject- you either love the taste or despise it.

Pumpkin beer is derided as often as it is cheers!ed, for being too sweet, too orange, and too hipster-crafty. Many champions of both pumpkin and beer believe they simply don’t go together. Or, to quote that half of the Internet, “Nasty.”

Curiously, the golden glow of this autumnal cerveza was not invented by the trendy local brewery guys who use charcoal and clove facial oils on their manicured beards and sport Group of Seven socks. Pompion Ale was first brewed commercially in the ‘80s, several decades ahead of the Starbucks spectacle in sugar and foam. But it was the pragmatic colonists again who came up with the idea a long time back. Fermenting pumpkins to make booze was due to the squash’s simple abundance and constant shortages of malt. An ancient ditty known as America’s first folk song lamented the annual pumpkin surplus, singing, “We have pumpkin at morning and pumpkin at noon,” and concluded that at least they could be made into liquor.

Dear reader, you may or may not be wondering where I stand on these very important issues. Full disclosure: pumpkin spice lattes- a firm no. Pumpkin beer- I enjoy them, but rarely. I have enjoyed jack-o-lantern carving with my small friends. I love African pumpkin soups and the amazing detective Precious Ramotswe: I’ve read all of the books in that series!

I actually have a tattoo that says “pumpkin”- “Daddy’s little pumpkin,” to be exact, etched onto my bicep in memento mori, to match a small medallion my father made for me when I was wee, and still have, just in case I ever lose it.

I adore the feisty, fascinating Yayoi Kusama and her pumpkin patches. And I adore the Peanuts, especially Linus (I still have my musty and tattered security blanket somewhere!) And yes, ‘tis the season now to enjoy the greatest pumpkin of them all: hurray for pumpkin pie!

The Harvest of Pumpkins, by Francesco Paolo Michetti (Italy) 1873