For over a decade or so, I have observed that as a culture, we are becoming less and less attached to the earth that supports us with each passing day, and indeed, it was co-founder Malcolm Jolley’s and my own mutual concerns about this that led to the founding of Good Food Revolution way back in 2009/2010.

Today, when we get hungry for protein, most run to the supermarket and pick up a pack of shrink-wrapped meat, seldom giving a second thought as to how that meat got to the grocery shelf. And so, with a view to getting closer to the source of my food than most would be comfortable with, I decided in the fall of 2016 (mere days after the US election—no coincidence there) to learn how to hunt.

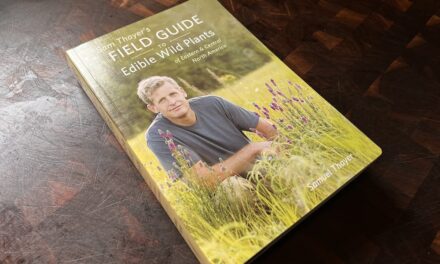

Running in parallel to my new-found interest (read: midlife crisis) came a related passion for self-sufficiency that, upon occasion, flirted with the concept of survivalism. Being a voracious information sponge, I gorged upon mountains of books and websites, and in my deep dives, I read over and over again that if the world did really fall apart and one had to live off the land, it wouldn’t be big game that one would be surviving upon; it would be the smaller critters: rabbit, hare, squirrel… and in the case of one of these pieces, the lowly frog, but for the most part, it would actually be edible plants.

As a child growing up in Scotland in the 1970s, my first introduction to rosehips was either using them as makeshift munitions in catapults (read: slingshots) or using them as ersatz itching powder, ripping them open with our grubby wee hands and stuffing them down the shirts or underpants of the day’s unfortunate soul. I often wonder if the children of today indulge in such simple, free pleasures with the plentiful rosehip.

The wild rosehip (or rosehaw) is the fruit of the wild rose, and as there are two dozen species found across North America, for the purposes of this piece, we are going to be talking about the Rosa canina, or Dog Rose, a European import, and in the minds of many foragers, the best tasting of the rosehips found here.

Also, keep your eyes peeled for Rosa multiflora, a more commonly found invasive species (native to Asia) with a decidedly tangy flavour. They can easily be told apart, with the former usually having pink-flushed white flowers and the latter having much smaller white flowers, although it’s a little more tricky to distinguish between the two later in the season when all the flowers have long gone. Saying that, either of these will fit our ambitions here.

I’d been pondering experimenting with rosehips for quite some time, but it was only upon catching a bad dose of COVID (my very first) that I set out determined to create some type of immune-boosting tincture. Just before the new year, I set out in the snow to check out a rosehip bush I had spotted a few years earlier, and thankfully, even this late in the season, the fruits were still harvestable.

It’s probably worth noting not to leave it too late, though, as remember, you’ll be competing with some canny avian characters who know exactly when to devour hips at their finest.

Eschewing the more dessicated and discoloured hips, I set to work, harvesting around three cups of them. It’s best to wear a pair of gloves and an old jacket with sleeves, as the barbs on the branches can be quite vicious; my older Moncler jacket is much the worse for wear after this particular forage.

The hips are a hell of a lot easier to clean than both rowan berries and autumn olives, and for this I was most thankful, as the lengthy cleaning of berries is certainly not one of my favoured pastimes. For the most part, it is simply a matter of snapping off any stems and giving them a good couple of rinses in a colander.

Toss the cleaned hips into a saucepan and simply cover with water and bring to the boil. Once boiling, turn down the heat to medium and set to work with a utensil like a potato masher to break down the rosehips. Some suggest using a hand blender for this, but picking them “late harvest” meant that much of the fruit had already begun to break down “on the vine”.

Some suggest adding some fresh ginger root to the mix at this point, but I think I prefer the unique flavour of rosehips unadulterated. Perhaps I’ll make a batch with the addition of ginger in late 2024 and report back.

I would recommend leaving this simmering for a good 15 – 20 minutes and then allowing it to cool for 30 minutes before straining the mixture through a cheesecloth. Be sure to squeeze the cheesecloth to get the most extract from your rosehips, as we aren’t worried about any lack of clarity here. I rather like the turbidity that this step of the process adds to the final product.

The rosehips lose much of their bright crimson colour through the cooking process, but you’ll end up with a delightfully rusty, bright orange liquid that is rather tart to the taste but full of pure concentrated rosehip flavour. Personally, I rather like it in this form, but it does become much more palatable for most with the addition of some quality local wildflower honey.

I took one jar of clear, runny honey from a local producer and poured it into a saucepan. After adding the rosehip liquid, I brought the pan to a boil and then reduced the heat to simmer for some time, reducing and concentrating the liquid by around a third.

Be very careful about boiling your liquid over here. If you take your eyes off the boiling rosehip liquid and honey for a moment too long, you may end up with some pretty nasty scars on your stovetop (see above). It sure does smell superb though, in a charred-medicinal-caramel kind of way.

After reducing your liquid and allowing it to cool for around 30 minutes again, using a funnel, carefully distribute your tincture between as many sterilised glass vessels as you can fill. Some suggest adding lemon juice just before cooling, but unlike jelly-making, I’m not really looking to add any additional pectin at this point, so I chose to omit this step.

The resultant “tincture” has a unique flavour; the honey is augmented by a hint of apples and a fascinating wild, herbal, slightly ferrous sapidity that my family finds to be utterly delightful. We enjoy it medicinally by the teaspoon, over ice cream, in herbal teas, in hot toddies, and as a glaze on pork, lamb, and poultry.

Wild rosehips are particularly high in Vitamin C as well as containing the carotenoids beta-carotene, lutein, zeaxanthin, and lycopene.

Let’s just hope that this works to kickstart my utterly battered immune system this month.