Good Food Revolution Health Warning:

Before we go any further, please do not consume any wild mushrooms unless you are 100% sure that it is safe to do so.

Be sure to have an expert confirm the identity of any mushroom you find in the wild.

If you are in any way unsure, please err on the side of caution and live to forage another day.

All edible fungi MUST be cooked before ingestion.

For over a decade or so I have observed that as a culture we are becoming less and less attached to the earth that supports us with each passing day, and indeed it was co-founder Malcolm Jolley’s and my own mutual concerns about this that led to the founding of Good Food Revolution way back in 2010.

Today, when we get hungry for protein, most run to the supermarket and pick up a pack of shrink-wrapped meat, seldom giving a second thought as to how that meat got to the grocery shelf. And so, with a view to getting closer to the source of my food than most would be comfortable with, I decided in the fall of 2016 (mere days after the US election – no coincidence there) to learn how to hunt.

Running in parallel to my new found interest (read: midlife crisis) came a related passion for self-sufficiency that upon occasion flirted with the concept of survivalism. Being a voracious information sponge, I gorged upon mountains of books and websites, and in my deep-dives I read over and over again that if the world did really fall apart and one had to live off the land, it wouldn’t be big game that one would be surviving upon, it would be the smaller critters: rabbit, hare, squirrel… and in the case of one of these pieces, the lowly frog.

This month we look at my second (non lethal) foray into the world of foraging for wild mushrooms with the Dryad’s Saddle or Pheasant’s Back.

These two smaller examples will grow to the perfect size within about 48 hours. They grow at an astonishing rate, so be careful you don’t let them get too large.

The Dryad’s Saddle is a basidiomycete bracket fungus, with the scientific name Cerioporus squamosus or Polyporus squamosus.

If you are unfamiliar with the term dryad, then please allow me to explain. In Greek mythology, a dryad was a female nature deity, a tree nymph or spirit, specifically those of oak trees, as in Ancient Greek “drys” refers to “oak”. For some reason the inclusion of dryads in one’s prose/poetry appears to be de rigueur for so many western scribes; I’m not sure what was going on, but Milton, Coleridge, Thackeray, Pound, Keats, Davidson, Lewis, and even Plath all felt the need to include descriptions of these seemingly always scantily clad nymphs in their works.

The reason for the moniker of Dryad’s Saddle for these commonly found polypore mushrooms comes from the idea that said dryads could conceivable sit upon them, and it’s true, from some angles they do look like tiny saddles… if one squints a little.

In this shot here one can see exactly why it gets the other name of Pheasant’s Back, as that does look remarkably like a pheasant’s plumage.

Nomenclature aside, these fungi are often thought of as not being in quite the same class as other gastronomic wild mushrooms, notable the morel, chanterelle, or my personal favourite, the chicken of the woods. I’ve come to understand that this is due to more mature Dryad’s Saddles being extremely tough, and whilst not being poisonous per se, they are, for all intents and purposes, completely inedible. I find that young, tender Dryad’s Saddles are utterly delicious, and so personally I highly rate this mushroom as a true spring (and occasionally, fall) delicacy of the forest.

As the fruiting bodies of these mushrooms can range from smaller than your palm to larger than your outstretched palm, it’s also important to note here that size doesn’t always indicated age. If you can cut through the mushroom’s tender white flesh easily with your foraging knife (though not necessarily the stem), then you can be assured that you have uncovered a younger example.

If you are having trouble cutting through the flesh, or it is darker in hue, then that mushroom is too far gone for standard culinary use; although, saying that, tougher, older examples can be tossed in the stockpot or thinly sliced, placed in a dehydrator, and then powdered, as an addition for soups etc. Waste not, want not, and all that…

It’s very important to use the unusual pores (not gills) to identify this particular mushroom correctly. The pores are not circular in their shape but strangely angular.

If you are out looking for morels in the spring months (April/May), you’ll find yourself looking at the ground a lot, but it is at this time of years that the Dryad’s Saddles also begin to emerge, so be sure to look up the trees you pass now and again to find these wonderful bracket fungi. You’ll find them not only on dead trees and stumps, but also growing parasitically upon living trees (mostly hardwoods such as elms and tulip poplars). Once you start looking, you’ll probably be amazed just how prolific they are in Ontario, and indeed most of eastern Canada.

Much like the Chicken Of The Woods, they are quite simple to identify correctly, and as they have no poisonous lookalikes, they are one of the safer wild mushrooms to go foraging for.

There is, however, one toxic mushroom that is occasionally mistaken for the Dryad’s Saddle (although I cannot work out why), and that would be Turbinellus floccosus, or the Wooly Chanterelle. It’s easy to distinguish these from the Dryad’s Saddle, however, as they are not found on trees, and have gills instead of pores on their undersides.

Saying all that, make sure that you go through this checklist to correctly identify a bona fide Dryad’s Saddle:

- This mushroom is always found on trees, stumps, or logs, and NEVER on the ground.

- Dryad’s Saddles have a fan or kidney-shaped fruiting body on a short, stubby stalk.

- The top of the cap is covered by concentric rows of thin, peeling brown scales, hence the alternative name, Pheasant’s Back.

- The flesh within the cap is soft and white and does not discolour when cut.

- Younger examples have white, tender flesh. Older examples have darker, corky, tough flesh.

- This flesh, when cut, has an absolutely unmistakable aroma of cucumber/watermelon that is really quite enchanting. Some actually call this the Cucumber Mushroom.

- The underside of the cap is covered in white/cream pores, not gills.

- These pores are angular in nature, and not round. Almost honeycomb-like (see pics above and below).

- If you are getting serious about foraging you’ll probably want to do a spore print: the Dryad’s Saddle gives us a white spore print.

- Like all wild mushrooms, Dryad’s Saddles MUST be cooked before ingestion.

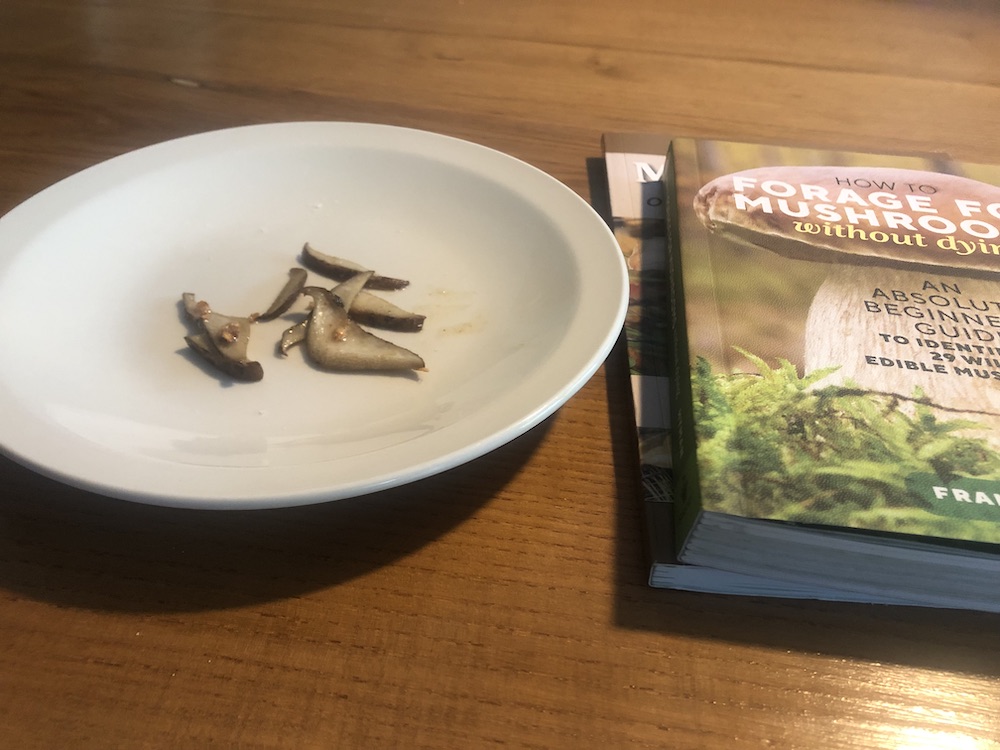

Testing a tiny piece of the Dryad’s Saddle the night before serving them to family and friends. Best to err on the side of caution and try them out yourself first.

Another word on when it comes to harvesting these beauties, it’s important to understand that this particular mushroom is capable, given the right conditions, of growing at a simply astonishing rate.

Often I’ve spotted some tiny, young Dryad’s Saddles emerging from a tree, only to return a few days later to find that they have grown into enormous brackets that are now too tough to be cooked normally. I’ll admit that it is tricky to gauge exactly when they’ll be at their best, but I’d rather harvest some smaller examples than miss out on the opportunity entirely.

In this shot you can see again this mushroom’s unusual angular pores on the underside, almost like a honeycomb.

Some foraging guides advise to peel off the top layer or the pore layer of the mushroom before cooking, but in my experience one can use the entire fruiting body as long as you manage to catch a young example. You may wish to cut off any of the tougher, corkier flash from close to the stem though.

When it comes to preparing Dryad’s Saddle, I find, as is often the case with foraged stuff, the simpler the better:

I’ve had most success with a simple sautée in butter with a little garlic, salt and pepper. Excellent served on crostini with a sprinkling of parsley, thyme, rosemary.

Alternatively one can place slices of Dryad’s Saddle on a parchment paper-lined cookie tray with olive oil, sea salt, thyme, and cracked pepper and placed in a 350 F oven for around 15 minutes.

Although I have never experimented with a tempura preparation, there are many online who swear by it.

As with all wild mushrooms, I usually take a small piece and cook it for myself on the first night, waiting to see if I go through any adverse effects before daring to prepare for family and friends the next day.

A word of warning, certain individuals may have personal gastric sensitivities to some of the compounds found in wild mushrooms, so don’t go nuts and serve your guests huge quantities of anything fungal you find in the woods.

A simple mis-en-place for serving them sautéd in butter with garlic on toasted baguette with melted cheese and a side salad with a piquant dressing.

All in all, I find the Dryad’s Saddle to be a truly under-appreciated woodland treat.

Captured young, they are a real delight, and that ephemeral cucumber/watermelon aromatic is a real olfactory pleasure to experience as one harvests them.

Happy (and safe) foraging.

Et voila, a delicious little appetizer utilizing the spring harvest of Dryad’s Saddle.

Postscript: Since publishing this piece I have come to discover that Dryad’s Saddle mushrooms are MUCH better if consumed within a day of harvesting, as they have a tendency to get disgustingly tough and rubbery if left in the fridge for longer than this.