The Princess Aubergine: Eggplant Love Around the World

Eat. Play. Rove. with Lorette C. Luzajic

The eggplant, comically named star of the garden, does not typically look like an egg. Rather, the word is synonymous with deep purple, as big and bulbous as a football or clown shoe.

There are indeed small white cultivars, not very common today, and large white ones, too; around the world, there are green and yellow and orange eggplants, and every shade of violet. They come round and knobby and long.

More often called “aubergine” in Europe, this more regal and French sounding nomenclature is neither, but is derived from Sanskrit roots, telephone-game style through Persian, Arabic, and Spanish incarnations, and means “that which removed windy humours.” The noble eggplant is named after ancient Ayurvedic cures for flatulence.

The jumbo bruise-blue fart banisher has an equally undignified name in Italian, where she is called the melanzana, the insane apple. The eggplant is, after all, poisonous, and was believed to cause madness.

This complicated reputation comes from the fact that, like potatoes and peppers and tomatoes, the eggplant is a relative of the deadly nightshade plant, with similar flowers to its cousin, Belladonna. This was the flower famously crooned about by Stevie Nicks, and used in salves by witches to induce hallucinatory voyages. The unpredictable Belladonna delivers outlandish visions, but can be toxic enough to kill.

Guilty by association? Not exactly. The earliest eggplants we know, in India, and we’ve chased them all over the world and found them just about everywhere, were poisonous. They were domesticated and cultivated in various efforts until they were edible. The path to today’s gorgeous baba ganoush, to stuffed aubergines, to zaalouk, to caponata, is paved with corpses.

Display of Heirloom Eggplant Varieties, Santa Rosa, Califoria Phoebe, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Historic Indian, Persian and Italian literature contain references and warnings about the poisonous aubergine. The eggplant still contains the nightshade family’s toxic alkaloids, including solanine, and so its leaves and shoots are best avoided. Traces in the fruit itself are so faint that impractical quantities would need to be consumed for toxic effects. However, some very sensitive people respond to the inflammatory alkaloid with increased arthritis pain.

Our poorly nicknamed, funny-shaped plant of ill repute also happens to be quite bitter tasting, thanks to traces of nicotinoid, just like its other cousin, the tobacco plant! Most customs insist against serving it raw, and salting or soaking before cooking to render it palatable.

Finally, the eggplant has next to nothing to offer in its vitamin and mineral profile, barely registering a single percent of the RDA per serving in most categories. It is hailed as low calorie and low carb, but it is arguably low in everything- vitamins, minerals, protein, even, truth be told, in flavour. Only copper and manganese clock in at around 10 percent of a day’s minimum, and there’s some fibre, if you’re eating lots of other plants in your ratatouille.

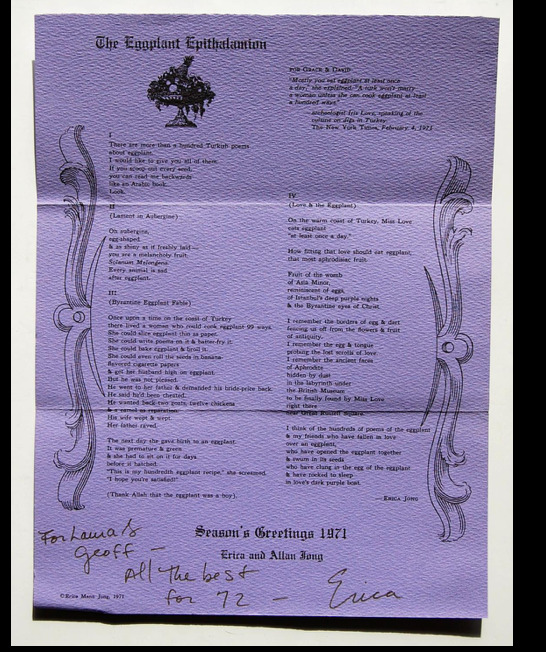

None of these feeble, absurd or toxic qualities has stopped the entire globe from rhapsodizing about aubergine. Indeed, the favourite varietal of the western world, that giant plump dark purple bulb, is called the Rhapsody. Quite a few of us in North America are eggplant obsessed, but the American continents are probably where eggplant is the least popular. In India, it is considered the “king of vegetables.” China consumes the most per capita. In Greece, it is a key ingredient in moussaka, the national dish. The Sicilians can’t even cook without it. In Turkey, “A Turk won’t marry a woman unless she can cook eggplant at least a hundred ways,” archeologist Iris Love wrote in 1971, in the New York Times, talking about the food on her digs. American writer Erica Jong wrote a whole poem about that statement, “The Eggplant Epithalamion.”

The Eggplant Epithalamion, by Erica Jong- Broad Side 1971

So what is it? What’s the deal with eggplant?

Oh, where to start?

The overarching unifier is the aubergine’s versatility. It can be stuffed, roasted, chopped into stews, pounded, pickled, smoothed, spread.

Part of that versatility is in its chameleon textures. Part is the subtlety of its flavour range. It is the eggplant’s unique ability to absorb and illuminate other flavours that make it shine. The co-star is the star.

Another epic quality is in the umami. Umami translates from the Japanese as “essence of deliciousness.” The Japanese long held that the western quadrangle of flavours, “sweet, salty, bitter, and sour,” was incomplete and lacking a category for monosodium glutamate. The elusive and difficult to describe flavour was key to satisfaction, sometimes described as “meaty” and other times as “rich and complex.” The closest we could get was “savory.”

It was definitely connected to satiety and a sense of the completeness of a meal. The controversial additive MSG always ratcheted up diner desire and satisfaction, making us describe a meal as better tasting, even as we were wary of its ill effects. But umami didn’t depend on the stuff. It depended on something we couldn’t put our finger on. We knew it when it was there: mushrooms, soy sauce, Parmesan cheese, red meats, sundried tomatoes, oysters.

Umami was a popular concept with vegetarians and vegans, because it provided something “meat like” in flavour that seemed necessary to sustain satiety in a plant based diet. Asian diets were full of it, whether plant based or animal inclusive. In 2002, scientists found umami receptors on our tongues and so it was officially added to the flavour map, now sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami. The key was glutamate, a naturally occurring protein and a complex player in our biology. It is important for making neurotransmitters, but too much causes agitation and Alzheimer’s. Too little, and our brains and bodies can’t function at all. That is all for another day, but in a nutshell, umami is indeed associated with our reward centres, and while it is true that we take in excess at our peril, there is no life at all without it.

While eggplant is much higher in glutamate than apples or arugula, it is comparable to many other vegetables like squash, peppers, and tomatoes. Adding soy sauce, Parmesan cheese, jus de boeuf and other popular accompaniments ratchet up the umami quality into the stratosphere. But the thrill is the marriage of the umami with the gooey glory that cooked eggplant becomes.

The unique richness of eggplant cuisine is connected to both the umami-ness of aubergine and to that slippery texture. (This is the same exquisite texture that many children and a very sensitive minority are squeamish about and describe as “slimy.” In Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera, the heroine famously declares, “Very well, I will marry you if you promise not to make me eat eggplant.” Like wine and blue cheese, eggplant is sometimes an acquired taste we must grow into. And then become obsessed.)

The raw fruit is spongy, bitter, and yuck. Roasted, steamed, sauteed, or grilled, eggplant transforms into something almost unguent. It melts in your mouth. It is succulent and slippery. On the tongue, it is soft and carries the flavours and oils that surround it to the whole mouth, melting, then sliding clean away. It feels like foie gras. More often than not, eggplant tastes caramelized. It is absolutely decadent.

Fried Eggplants, Jerusalem Restaurant, 2008, photo by Jamie Bradburn(CC BY 2.0)

Let’s begin with the most basic presentation of aubergine cuisine- rounds or strips of eggplants, sliced, and fried.

A late friend lives on in delicious memories. My friend had many delightful eccentricities, and one was his unusual eating rituals. He could only focus on a limited palette of culinary options at once. There was a whole summer of plain cheese pizzas and iced tea. In other years, if we went for sushi, I ordered a variety packed bento box while he took only several orders of sweet potato maki rolls, hold the wasabi, extra ginger. His favourite destination was Jerusalem on Eglinton West, known as Toronto’s first Middle Eastern restaurant.

The first time we went together, I was salivating under the usual duress of decision making in a menu of opulent variety. Chris ordered sparking water and requested three orders of “fried eggplant,” nothing further, thank you. The platters arrived, looking plain and underwhelming next to my cornucopia of glistening green tabbouleh salad, rich labeneh yogurt, and lamb kafta. But one taste of those eggplants was a conversion experience. They were exquisitely simple with lemon and a melt in your mouth texture that drowned out everything else at the banquet.

It became our custom to catch up over lunch of nothing but water and a table of fried eggplant.

If plain eggplant with oil, salt, and lemon, is so sublime, in harmony with other ingredients, the aubergine is a revelation.

Sichuan Fish Fragrant Eggplant is an umami bomb. The dish name doesn’t sell all western palates, but there are no fish here- just soy sauce, fermented bean pastes, chillis, and garlic. Preparing this stir fry in the wok gets the famously creamy texture. Thai dishes use the long slim pale purple eggplants and often include minced pork. The spicier the better, in my book.

Going from hot to cold, melitzanosalata, or Greek eggplant salad, is one of the very reasons for living. This rustic dip uses roasted eggplant, chopped or more commonly blended, with olive oil, lemon juice, and garlic. Versions of this dip are widely loved across the Levant and Middle East. Made with tahini like hummus, it is most often called babaganoush- which means “spoiled daddy”! The Iranian version is called muttabal and may come garnished with pomegranate seeds.

Roasted Aubergine with Pomegranates, by Stijn Nieuwendijk (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Halved eggplants, roasted, are popular through Iran and the Middle East. They are smothered in tahini, and may have walnuts and pomegranate accents or sauces, sumac, zaatar, and more.

In Serbia and throughout the Balkans, a day without ajvar is unthinkable. The bright red pepper spread is used as a dip, a sauce, and sandwich stuffing- it goes with everything. Recipes with both red peppers and eggplant are extremely popular.

In Turkey, there are literally hundreds of classic, essential eggplant dishes. One is hünkârbeğendi (“the sultan liked it”) and includes eggplant grilled until the skin burns, pureed and sauteed with cubes of lamb. Another, karnıyarık, is eggplant stuffed with black pepper, garlic, onions, tomatoes, parsley and ground meat.

Karnıyarık, Maderibeyza, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Sicily is famous for caponata, a divine relish or stew of fried eggplant, tomatoes, celery, carrots, capers, pine nuts, and olives in an agrodolce (sweet and sour) sauce. And nearly, there is ajloog- Tunisian eggplant and roasted pepper salad, where the two main veggies sing with garlic, lemon, paprika, olive oil and harissa spice. It can be served hot or cold.

In Colombia, a traditional dish is boronia, or mashed eggplants and plantains. It is simple and hearty and satisfying.

And we haven’t even been to Japan, or Nigeria, or Spain, or Indonesia…

In India, where by all our best guesses so far our eggplant was born, there is a very different sleeping beauty story than the one we are familiar with. In an ancient Punjabi fairy tale, we have Baingan Bádsháhzádí, or Princess Eggplant. A poor farmer finds a brinjal plant in the woods and brings it home to grow it by his house. The eggplant girl is so beautiful that they name her Princess Aubergine, even though she is of very humble roots. The wicked queen from the palace hears of the eggplant’s legendary beauty and plots to kill her with black magic. Instead, she kills all of her sons over the eggplant.

After the princess is finally dead, she learns that the place where the eggplant has gone back into the earth is rich with great beauty, and that in fact the girl still came alive in the dark. (Many varieties of nightshade flowers prefer the night or near dawn, hence their name.)

In a rage, the queen goes into the fields to kill her once and for all, but drowns in a serpent filled moat set up by Princess Aubergine and the queen’s own husband. Because she does not love the eggplant, she falls prey to her poisons. The king bade the murderess of his sons good riddance and married the eggplant princess.

The moral of the story? The humble eggplant is always the queen.