Keep cold and drink fresh. These words on many a can of IPA are a motto every craft beer drinker should take to heart. Inverse to what I discussed in my last article on cellaring beer (check that out here), age (and by extension, oxygen) is the true enemy of bright, fresh, hoppy aromatics.

Back when I was younger, I would hunt out the “whales” of craft beer, super hyped, super hopped IPA’s produced in tiny batches, and I would horde cans like I was the dragon Smaug (read The Hobbit). However, every time I cracked one open several months later on some special occasion, I was beyond disappointment. The beer was completely altered, malty and sticky, the lush tropical fruit faded and changed. Now I’ve learned from my lesson, and when I’m at the LCBO with no idea what I want to get, I look past the flashy front labels, and search for the tiny packaging date printed on the can. Fresh is best, and with the 2022 hop harvest looming around the corner, I figured it’s the perfect time to talk about this.

Now this applies to all beers, everything from light lagers to dark beers, but I’ll use the IPA as an example because it’s the most negatively affected. The difference between beers you want to age and beers you don’t, is whether or not it produces a desirable effect. The beers I advised to age are all high alcohol, with intense malt centric character. Age will decrease fresh and citric hop aromas, and increase sweet malty notes, as well as dried fruit character, eventually evolving into some more stale, cardboard aromas if pushed too far. The main culprit here is oxygen, and I found this out the hard way.

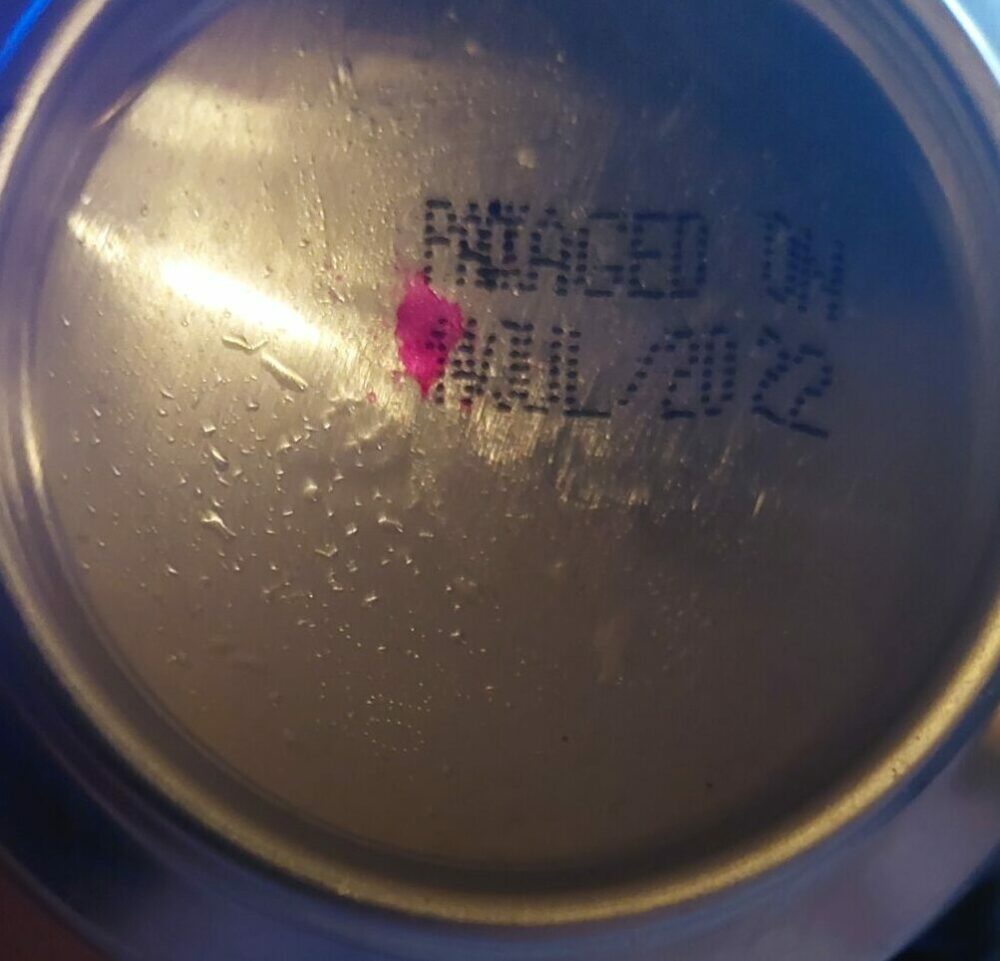

Possibly the most important piece of information on a beer can, often found smudged out or all but indecipherable.

When I started homebrewing my own beer, I was wildly excited for all the things I could make, and I would spend hours planning out complex IPA’s using tons of experimental hops and malts. But they were never how I expected, the hop character was just entirely unlike the explosive aromatics of commercial IPA’s. A big difference is in equipment, and volume. Professional brewers aren’t using a hand siphon and a bucket to transfer, they’re pumping directly from tank to tank, with co2 purges and perfect flow. There are very few opportunities for oxygen to come into contact with the beer. From there, many breweries invest heavily in state of the art canning rigs in order to prevent oxygen contact on the cold side, and it’s exactly after this point most things go wrong.

After all the hard work the brewer puts in to ensure their beer is perfect the moment it hits the shelf, it’s what happens after that point that usually causes the most damage. Improper storage seals the fate of many great beers, and its genuinely unfortunate. I honestly wonder how many IPA’s I’ve drank in my life before I started checking canning dates, beers that just sat in an LCBO for months on end, and when I was inevitability disappointment by the beer I’d write off the breweries abilities, though the condition of the beer might have had nothing to do with them.

Buying fresh beer doesn’t take you out of the woods yet. Temperature can very negatively affect a beer, just like wine. If you go out to pick up beer directly from the brewery the very same day its released, stick it in the back seat of your car, and then to park your car and grab lunch and a movie while your car bakes in the sun, your beer is not going to be the same when you open it. Heat greatly accelerates the chemical reaction that causes oxidization, and that stay in your car (which on an average hot day is something like 43c) will instantly put months of age on your beer in hours.

One phrase that’s always stuck with me in the world of wine is “there are no great wines, only great bottles”, and this is just as true with beers meant to be drank fresh. With hop harvest right around the corner, and fresh hop beers made from 100% fresh-picked whole hops releasing soon, I hope you’ll heed my warnings and not ruin as much great beer as I have.